The federal budget proposal released this week is in some ways a predictable reflection of the twisted priorities of a global superpower: yet more military spending at the expense of aid to the country’s poorer citizens. And in a further twist, a particular concern about potential cuts to SNAP and Medicaid was expressed in a brief segment on my local NPR station – by a head of veteran housing services.

The federal budget proposal released this week is in some ways a predictable reflection of the twisted priorities of a global superpower: yet more military spending at the expense of aid to the country’s poorer citizens. And in a further twist, a particular concern about potential cuts to SNAP and Medicaid was expressed in a brief segment on my local NPR station – by a head of veteran housing services.

Just let the irony of that sink in. For all the U.S. government is willing to spend on its military, its budgetary priorities hardly reflect the same regard for its soldiers – once it’s done with them.

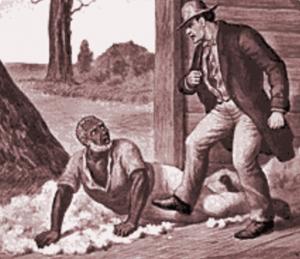

This made me think in a particular way of Simon Legree. Not Simon Legree the cultural cliché – Simon Legree the character. By the time I actually read Uncle Tom’s Cabin, I was surprised to discover that the novel goes a full 30 chapters – two thirds of its length – before introducing its most infamous villain. In contrast to the more conflicted complacency of the slaveholders preceding him, Legree’s coldly utilitarian methods, which he explains to a fellow riverboat passenger, are all the more jolting:

“I don’t go for savin’ niggers. Use up, and buy more’s, my way; – makes you less trouble, and I’m quite sure it comes cheaper in the end.”

Simon elaborates,

“I used to, when I fust begun, have considerable trouble fussin’ with ’em and trying to make ’em hold out, – doctorin’ on ’em up when they’s sick, and givin’ on ’em clothes and blankets, and what not, tryin’ to keep ’em all sort o’ decent and comfortable. Law, ’twasn’t no sort o’ use; I lost money on ’em, and ’twas heaps o’ trouble. Now, you see, I just put ’em straight through, sick or well. When one nigger’s dead, I buy another, and I find it comes cheaper and easier, every way.”

Certainly, the parallel here is not a literal one. But the neglect of veterans, juxtaposed with the politically required adulation of the military (and of course its budget), does point to a certain utilitarian underpinning of the national military mythos. We “support our troops” so vigorously because they are useful to us as the mythic heroes of our nationalistic narrative, and our government (financially and rhetorically) places a high value on them as such – but not as human beings. Once they have been used up for the military’s purposes, they are no longer worth the cost.

When one soldier is dead, or homeless, or suffering post-traumatic stress, we entice another with the promise of a subsidized education and an idealized place in the mythos, until we use them up and repeat the cycle. It makes us less trouble, and we’re quite sure it comes cheaper in the end.