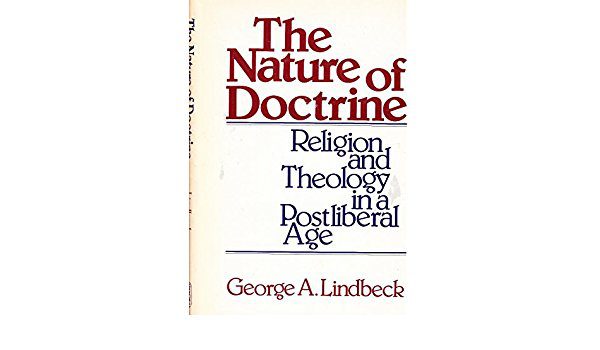

George Lindbeck has died at the age of 94. The Lutheran (ELCA) theologian and Yale professor is considered the father of postliberal theology. This movement is essentially a critique of liberal theology from the standpoint of postmodernism.

George Lindbeck has died at the age of 94. The Lutheran (ELCA) theologian and Yale professor is considered the father of postliberal theology. This movement is essentially a critique of liberal theology from the standpoint of postmodernism.

The liberal theology that dominated mainline Protestantism through much of the 20th century was “modernist.” It professed to be rationalistic and scientific. It worked from a naturalistic worldview. It assumed the tenets of progress, that human beings have moved from primitivism to ever-higher levels of understanding. Which further implied that “old-fashioned” beliefs needed to be changed in accord with “modern thought.”

Thus, it was thought, Christianity needed to adapt to the “modern world” in order to survive. The Bible had to be studied using “scientific” methods, meaning that its supernatural elements had to be discounted and explained in naturalistic terms. In addition to this “higher criticism” of the Bible, which gutted its authority, theological liberals sought to replace otherworldly salvation with improving life in this world, whether by means of the “social gospel” of liberal politics and leftwing utopianism or by replacing spiritual care with the therapy of “modern psychology.” Liberal ecumenism sought to unify the church by jettisoning the archaic doctrines of the various Christian traditions in favor of the new quasi-secularist consensus.

Postmodernism, though, shoots down the major assumptions of modernism. The ideal of objective, rationalistic, scientific certainty is impossible to achieve. There can be no thought apart from language, and language entails a culture, comprised of those who speak that language. Human beings, as well as human thought, are bound by language and culture.

Similarly, postliberal theology critiques the pretensions of theological liberalism. It is absurd for higher Biblical critics to think that they can arrive at “scientific certainty” about the composition and history of a Biblical text from the distance of thousands of years, comprehending an utterly alien language, and working from a radically different worldview. Theologians who dismiss “primitive” teachings are themselves products of a modern Western culture, and their “scientific” claims and naturalistic beliefs are just as culture bound as beliefs of any other society.

But Lindbeck and others went on to adapt the principles of postmodern analysis into a positive way of approaching theology. The church is a culture, an interpreting community with a long, continuous history. The church has a language: its creeds and doctrines and traditions. Also the formative language of God’s Word, which shapes the life and the thought of the church.

To be a Christian is to be a part of this community of faith, internalizing and thinking with the church’s doctrinal and Scriptural language.

Postliberal theologians are also able to contrast the culture and language of the church with that of the world. Thus, they can criticize secular culture and encourage the church to be different, to refuse to conform to the dominant culture.

And yet, to be theologically postliberal is not the same as being theologically conservative. Like other postmodernists, postliberals have problems with absolute truth.

Whereas liberal ecumenism downplays all distinctive doctrines, postliberal ecumenism sees the different denominations as various “interpretative communities,” each with its own integrity. Postliberalism thus takes the different theologies seriously, but it cannot say that one particular church culture and interpretive community is correct and the others are wrong.

The postliberals, in rejecting rationalism also tend to reject doctrinal objectivity. You are shaped by the religion and church tradition you find yourself in. Apologetics has little use.

Scripture gives formative narratives, but not necessarily dogmatic truths, as such. Postliberals do not worry about Biblical inerrancy. They are typically fine with symbolic readings of Genesis. Postliberal theologians can even accept tenets of higher critical Biblical scholarship, but they make them irrelevant to the church’s use of Scripture. If the New Testament is the creation of church tradition rather than historical fact, that’s fine: We are the church and part of that tradition.

Postliberal theologians will discuss the Trinity, the Incarnation, and Justification. That is a great advance over liberalism, which is content to discount such doctrines altogether. Conservatives can often read those discussions with profit. But the postliberals are usually content to explore how the church, or earlier theologians, or various church traditions understand those doctrines, rather than asserting that they are true.

Still, thanks to the postliberals, conservative theologians can now participate in mainstream academic theology in a way that they really couldn’t when liberal modernism was ascendant in the academy. And conservatives are studying at bastions of postliberal theology, such as Yale and Duke, without having to give up their orthodox convictions.

Postliberal theologians such as George Lindbeck deserve credit for overthrowing theological liberalism.

Of course, now we are seeing a postmodern liberalism, which is less interested in theological language and interpretive communities, and more interested in postmodernist politics: The notion that culture and language are all constructions of oppressive power. In this postmodernist social gospel, the church is all about feminism, race, gender, LGBT issues, etc.

To go beyond this postmodernist liberalism, we need to recover truth, which includes overcoming the pervasive gnosticism with a robust theology of creation, reality, nature, and ordinary life. We need to rediscover the truth of God’s Word. That includes the truth of the Incarnation, our redemption, and eternal life, and all that these truths imply.