Brad Warner has done a lot of good for Zen in the West. Most practitioners I talk with who are under 40-years-old found their way to Zen through Warner’s books, especially Hardcore Zen.

Warner has cultivated an image of being an irreverent iconoclastic, while ironically embracing orthodox Soto Zen, for example, by exhibiting reverence for Dōgen’s teaching, advocating no-goal zazen, and finding kensho and koan introspection either insignificant or not a part of Soto practice.

Unfortunately, since his first and best-selling Hardcore Zen (2003), Warner has turned a good share of his attention to writing about sex, porn, god, rebirth, vegetarianism and other attention-getting topics.

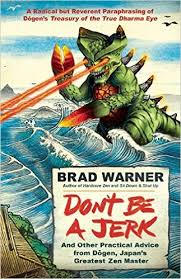

In his new book, Don’t Be A Jerk: And Other Practical Advice from Dōgen, Japan’s Greatest Zen Master (A Radical but Reverent Paraphrasing of Dōgen’s Treasury of the True Dharma Eye), Warner returns to the root of his Zen, his teacher Nishijima Roshi’s perspective on Dōgen’s teaching.

It is a welcome development.

In twenty-six chapters and 300 pages, Warner offers his paraphrases of twenty fascicles of Dōgen’s Shobogenzo, along with analysis of several translations, parsing the original words of Dōgen, and his own commentary. It is an impressive effort, both to present Dōgen in a contemporary, punkish voice and because of the manner in which Warner works – with diligence, integrity, and caution.

And, like other such efforts (i.e., in this regard, a student recently mentioned the rewrites of Shakespeare in modern English), it risks simplifying and missing the richness of the “original” (translated) text.

Yet one of the most frequently asked questions to those of us who teach with Dōgen’s works is “Why is Dōgen so fricking difficult?”

Warner’s Don’t Be A Jerk is an effort to address that question by providing an alternate, modern (irreverent) reading, and careful analysis that offers the reader the opportunity to see for ourselves.

An example? In Dōgen’s fascicle, “Not Doing Evil,” he wrotes, of course, about not doing evil, a tricky concept for those imbued with in the Islamic-Judeo-Christian heritage. So Warner substitutes “jerk” for “evil” and we get, “Even if the whole universe is nothing but a bunch of jerks doing all kinds of jerk-type things, there is still liberation in simply not being a jerk.”

It gets the point across.

But if something is so difficult to understand, why study Dōgen at all?

In Warner’s last chapter, “Dōgen’s Zen in the Twenty-first Century,” he writes, “To me Zen is a communal practice of individual deep inquiry.”

That says it well. For those of us who are engaged in Zen practice as inquiry, Dōgen provides deliciously subtle material to work on and off the cushion. To me it seems especially important in our times to openheartedly entangle ourselves with the ancient teaching, so that we’re not just practicing our contemporary pathology and calling that “Zen.”

I’d like to complement what Warner says about Zen and inquiry by adding that it is also the individual practice of individual insight. And the communal practice of communal insight. And the individual practice of communal insight.

“Communal insight” is especially important for the way we work together in koan introspection. In the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, for instance, we take up insight together, meeting teacher-and-student, face-to-face, even if we’re thousands of miles apart. Dōgen’s teaching works as well for this as any of the koans in the traditional Harada-Yasutani curriculum.

For example, in “Buddha Nature” Dōgen said, “Am I no-buddha-nature when buddha-nature begins aspiring for enlightenment? We immediately ask this, we immediately say it. We immediately make the columns ask it, we immediately ask the columns. We immediately make the buddha nature ask it.”

Instead of just reading this passage and reflecting on it with the frontal lobe, we take it up as a koan, and apply ourselves to it through traditional koan-introspection processes. In this case, the student is invited to “Make the columns ask, ask the columns” – to show it, not talk about. This way of working embodies the teaching in a way that I am convinced Dōgen would wholeheartedly affirm. That’s my opinion.

And speaking of opinions, a word of caution:

When reading Warner (or Dōgen or anybody), it is important to sort the shit from the Shinola. In other words, Warner has a platform here to express his views on the meaning of Zen, koan, zazen, rebirth, and Dōgen’s teaching. He often does that in entertaining ways. However, as Warner himself says, Zen is about inquiry, not belief, so because Warner (or Dōgen or anybody) thinks this or that, the important work is to see it for ourselves in relationship and to “…put such a unitive awareness into practice in the midst of the revaluated world” (Dōgen, “Negotiating the Way”).

Congratulations and thank you, Brad Warner, for a fine Dogen dharma offering.