Multi-faith engagement in a pluralistic culture requires asking questions that invite open conversation rather than handcuff religious self-expression. Take Christian and Jewish discourse for example. It is easy for Christians to ask Christian questions of Jewish people. But I don’t think it is easy for adherents of Judaism to answer them. As one rabbi said to my world religions class years ago, he can’t win when Christians ask him what he thinks of Jesus. If he doesn’t agree with Christians about Jesus, it puts up walls of defense. If he confesses Jesus to appease them, he’s not true to his own tradition. He’s between a rock and a hard place when he is asked to answer this question.

Given how challenging and off-putting Christian questions can be for Jewish people, why don’t we Christians first ask Jewish people and Jewish religious leaders how they would define themselves and their tradition before asking them our burning questions? It’s not that Christian questions lack importance. After all, Jesus–who was Jewish–asked his Jewish disciples, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” (Matthew 16:13; ESV) He also asked them, “But who do you say that I am?” (Matthew 16:15; ESV) Still, if we want to understand how Judaism sees itself, we need to ask representatives of this tradition (and any tradition) questions that foster open conversation and reveal self-understanding rather than handcuff religious self-expression.

Long before we Christians ask questions like “What do you make of Jesus?” we should ask “What do you make of yourselves as Jews or as representatives of Judaism?” Another way to put the matter is to ask Jews what is the most fundamental question they ask themselves. Perhaps the most fundamental question for Jews is how to follow God’s Law. Here’s what Louis Finkelstein says about the matter:

It is impossible to understand Judaism without an appreciation of the place it assigns to the study and practice of the talmudic Law. Doing the Will of God is the primary spiritual concern of the Jew. Therefore, to this day, he must devote considerable time not merely to the mastery of the content of the Talmud, but also to training in its method of reasoning. The study of the Bible and the Talmud is thus far more than a pleasing intellectual exercise, and is itself a means of communion with God. According to some teachers, this study is the highest form of such communion imaginable.[1]

Just as we need to ask Jewish people how they define themselves, and seek to understand the questions they ask of themselves and their tradition, so we need to ask them how they understand Judaism as a “religion.” Nicholas de Lange claims that Judaism is not ultimately a system of beliefs, unlike how many Christians understand Christianity:

The use of the word “religion” to mean primarily a system of beliefs can be fairly said to be derived from a Christian way of looking at Christianity. The comparative study of religions is an academic discipline which has been developed within Christian theology faculties, and it has a tendency to force widely differing phenomena into a kind of strait-jacket cut to a Christian pattern. The problem is not only that other “religions” may have little or nothing to say about questions which are of burning importance for Christianity, but that they may not even see themselves as religions in precisely the way in which Christianity sees itself as a religion. At the heart of Christianity, of Christian self-definition, is a creed, a set of statements to which the Christian is required to assent. To be fair, this is not the only way of looking at Christianity, and there is certainly room for, let us say, a historical or sociological approach. But within the history of Christianity itself a crucial emphasis has been placed on belief as a criterion of Christian identity…. In fact it is fair to say that theology occupies a central role in Christianity which makes it unique among the “religions” of the world.[2]

I would go so far as to argue that Christianity did not see itself historically in the ancient and medieval periods primarily as a set of beliefs, no matter how important, but as a way of life involving faith claims for the cultivation of virtue for human flourishing.[3] Here there would be opportunity for more significant and overlapping conversations between the Christian faith and other faiths than by approaching matters primarily in terms of beliefs and worldviews. Christians must certainly account for orthodoxy (right teaching) in addition to orthopraxy (right practice) and orthopathy (right passion), but never in isolation from them (Refer here to my blog post on the three “orthos”).

With this point in mind, it is important that Christians ask virtuous questions that entail allowing the religious other to define themselves according to their own self-understanding. All-important questions about Jesus, Moses, Muhammad, Buddha, Confucius and other leading religious figures can come later in a multi-faith context. First allow Jewish people and adherents of other traditions to define themselves, and without making comparative religious judgments.

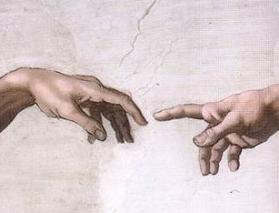

Multi-faith engagement along these lines adheres to the virtuous path of the Golden Rule, which Jesus himself embraced and recognized as the summation of the Hebrew Scriptures: “So whatever you wish that others would do to you, do also to them, for this is the Law and the Prophets” (Matthew 7:12; ESV). And so, if you want adherents of other religions such as Judaism to ask questions that allow you to express your religious self-understanding, ask them questions that provide them that same freedom. It’s only fair.

________________

[1]“The Jewish Religion: Its Beliefs and Practices,” in Louis Finkelstein, ed., The

Jews: Their History, Culture and Religion, 3rd ed. (New York: Harper & Brothers,

1960), 2:1743.

[2]Nicholas de Lange, Judaism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 3.

[3]For an enlightening discussion of the evolution of religion in the Christian West from a way of life to a propositional system of belief, see Peter Harrison, The Territories of Science and Religion (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015).