“Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and clings to his wife, and they become one flesh” (Gen. 2:24).

It doesn’t say, “a man clings to his husband,” or a “woman clings to his wife.” Right?

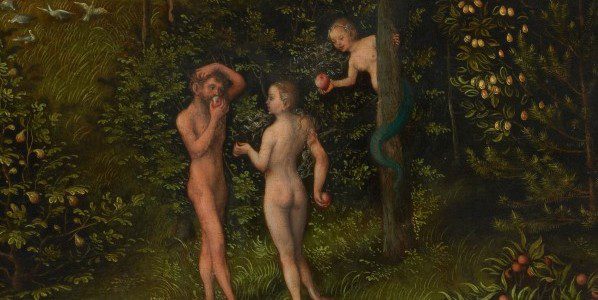

It’s Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve!

People sometimes ask me what books I recommend for evangelicals on the topic of homosexuality in the Bible and church. One I always mention is James Brownson’s Bible, Gender, and Sexuality: Reframing the Church’s Debate on Same-Sex Relationships. I’ll also be saying more about his argument in a post coming next week.

Brownson argues that “one flesh” in Genesis 2:24 should not be taken to exclude same-sex relationships today. This verse is referenced again by Jesus in Matthew 19:5 and Mark 10:8, and also by Paul in Eph. 5:31-32.

The typical, traditionalist interpretation of the verse goes like this (in brief): The Genesis text–and New Testament references to it–assumes that covenantal, loving, and sexual relationships (“become one flesh”) occur between two people of opposite biological sexes: One man and one woman. No allowances are provided–so the traditionalist says–for same sex relationships.

That “one flesh” assumes one man and one woman has become a touchstone for the traditional position on sexuality and of marriage as being exclusively reserved for heterosexual relationships. Not Adam and Steve!

But Brownson makes a crucial point about the difference between what is assumed to be normal by the Bible’s authors and what should be taken as normative (that is, as a morally binding prescription for how we ought to interpret the Bible and apply it ethically today):

Over the course of human history we have encountered questions that take us beyond the assumptions and problems envisioned by the biblical writers themselves, and these new questions and problems have forced us to reread the text and to probe more deeply for answers. The fact that the Bible uses the language of “one flesh to refer to male-female unions normally does not inherently, and of itself, indicate that it views such linkages normatively.

For example, the Bible everywhere assumes that the sun moves around the earth. Yet the “Copernican revolution” forced the church to change its understanding of the normative meaning of statements such as “The world is firmly established; it shall never be moved” (1 Chron. 16:30; Ps. 93:1; 96:30). When we encounter questions and issues not contemplated by the biblical writers, we must not allow the limitations of the experience of the biblical writers to be used to deny the truths that evidently lie before us. The same principles emerge outside the scientific arena, for example, in the moral arena–surrounding the question of the Bible and slavery.

The Bible never envisions the elimination of the practice of slavery in society. The Bible does, of course, call for a “humnization” of the institution of slavery. It appeals to slave owners to treat their slaves justly and compassionately (Eph. 6:9; Col. 4:1) and, in the case of Philemon, it even calls for the freedom of an individual slave (vv. 15-16). But nowhere does the Bible even envision the possibility that slavery itself would or could be banished from society–that is, prior to the return of Christ. Without exception, the Bible urges slaves to obey their masters. These sorts of arguments were made vigorously by slaveholders in the American south against the abolishionists during the middle of the nineteenth century. But the silence of the Bible on issues never envisioned by the Bible (such as the abolition of slavery) is, in and of itself, not a compelling argument. (105)

He then considers the difference in historical context between same-sex unions in the ancient world, which were very different from that which is envisioned in and represented by covenantal, loving, same-sex marriage. So, the biblical world (and biblical authors) simply didn’t know anything like the possibility of same-sex loving relationships as we know them today. (That is, another Copernican Revolution has occurred).

He concludes this section by suggesting a conclusion which is obviously becoming increasingly accepted today, even in the church. What the Bible assumed to be descriptively normative (“one flesh” as the coming together of one man and one woman), due to limitations and the particular shape of its original context, should not be taken as normative for us today. The Bible’s ethical, its underlying moral logic, can be expanded to incorporate other life-giving expressions of relationship today.

But what about loving, committed, long-term, mutual same-sex unions today? Are they inherently incapable of being considered under this rubric? [“one flesh”]? What if such relationships are marked by the recognition of deep kinship obligations, the presence of mutual love, the cultivation of a deep bodily form of communion and self-giving, and the desire for a life of fruitfulness, hospitality, and service to the wider community? Does the fact that Scripture never countenances such relationships mean that they can never exist? Or is it the case that the sexual ethics of Scripture may have a wider applicability than their original scope and focus? (108).

I’ll say more about Brownson’s interpretive approach next week. But in my view what his approach represents is a life-giving way to read Scripture theologically and ethically, bringing the Bible’s to bear on contemporary life.

Stay in the loop! Like/follow Unsystematic Theology on Facebook for more discussion and posts on theology and society