The standard popular narrative of American religion follows the arrival of the Pilgrims to the New World, where they spread the good news of liberty and capitalism across the continent. God bless America!

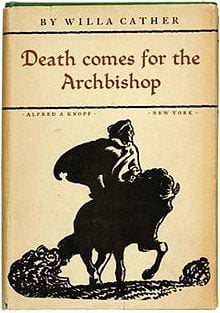

On the surface, Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop seems to reinforce all that. Father Latour, a Catholic priest moving from East to West, intends to missionize the noble savages. He is regal and pious. Indeed, his “bowed head was not that of an ordinary man—it was built for the seat of a fine intelligence. His brow was open, generous, reflective, his features handsome and somewhat severe.” He resembles the mythical George Washington praying at Valley Forge. Cather continues, “He had a kind of courtesy toward himself, toward his beasts, toward the juniper tree before which he knelt, and the God whom he was addressing.”

On the surface, Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop seems to reinforce all that. Father Latour, a Catholic priest moving from East to West, intends to missionize the noble savages. He is regal and pious. Indeed, his “bowed head was not that of an ordinary man—it was built for the seat of a fine intelligence. His brow was open, generous, reflective, his features handsome and somewhat severe.” He resembles the mythical George Washington praying at Valley Forge. Cather continues, “He had a kind of courtesy toward himself, toward his beasts, toward the juniper tree before which he knelt, and the God whom he was addressing.”

Cather, however, complicates the usual narrative. Death Comes for the Archbishop is not a paean to America. Indeed, the United States is not even the main character. Beginning in France and ending in Mexico, the priest shows just how transnational America has always been. Latour’s frames are Native American territory and European empires. The Italian Wars and the election of new popes shape even the wilds of New Mexico. Latour might embrace the new land, but he is nonetheless nostalgic about the Old World, especially his native France, waxing rhapsodic about “towering peaks of his native mountains, the comeliness of the villages, the cleanness of the country-side, the beautiful lines and cloisters of his own college.”

Nor is this a Protestant story. American religion here takes the form of cathedrals, ecclesial hierarchies, miraculous mirages, Marian devotion, venerations of the saints, and celebrations of the Eucharist. It explores many Catholicisms that range from the generosity of Latour to the imperious cruelty of Friar Baltazar to the libertine promiscuity of Padre Martinez. Protestant sensibilities and debates make only cameo appearances.

We also learn much about native religion and culture. The Navajo chants might jangle nerves, but they are also beautiful and transcendent. In Cather’s empathetic telling, the Hopis’ conception of decoration did not extend to the landscape. She writes, “They seemed to have none of the European’s desire to ‘master’ nature, to arrange and re-create. They spent their ingenuity in the other direction; in accommodating themselves to the scene in which they found themselves. This was not so much from indolence, the Bishop thought, as from an inherited caution and respect.” Also consider this description of native hunting techniques: “When they hunted, it was with the same discretion; an Indian hunt was never a slaughter. They ravaged neither the rivers nor the forest, and if they irrigated, they took as little water as would serve their needs. The land and all that it bore they treated with consideration; not attempting to improve it, they never desecrated it.”

Finally, this story of American religion is one of the few non-Mormon stories that takes place in the West. We learn the challenges of building a diocese across vast stretches of land from Sante Fe to Denver. The West as a place becomes alive as Latour plies his religious trade amidst the Gold Rush, Native holocausts, the Mexican American War, the Gadsden Purchase, and the arrival of the train. Cather writes, “As the darkness faded into the grey of a winter morning, he listened for the church bells—and for another sound, that always amused him here; the whistle of a locomotive. Yes, he had come with the buffalo, and he had lived to see railway trains running into Santa Fe. He had accomplished an historic period.”

Death Comes to the Archbishop, as the title implies, does not shy away from the harsh realities of life on the frontier. There was tedium and loneliness. And terrible violence. Hangings became mundane. White settlers herded Natives to reservations. Sometimes they even went “Indian hunting.”

The personal toll in such an extreme environment was profound. Cather writes, “The Bishop rode home to his solitude. He was forty-seven years old, and he had been a missionary in the New World for twenty years—ten of them in New Mexico. If he were a parish priest at home, there would be nephews coming to him for help in their Latin or a bit of pocket-money; nieces to run into his garden and bring their sewing and keep an eye on his housekeeping.”

And yet there is a transcendent quality to Latour’s ministry. Cather writes, “The curtain of the arched doorway had scarcely fallen behind him when that feeling of personal loneliness was gone, and a sense of loss was replaced by a sense of restoration.” Elsewhere: “But when he entered his study, he seemed to come back to reality, to the sense of a Presence awaiting him.” Indeed, God was there in the beginning. Here is Cather describing the bishop’s arrival in the Southwest: “When he opened his eyes again, his glace immediately fell up on one juniper which differed in shape from the others. It was not a thick-growing cone, but a naked, twisted trunk, perhaps ten feet high, and at the top it parted into two lateral, flat-lying branches, with a little crest of green in the centre, just above the cleavage. Living vegetation could not present more faithfully the form of the cross.”

This is precisely the point. Death Comes to the Archbishop, a profoundly mistitled book, is really about life. Indeed, Latour lived a long life, outlasting his parishioners, his colleagues, Kit Carson, and, of course, the Indians. And that life was fully lived. I don’t know that I’ve read a book so sensuous in its description of cherries, apricots, quinces, mahogany, orange trees, oleander blooms, the spare contours of a canyon, and a delectable hare percolating in a sauce. Even on death’s doorstep, Latour could smile and say, “I shall not die of a cold, my son. I shall die having lived.”