As the Civil War ground to an end in early 1865, President Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. It was a gracious meditation. He noted that both the North and South read the same Bible and prayed to the same God. Invoking the mystery of God’s ways, he declared, “The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither have been answered fully. The Almighty has its own purposes.” He cited Matthew 7:1: “But let us judge not that we not be judged.” Worried that Radical Republicans might try to humiliate the South, Lincoln declared that all Americans were guilty. He instructed the nation to reunify “with malice toward none, with charity for all.”

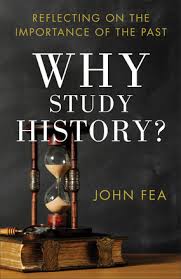

Lincoln was speaking in the context of political crisis. According to historian John Fea, he could just have well been speaking about the possibilities and hazards of studying history. It’s a familiar subject for Fea, a former writer for the Anxious Bench and now a prolific blogger at The Way of Improvement Leads Home (which I read faithfully as a matter of professional development). In Why Study History he contends that historians should emulate Lincoln. They too should withhold judgment, revel in the unknowable mysteries of the past, and empathetically study strange historical characters.

Lincoln was speaking in the context of political crisis. According to historian John Fea, he could just have well been speaking about the possibilities and hazards of studying history. It’s a familiar subject for Fea, a former writer for the Anxious Bench and now a prolific blogger at The Way of Improvement Leads Home (which I read faithfully as a matter of professional development). In Why Study History he contends that historians should emulate Lincoln. They too should withhold judgment, revel in the unknowable mysteries of the past, and empathetically study strange historical characters.

The most striking argument of the book, in my reading, is Fea’s articulation of the limits of historical knowledge. This is not a provocative assertion to the trained historian, but it is for many evangelicals, which appear to be Fea’s target audience. He views evangelicals with ambivalence. The positive spin is that evangelicals are passionate and have a strong activist streak that seeks to better the world. But he also sees certain strains of evangelicalism that practice an ugly triumphalism, an American patriotic jingoism, and a willingness to “use” or “preach” history in partisan ways (be sure to check out his evaluations of Steven Keillor and Eric Metaxas). It is to this sector of evangelicalism, which Fea has encountered to varying levels in the classroom, radio talk shows (be sure to check out the account of Fea’s run-in with Glenn Beck on pages 123-126), and outside speaking engagements, that he issues a powerful admonition.

Fea argues that the past is a foreign country. “It is easy to ignore or dismiss the parts of the past we do not like,” he writes. “Yet all historians must come to grips with its utter strangeness. Too much present-mindedness makes for bad history.” He warns against, for example, the providentialist history of Peter Marshall’s The Light and the Glory, which contends that God has a special destiny for America. Such a conclusion, Fea says, is impossible to prove and fails to consider the “five C’s” of historical thinking: change over time, context, causality, contingency, and complexity. The book works hard to instill a sense of limits, reminding evangelical biblicists of St. Paul’s imagery of seeing through a glass darkly.

It’s true that this book metes out firm correction. But don’t think that this book is a grumpy jeremiad. Why Study History is an enthusiastic declaration of the importance of studying history. Fea meditates on the virtues of historical consciousness. He argues that history has the power to transform individual lives and collective identities. History offers us opportunities to practice—and deepen—Christian virtues of love, hospitality, and compassion for our neighbor. In a chapter entitled “So What Can You Do with a History Major,” Fea offers compelling narratives of fulfilling careers and strong skills sparked by the study of history at the college level. A concluding chapter proposes the creation of a Center for American History and a Civil Society.

This accessible manuscript is peppered with stories from Fea’s teaching and speaking gigs. But it’s also learned, drawing from the best scholars in the evangelical world (Mark Noll, Robert McKenzie) and the broader academy (Sam Wineburg, Peter Novick, Carlo Ginzburg, Gordon Wood). Why Study History, written by an evangelical historian with a growing reputation as a public intellectual, is a terrific primer for undergraduates and should enjoy strong sales in historical methods and philosophy courses at religious colleges.