What inspired yesterday’s post was an article by Karen Prior, whom I’ve known for a long time. She rejects critical race theory, but still maintains that racism is systemic; that is, that “a culture shaped by racist laws, policies and attitudes affects everyone in that culture.”

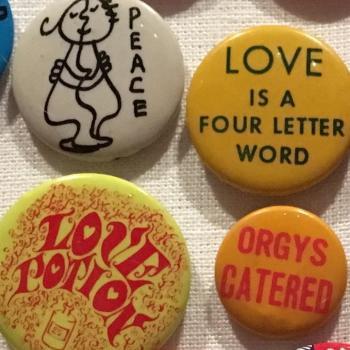

To illustrate what she means, she turns to a different kind of sin that has become systemic: the sexual revolution.

I would like us to reflect on that part of her article. She writes:

The sexual revolution that started in the 1960s — spread through popular culture, enacted by the masses and codified in law — is now as pervasive and inescapable as the popup ads on our computer screens. Almost no home or family or person has been unaffected by it.

Not long after the sexual revolution began, Time magazine, in a 1964 cover story, called it “a revolution of mores and an erosion of morals,” likening the shift to “a big machine” (that) works on its subjects continuously, day and night”:

From innumerable screens and stages, posters and pages, it flashes the larger-than-life-sized images of sex. From countless racks and shelves, it pushes the books which a few years ago were considered pornography. From myriad loudspeakers, it broadcasts the words and rhythms of pop-music erotica. And constantly, over the intellectual Muzak, comes the message that sex will save you and libido make you free.

In other words, the revolution became — and continues to be — systemic. Today, any individual striving to resist the lure of sexual sin has not only his or her own temptations and weaknesses to contend with, but an entire social, cultural and legal system, too.

Good point?

She goes on to cite abortion, which has also become embedded in our culture. “These are not just individual sins, but are entrenched and engrained in our culture. They are systemic.” In fact, she observes the very premise of Christians being engaged in a “culture war” is that moral issues are “cultural”; that is, systemic. “If sexual sin can reshape a culture in our attitudes, laws, policies, values and beliefs in ways we can’t always see or recognize, so can the sin of racism.”

Can we say that sin itself is systemic, that part of what we mean by original sin is that our rebellion against God permeates everything we human beings touch, including the cultures, civilizations, and institutions that we build? That would be why they all, eventually, go wrong, why utopias on either the micro- or the macro- scale are impossible and why “the world,” no less than the flesh and the devil, can so easily tempt us to our ruin.

I think that’s part of it, but a few cautions are in order. We mustn’t lapse into the mindset that “society is to be blame,” rather than the sinful human heart. That’s the error of the Romantic movement, which exalts the purity of the unspoiled Self, and sees “society” as the source of all evils. In this mindset, individuals should throw off the rules and conventions that society imposes upon us all. That perspective, in fact, gave us the Sexual Revolution.

We also have to be careful not to condemn “systems” in their totality just because they have become corrupted by sin. Social structures–such as the family, governments, and communities–are part of what makes us human. They are gifts of God, meant for our flourishing. (Think of Luther’s doctrine of the Estates and the doctrine of vocation.)

In terms of the three estates, the family, the church, and the state may all be corrupted, but we cannot do without any of them. Some today would like to, with some on the Left wanting to abolish the family, some on the Right wanting to abolish the government, and “nones” on both sides wanting to abolish the church. What all three of these estates need–that is, what we need from them–is “reformation.”

Sex is not an evil in itself, but the sexual revolution has made it such by tearing it out of the context of marriage, parenthood, and the family. That is, by removing it from culture. Many of the social sins we decry, while embedded in the culture, are actually anti-cultural. Governments are supposed to help, serve, and protect their citizens, not oppress them.

To be sure, some sins, such as abortion and racism, are evil in themselves. But they too are anti-cultural. Parents are supposed to love and care for their children, not abort them, and to do so undermines the foundation of culture–the family–to its core. Societies are supposed to be made up of individuals who come together to form communities. Mistreating some people because of what race they are is a violation of that communal coming-together that makes culture possible.

So, yes, sin infects systems. They thus need to be “re-formed” around their true purpose and their true nature. Laws that regulate external behavior can help with that, but, ultimately, the underlying sin must be rooted out by the inner transformation wrought by the Gospel.

Illustration: Sexual Revolution Buttons by Jlbrandt, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons