Editors' Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on Remembering the Dead: Ancestors, Rituals, Relics. Read other perspectives here.

For many years, I served as a hospice chaplain. Although I am deeply shaped by my Lutheran faith, I understood my role as a chaplain to be a part of our society's expression of civil religion where I provided ecumenical resources for the dying and their loved ones and served as a non-anxious presence in the time before and after death. Each year, I helped organize and host a community-wide memorial service for the grieving families of patients served in our hospice program. With the widespread utilization of chaplains in hospitals and hospice programs (the recent Institute of Medicine report Dying in America reports insightfully on the contemporary prevalence as well as ongoing need for spiritual services in healthcare), these types of annual services of remembrance are fairly common.

Recently, I attended a community-wide memorial service that was hosted by the local Catholic hospital. I attended with a widower of the congregation I serve, whose spouse died several months ago. Her funeral had been conducted at our Lutheran congregation soon after her death and her name would be read during our annual "All Saints Day" memorial service on November 1st. Yet when her widower received the invitation to this community-wide service he wanted to attend, and because the invite encouraged bringing your clergyperson, he invited me to come along.

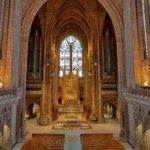

Although I'd visited the clinical floors in this hospital, I had not yet been to the interfaith chapel. As I approached, I could hear the organist playing a quiet, musical prelude. A staff member welcomed me at the entrance and handed me a service bulletin. The lighting was dim and the ambience somber. Groups of two or three sat scattered in the pews. A table of name cards, candles, and a few pictures served as a focal point at the front where an altar would normally be. The bulletin listed seventy-five deaths to remember but it looked like there were only about ten families in attendance. I remembered the times when I had welcomed attendees to the annual memorial service organized by the hospice program in which I served in Louisiana. Like those services, this one was relatively low in attendance. Now as then, I wondered why more people don't attend.

On the one hand, I understand. Each of these deceased persons has already had a funeral or a memorial service and has been buried. Their surviving family members have already done their jobs as defined by Thomas Long and Thomas Lynch in their book The Good Funeral: Death Grief, and the Community of Care:

… to get the dead where they need to go and the living where they need to be…the funeral has the ability to get the living and the dead through this maze of changing statuses. The present becomes the passed away, the formerly here becomes the gone, the wife becomes the widow, and son and daughter suddenly orphaned. (15 and 146)

We have already formally and publically said goodbye to the earthly existence of these loved ones within our own faith communities, mostly Christian, where we acknowledged their death and sought together to make sense of it theologically. In a Christian funeral we have, as Long and Lynch explain, "performed a piece of theater in which we acted out the deepest truths we know about life and death." (119)

Many common elements of a Christian funeral were in this community service, including a reading of Psalm 23 and a singing of the hymn "On Eagle's Wings"—stereotypical, yet still powerful. I wondered what the theology in the sermon would communicate about death and salvation since we were at a Catholic hospital hosting a memorial service that, I presumed, welcomed all faiths. The overall tone was generally Christian, with the priest talking at length about the hope and promise of heaven for all our loved ones. He quoted a hymn we would later sing:

Do not be afraid, I am with you.

I have called you each by name.

Come and follow me, I will bring you home;

I love you and you are mine. (refrain from "You are Mine")

It was appropriately comforting yet not very Catholic, which I admit was a relief to my Lutheran sensibilities, though still far from ecumenical.