This excerpt from Steve Garber’s book Visions of Vocation is reprinted here with the kind permission of InterVarsity Press. Stay tuned as we continue to occasionally publish excerpts from the book here at Visions of Vocation the blog. And get the book from IVP at this link!

This excerpt from Steve Garber’s book Visions of Vocation is reprinted here with the kind permission of InterVarsity Press. Stay tuned as we continue to occasionally publish excerpts from the book here at Visions of Vocation the blog. And get the book from IVP at this link!

Sometimes questions are asked and you know from their urgency that they must be answered. That is my memory of the weight in George Sanker’s words, “Can we talk this week?” I had given a lecture on the moral meaning of learning, and he was there, eager to take everything in.

It was our first meeting, and I came to see that that was always true of George. At the time, he was teaching high school in Washington, D.C., and one afternoon we met in Union Station, the central thoroughfare of the city. Committed to the calling of teacher, he was well read in the deeper, wider thinking about education but particularly wanted to understand the meaning of character for education. We talked, and kept talking.

As the years passed, his vocation deepened, even as his occupations have taken him to Charlottesville, Virginia, for more schooling, back to Washington to give leadership to a newly opened public charter school, then to Colorado to another school, and finally back to Charlottesville, where he now leads an independent school. Along the way I have been listening to the hope in his heart for a kind of learning that transforms people and their places. In his own memory, it was coming along with his mother as she cared for the home of a wonderful family in Georgetown when he was just a boy that first opened his eyes to learning. Allowed to become a student in the more privileged neighborhood, mixing it up with kids who were expected to excel, he discovered his own gifts, latent as they were. As he grew, not only his mind developed, but his body too, and in his high school years he became a serious athlete. With a college scholarship, he went on for a degree that eventually brought him back to Washington, and to our meeting several years later.

The ways of the heart are complex, and we are wonderfully complex as human beings. Who are we? And how do we become the people that we are? The histories we are born into affect us. The social conditions of our lives affect us. The teachers we have affect us. But it is also true, as Thomas à Kempis once observed in his classic The Imitation of Christ, that “occasions [circumstances] do not make a man frail. Rather they show who he is.” Both sides of the story are true for all of us. A thousand little boys like George did not find their way into adulthood with a Jesuit education and a university degree, but he did. And as he began teaching, he began wondering what makes the difference.

The ways of the heart are complex, and we are wonderfully complex as human beings. Who are we? And how do we become the people that we are? The histories we are born into affect us. The social conditions of our lives affect us. The teachers we have affect us. But it is also true, as Thomas à Kempis once observed in his classic The Imitation of Christ, that “occasions [circumstances] do not make a man frail. Rather they show who he is.” Both sides of the story are true for all of us. A thousand little boys like George did not find their way into adulthood with a Jesuit education and a university degree, but he did. And as he began teaching, he began wondering what makes the difference.

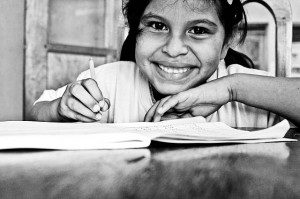

That question brought him to me, and then a few years later it took him to the University of Virginia for graduate study. He wanted to focus on the nexus of sociology, education and philosophy, sure that there was more to learn about learning and about who we are as we learn. That is the vocation that directs his life. One Saturday morning I drove into the city to take part in the opening ceremony of the charter school that George had been hired to lead. I remember thinking about the strangeness and wonder of it all: here was George back in the city of his birth, now opening a school for a host of boys and girls who were a lot like he had been thirty years earlier—so much possibility, so much eagerness, from the littlest kindergartners to the most wizened grandmothers.

And then there was a night several years later when he and I led a Vocare evening for educators throughout the metropolitan area. We call these “conversations about calling,” always pressing into a particular vocation or question. That night we had chosen a monograph by Wendell Berry, The Hidden Wound, where he takes up the far-reaching character of racism in American life. The question we asked was this: tell about this “hidden wound” in your own life as an educator, especially the systemic issues that are often more subtle but are profoundly damaging to the soul of a school. We had newly minted teachers and long-practiced principals, from public schools and private schools, in the city itself and the suburbs as well. The question was not easy, and the answer was not either.

Then came the day that George told me that he and his wife were moving to Colorado to take up the leadership of another school. I sighed, groaning for myself and our city, still wanting to be glad for him and his family. As human beings, the reasons behind the choices we make are always complex, with a host of factors pressing for prominence, but one that seemed to drive George was the opportunity to try again with another school where the question of character formation would be central in the curricular vision. And truth be told, the deep blue skies of Colorado seemed to be calling too.

We make our way through the occupations of life, hoping and hoping that as we do our vocation becomes clearer to us, that over time we will come to know more and more about who we are and what matters to us, and who God is and what matters to him. George is one example of this, but his is only one story of this universal reality. We never know what the future will be, or what the meaning of our choices will turn out to be, until we step in and see, living into our hopes and our dreams.

While colorful Colorado was a gift in many ways, it was not so many years before he was invited to return to Virginia, and to Charlottesville in particular. There were parents who wanted a kind of learning for their community, and they wanted George to help them. The heart of their vision was for an education that taught children to become good people and good students at the same time, so with the sense of longer, deeper home the Sanker family had there in the shadow of Mr. Jefferson’s university, they returned to the East.

In The Abolition of Man, C. S. Lewis’s best-known public-opinion essay, about the state of education in mid-twentieth-century England, he argued that the most important questions of learning were being left out of the curriculum that was shaping British education. “We make men without chests and expect from them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst.” Think of a brilliant hedonist, someone who is incredibly well educated but whose life is marked by selfish egoism; in other words, someone who has a great education but who is without the character required to bring the intellect into healthy relationship to the imagination—which is what virtues are always about, which is what character formation is always about. What was sorely lacking were “chests,” the mediating center where mind and passions could become alive together so that the student would become a whole human being. The stakes were not small for Lewis, or England; he saw the consequence as “the abolition of man.”

In The Abolition of Man, C. S. Lewis’s best-known public-opinion essay, about the state of education in mid-twentieth-century England, he argued that the most important questions of learning were being left out of the curriculum that was shaping British education. “We make men without chests and expect from them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst.” Think of a brilliant hedonist, someone who is incredibly well educated but whose life is marked by selfish egoism; in other words, someone who has a great education but who is without the character required to bring the intellect into healthy relationship to the imagination—which is what virtues are always about, which is what character formation is always about. What was sorely lacking were “chests,” the mediating center where mind and passions could become alive together so that the student would become a whole human being. The stakes were not small for Lewis, or England; he saw the consequence as “the abolition of man.”

A half-century later, Lewis’s critique forms the contours of George’s calling. He lives so that children will become men and women with chests, understanding that the way we educate the next generation will affect the way the world turns out.

Taken from Visions of Vocation by Steven Garber. Copyright (c) 2014 by Steven Garber. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426. www.ivpress.com