Should we be most concerned with preserving our personal liberties or with promoting the welfare of everyone? Conservatives have lately been debating whether their priority should be the individual or the “common good.”

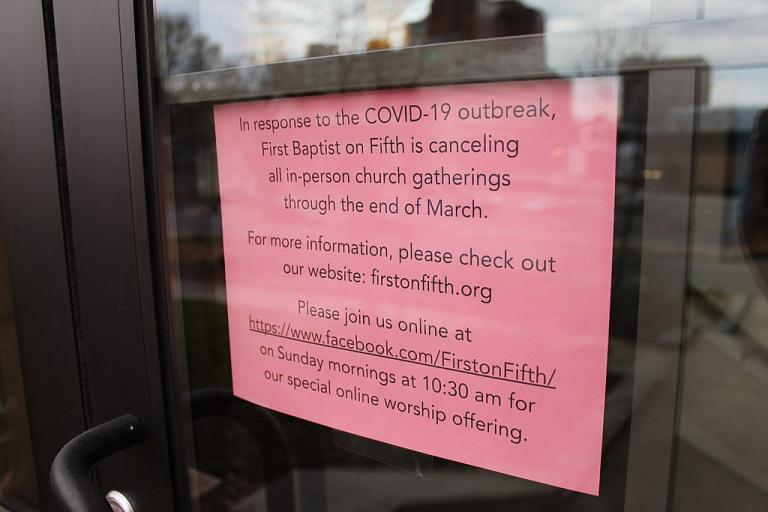

This theoretical discussion has suddenly become very practical with the coronavirus epidemic: To what extent should the government restrict its citizen’s freedoms (to worship, assemble, conduct business, work, travel, etc.) in order to protect the public as a whole from a deadly disease?

The term “common good” is associated with Roman Catholic social thought. In the debates among conservatives, Catholics are often lining up behind that concept, while Protestants are defending the priority of the individual. And yet there is a debate among Catholics too about what the “common good” means. That debate can clarify the issues for Protestants as well.

Catholic theologian C. C. Pecknold summarizes the dispute in First Things. I’ll quote him, suggest how this clears up misconceptions on both sides, and then see how Luther might factor into this debate.

From C. C. Pecknold, False Notions of the Common Good, in First Things:

On one side of the dispute were well-known personalists such as Jacques Maritain, who argued in Scholasticism and Politics that the human person was the fundamental unit of society. “The primacy of the person” provided both a standard for the pursuit of the common good and a powerful check against totalitarian forms of nationalism wreaking havoc on the world. Personalists like Maritain seemed to balance two pillars of Catholic social teaching at once—the dignity of the person and the common good—and won widespread approval. . . .

In 1943, [Charles] De Koninck wrote a powerful essay, “On the Primacy of the Common Good, Against the Personalists,” which sent shock waves through the Catholic world. . . .

What concerned De Koninck most was that personalists refuted modern individualism with nothing more than the primacy of the person, “as if the common good were not the very first principle for which persons must act.” He maintained that this approach doesn’t really combat modern individualism, but rather reinforces it, and makes the common good into something alien to the person. . . .

De Koninck began his 1943 essay with a simple Aristotelian alternative: “The good is what all things desire insofar as they desire their perfection.” The “primacy” should be given not to the person as such but to the good that all persons desire, since this good is what is really good for the person. You and I might love this or that particular good—a smartphone or a car—but these don’t perfect us the way our love for our family, our city, our nation, our church, or even our love for the universe can perfect us. . . .

We have to presuppose that the goods we desire as persons depend on the primacy of the common good of the family, the city, the universe. De Koninck writes, “this conception will certainly be rejected if one thinks of the singular person and his singular good as the primary root, as an ultimate intrinsic end, and consequently as the measure of all intrinsic good in the universe.” . . .

The common good elevates us. While it is good for us to love particular goods, the common good of the family, the political community, or the church calls us to a much greater love of the good than the love we have for particular goods.

[Keep reading. . .]

Notice that the dichotomy here is not the good of the individual vs. the good of the group. Both sides are against “individualism,” though De Koninck thinks “personalism” unwittingly reinforces it. Both sides support the concept of the “common good,” though they differ in what it means.

According to this analysis, the common good is not just what the group wants, nor is it simply what the whole wants. The emphasis in the concept is on “good” and how it is good for all–what is meant by “common”–including the individual.

As I understand the debate, Maritain believes that the common good can be defined as what is good for the person. De Koninck believes that the common good refers to the good that all persons should aspire to.

Though these Catholic thinkers are disagreeing with each other, they would probably agree in condemning Luther, whom they would blame for the rise of “individualism.” To be sure, Luther did stress the individual Christian’s personal faith in Christ, and we Protestants–as well as we Americans–don’t see “individualism” as such a negative term. And yet, Luther can contribute to this debate and can, perhaps, help to resolve it.

In his ethical thought as developed in his doctrine of vocation, Luther emphasizes loving and serving our neighbor. He warns against our tendency to “turn in upon ourselves,” stressing the importance of doing good not just for ourselves–including doing good works as a way to increase our merit so that we can go to Heaven– but that our works should be oriented outside of ourselves, towards helping an actual, concrete human being.

This is not individualism. It is not individual autonomy.

Nor is it pursuing the good as an abstraction or attempting to benefit a collective humanity.

ur neighbor is another person. Not ourselves. We are denying ourselves, even sacrificing ourselves. But we are doing so for a person, someone like yet other than ourselves. This is true “personalism.”

At the same time, we Lutherans have to be struck by the way Prof. Pecknold, in discussing De Koninck’s critique of personalism, keeps referring to the common good in terms of the family, the city/nation/political community, and the church (as well as “the universe”).

These are Luther’s three estates: the household (the family + the economy), the church, and the state. (Luther also speaks of “the common order of Christian love,” the miscellaneous relationships we have, which would surely include “the universe.”) [See Luther’s “Confession of 1528”; Luther’s Works, 37.]

These are the social orders that God created human beings to inhabit. They are the spheres for the various vocations that God calls us to. They are concrete embodiments of the various relationships that we have with our neighbors.

If we think about the “common good” in terms of our love for our family, our country, and our church and what is best for them, the abstract concept is brought down to earth. And when we think of doing good for our specific neighbors in these estates (our spouse and children; our fellow citizens; our congregation), we avoid the problem of directing our ethical obligations to an abstract and impersonal collective, which can never motivate us and which sometimes can be twisted into justifications for tyranny (as in “the greatest good for the greatest number,” or the ironic rationalization of Caiaphas: “It is better for you that one man should die for the people, not that the whole nation should perish” [John 11:50]).

How would we apply Luther’s understanding of the common good, in light of the estates and the love of neighbor, to the epidemic? What would be best for our family and for the economy by which we make our living? What would be best for our church? What would be best for our local community and for our country?

These considerations would surely include how we might love and serve our neighbors by caring for those who are sick and seeking to protect our neighbors from infection. But it would also include loving and serving our neighbors by protecting their livelihoods, their spiritual well-being, and their social relationships. And it would include standing up for their rights.

Photo by Alec Perkins from Hoboken, USA / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) via Wikipedia Commons