Periodically some of the very institutions most responsible for the 24/7-always-on work culture that we inhabit rue that culture, and then give counsel on how to disconnect for a while. Matthew Kitchen, writing recently in the the Wall Street Journal has fresh such advice. Because technology has expanded “the workday’s boundaries until it seamlessly blurs with the rest of civilian life,” Kitchen writes, we need to learn to say no to emails, to switch off our phones. It may be hard to get clear of the madding crowd of co-workers, shooting us a quick note to ask a question or share a spreadsheet.

Lest some among us flinch from claiming the quiet evenings or personal days due to us, the article assures, “actively disengaging from work can help you rest up so you’re more productive during office hours.” Indeed, when we learn how to turn off the always-on work mindset, we might be even better workers and, what is more, look like our work is more important. Kitchen brings us to author Greg McKeown, who observes that “being selective about how we spend our time turns it into a valuable commodity to be traded, ultimately earning you respect and making you more productive when you’re ‘on.’” To help us do this—in Kitchen’s terms, “steal some of my life back”–we may use our functions of Google Calendars or the features of our new iPhone operating system to prevent interruptions. We can even impose apps on ourselves to limit screen time, a kind of child-lock for hardworking adults, that help us regain control of our lives by helping a machine control mask our lack of control.

American religious history offers a range of other strategies taking a break in the work week. Some ways of keeping the Sabbath holy may strike us as more sound than others. Laws in years past have pioneered bans on Sunday mail delivery, or sale of strong drink, or tippling of ice cream sodas. But few earnest believers have topped the Sunday rules put in place by New England Puritans. Especially in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but to varying degrees elsewhere in those northeastern outposts, settlers required themselves by law not to be always on.

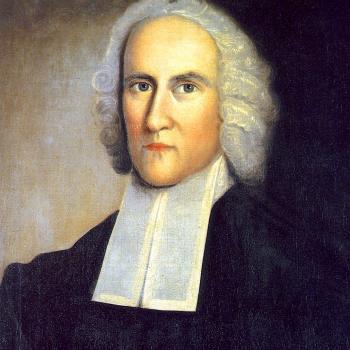

Puritans’ solution to the problem of letting all time be ruled by work are relevant to us in part because they, too, seemed susceptible to a work culture always on. The very embodiment of the Protestant work ethic, settlers of Massachusetts and Connecticut were not only famous for the holy zeal they applied to their labors but for establishing institutions of state, economy, and society to support it. Before leaving England, they had tried—like other Protestants—to reform the calendar, removing the red-letter days and saints’ days, the church-ales and perambulations that had studded every month with days off. They declared all space and time holy, not just the holy-days, which had the effect of making much more time available for work.

Reacting against the Anglican way of doing Sundays in England, New England Puritans put a firm ban on any kind of work on the Sabbath. In his book on the communitarian character of New England work culture, Creating the Commonwealth, Stephen Innes writes, “Hard, productive work for six days was to be followed by one day of almost complete surcease.” By law, everything was shut down on the Sabbath, with rules enforced by enforced by “a potent combination of family, church, and court.” Closed off for the day were “all farming, artisanal, mercantile, and professional work; all domestic labor (including cooking, brewing, sweeping, bedmaking, haircutting, and shaving); all traveling, hunting, drinking, running, and all walking, (even in one’s garden) except ‘reverently to and from meeting.’”

The logic of this system did, however, offer equality in the extension of mandatory rest. Even important people could be fined for breach of Sabbath. The Massachusetts General Court insisted that servants and slaves take rest too. And having everyone be off at the same time avoided the problem of one feeling like a slacker while everyone one else stayed on the clock. The whole town, community, colony was off at the same time. This day off covered not only the kind of output we identify as paid work but household chores too, so mothers were not tasked with cooking and cleaning up after elaborate Sunday dinners. Puritans used technology not to extend work into the day of rest but to block it: hence, the beanpot. Foods like baked beans, which could be left slowly cooking from the night before, let there be dinner without violating rest. Instead of allowing work to seep through all days, the structure of the Puritan week prioritized earnest labor and good planning to confine tasks to six rather than seven days.

Our perception of this kind of Sabbath may be negative, shaped by records left by those who remember hating it as children, a day of enforced doing nothing. Sabbaths, like youth, might be wasted on the young. Even adults might find it gloomy, this working with holy zealous energy all week in all manner of unglamorous jobs, and then sitting still listening to complex sermons for long hours on Sunday before a supper of cold beans. But Puritan logic of the Sabbath does much better than our current advice to guard something important about human life from the insidious grasp of the world of work. At its best, the Journal advice for creating distance from work is mere expedient for the sake of work. You take a break so you can be more productive later. This is exactly backwards. Under these terms, all of our life belongs to the market, and we are given recess only to help us work harder. Instead, the Bay Colony logic of weekdays and sabbathdays reverses the order: one can serve God diligently in a calling Monday through Saturday and fervently in worship on Sunday since all time belongs to God.

Perhaps, though, the Puritan plan was faulty. After all, the upshot of declaring all time holy is to hint that maybe none of it is holy. That is the storied shift from Puritan to Yankee. When Protestantism drops out of the work ethic, nothing may be left besides work. But perhaps it is a helpful signal of something gone wrong with one’s understanding of work, when the logic of it requires “stealing back” one’s life.