Bad things happen to good people. On the face of this, this causes problems for belief systems that insist on some kind of cosmic karma – the idea that there is a supernatural overseer who metes out punishments to the bad and rewards the good.

Theologians turn to several different rationales and justifications to explain these difficulties – often these involve a degree of mental gymnastics and nuances that pass the typical believer by. But what’s rather more interesting to me is how regular people deal with what is, on the face of it, a major challenge to their faith.

Now a team from California State University Los Angeles (namely Heidi Riggio, Joshua Uhalt & Brigitte Matthies) have run a couple of studies to find out.

The studies involved a stories about Chris, a 46-year-old who had suffered a heart attack. In the stories, Chris either took up a healthy lifestyle (exercise, healthy foods, plenty of sleep) or turned to religious behaviours (attending church, worshipping God, prayer). Then Chris either died, or visited the doctor and got the all clear.

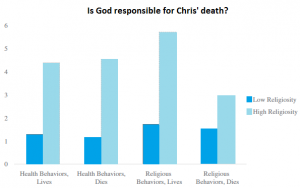

What they found was that their subjects preferred different explanations for Chris’ fate depending on whether or not they were religious.

What they found was that their subjects preferred different explanations for Chris’ fate depending on whether or not they were religious.

Religious individuals, as you might expect, were more likely to say God caused Chris’s outcomes – either living or dying. But they were much more likely to say that God was the cause of Chris living if he used religious behaviours. If Chris used religious behaviours and died, that was nothing to do with God!

They call this the ‘God-serving bias’, and argue that it helps “the maintenance of strongly-held beliefs in the face of contradictory evidence”.

In support of this, they found that religious individuals experienced more joy when Chris was religious and lived (compared with healthy Chris living), and less anger when religious Chris died (compared with healthy Chris, whose death seemed to make religious people particularly angry).

So if God isn’t responsible, is Chris?

The scenario in which Chris was felt to be most responsible for his fate was when he uses religious behaviours but dies. When religious behaviours apparently work and Chris survives, he is seen as less responsible.

But when Chris uses healthy behaviours, it’s the other way around. He’s responsible for his fate if he lives, but not blamed for his death if he dies.

Interestingly, this pattern was seen in both the religious and less religious groups. At first sight that seems strange, but it’s not. As the researchers explain:

While the less religious may attribute Chris’ recovery after religious behaviors to luck or some other cause, the more religious attribute successful use of religious behaviors to the control and causal force of God, as evidenced by their increased attributions to God in this condition.

In other words, the religious defend their world-view by attributing Chris’s survival to god if he lives after using religious behaviours. The non-religious do the same by attributing it to luck!

But both groups seem to have a negative view of using religious behaviours if Chris dies. One thing both groups agree on is that if prays and still dies, he only has himself to blame!

![]() Riggio, H., Uhalt, J., & Matthies, B. (2014). Unanswered Prayers: Religiosity and the God-Serving Bias The Journal of Social Psychology, 154 (6), 491-514 DOI: 10.1080/00224545.2014.953024

Riggio, H., Uhalt, J., & Matthies, B. (2014). Unanswered Prayers: Religiosity and the God-Serving Bias The Journal of Social Psychology, 154 (6), 491-514 DOI: 10.1080/00224545.2014.953024