Have you ever seen Christian voters’ guides? In my Evangelical experience, they often look very red—and I don’t mean red letter for Jesus’ words in the Bible. That’s not to say there aren’t blue versions. No doubt there are equivalents for Democratic leaning churches, no matter the format. Perhaps churches are more diverse today than they were in the 1970’s and 1980’s, perhaps not. I fear, though, that partisan politics easily rules in the church. Here I am reminded of a statement by William Willimon, a United Methodist:

Pat Robertson has become Jesse Jackson. Randall Terry of the Nineties is Bill Coffin of the Sixties. And the average American knows no answer to human longing or moral deviation other than legislation. Again, I ought to know. We played this game before any Religious Right types were invited to the White House. Some time ago I told Jerry Falwell to his face that I had nothing against him except that he talked like a Methodist. A Methodist circa 1960. Jerry was not amused.[1]

In my book Consuming Jesus: Beyond Race and Class Divisions in a Consumer Church, I reflect upon this statement and add:

Both Left and Right have missed out on identifying the church as a distinctive polis or theo-political community that engages culture in view of the cross. For both of them, hope lies in legislation. Going beyond what Willimon says, we might say that they use power politics to promote the agenda of their special-interest groups, and they build walls of separation,not bridges of redemption. They are consumed by the wrong priorities.[2]

While the church must guard against a parochial orientation in which theology is privatized with no bearing on the broader public, nonetheless, the church must realize that it is an embodied witness to Jesus’ kingdom. Jesus did not tell Pilate that his kingdom is indifferent to the world, but that it is not of this world (John 18:36). Jesus’ kingdom intersects, confronts and even affirms at points the established political orders, but always in a manner where he remains Lord. Pilate realized the political connotations and implications bound up with Jesus’ kingship and sided with Caesar and the Roman rule of retribution over redemption (See John 19:1-16).[3]

In our day, one of the ways we fall prey to worldly political forces is in taking up partisan agendas that demonize the other side(s). It’s not that our respective political views for the nation state don’t matter, but they can easily displace our sense of solidarity with Jesus’ larger body, the church.

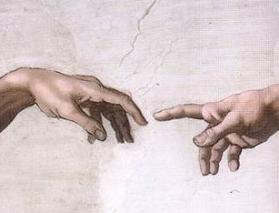

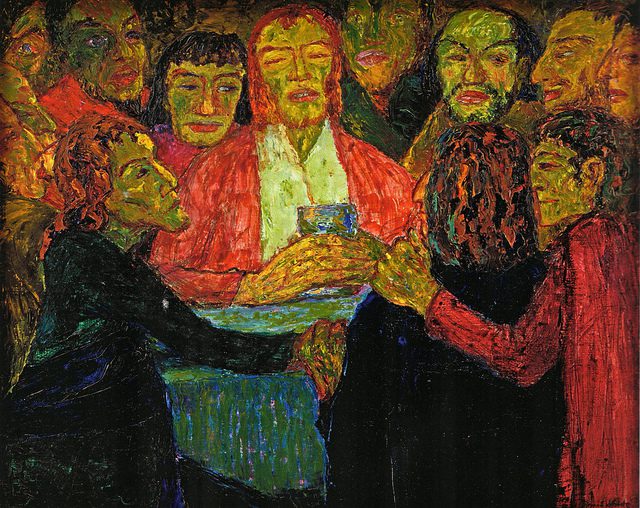

What would conflict resolution involving partisan political tensions look like in our church contexts if we drew inspiration from the Lord’s Table? If we see the Lord’s Table not simply signifying a vertical connection to God, but also involving a horizontal connection to fellow believers, it is hard to demonize and demean those who do not share our political views. It is not that we should discard those views, but we must not discard one another either in the process. Instead of ruling over others, we serve them, as Jesus did (John 13:12-20), which includes listening to their perspective. Moving to and from the Table, we realize our own brokenness, closed-mindedness and closed-heartedness, and how we need to listen more to God and one another in view of our frailty in the pursuit of truth.

No doubt, there were many tensions in Jesus’ inner circle, perhaps involving Simon the Zealot and Matthew the Tax Collector, perhaps even James and John (Matthew 20:20-28). They had different political ambitions and associated with very different political constituencies, but in the end, they submitted those allegiances to Jesus and his kingdom made up of normal and seemingly abnormal types (Matthew 25:31-46), including the orphan, widow and alien in their distress (James 1:27), not all-too-many wise and mighty (1 Corinthians 1:26-31).

Regardless of our political instincts and aspirations, we need to get off our self-righteous high horses and consider others better than ourselves. No better political figure in the history of humanity offers us the solution to our partisan stalemates inside and outside the church than Jesus of Nazareth (Philippians 2:1-11).

______________________

[1]William H. Willimon, “Been There, Preached That: Today’s Conservatives Sound Like Yesterday’s Liberals,” Leadership: A Practical Journal for Church Leaders 16, no. 4 (Fall 1995): 76.

[2]Paul Louis Metzger, Consuming Jesus: Beyond Race and Class Divisions in a Consumer Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), pages 13-14.

[3]Refer to Jürgen Moltmann’s treatment of Jesus’ confrontation of the Roman rule of retribution: The Crucified God: The Cross of Christ as the Foundation and Criticism of Christian Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), pages 136-145. The cross was an instrument used for rebels and traitors, not simply for blasphemy. Jesus was executed as a rebellious blasphemer who opposed the divine rule of Caesar.