LCMS pastor Peter Burfeind has published a terrific article in The Federalist entitled How Our Age’s Melancholy Stems From Loving Ourselves Too Much. The problem, he says, is our particular “cult of self,” which can be traced back through the Middle Ages. And the remedy is that proposed by Martin Luther.

You need to read the whole thing, but I’ll give you an overview. After citing the plague of depression that hits so many people today, as well as other examples of “melancholy” that lead to substance abuse and other problems, Pastor Burfeind takes us on a tour of the Middle Ages and the new ideas about the Self that arose in the 1200’s.

He notes, for example, the influence of technology, namely, the invention of the mirror (!). But that wasn’t the only reason people began concentrating on their individual selves, at the expense of their lives in the objective world. Scholasticism along with Neoplatonism played a role. Then came the “cult of Eros,” found first in the Cathar heretics and then in the troubadours of Romantic Love. Another influence was the mystical millennialist Joachim of Fiore. Then came the Hermeticists, the major figure of whom was Giordano Bruno, also hailed as one of the originators of modern science. Melancholy, said Bruno, was a necessary experience for the self when it realizes that nothing in the world can satisfy its longings. The Hermeticists emphasized vacatio, when the self leaves its body behind, drifting away in its own thoughts and fantasies.

All of this, says Pastor Burfeind, amounted to a recovery of Gnosticism, that ancient heresy that rejects the physical realm in the pursuit of an interior, hidden knowledge, a quest into the self. You can see this mindset today practically everywhere you look–in pop psychology, New Age mysticism, the virtual reality of our information technology, postmodernism, and in the lives of individuals who have never heard of these movements but who are lost on an endless quest for “self-fulfillment” that leads to divorce, instability, isolation, and unhappiness.

No, this isn’t saying that cases of depression are the sufferer’s fault or are tied to sin or a false world view. There are all kinds of reasons for depression, many of them quite justified. Pastor Burfeind’s point is that our culture has a view of self, one that goes far back, that cultivates a sense of alienation from reality and that encourages our proclivity to withdraw from the outside world into ourselves. You don’t have to be depressed to do that–you can be quite cheerful about it–but doing so has negative consequences for everybody, including the culture as a whole.

So how does Luther offer a remedy for this? I’ll let Pastor Burfeind explain:

During Melanchthon’s bouts of depression, Luther would direct him extra nos, or “outside of himself,” toward Christ and everything Christ implied, including his church, the sacraments, and the Scriptures. . . .

Luther would say in rising rates of suicide and depression occur because people “curve in” on themselves, wallowing in a narcissistic pursuit of self-fulfillment, something no different than the mystical Neoplatonic program of the old monks. In a strange way, we have a new monasticism, the isolation of self through media, which can only result in the same pathologies Luther recognized in himself. . . .

Returning to Luther’s counsel to Melanchthon: “Get outside yourself!” For Luther, this meant getting out of the monastery, getting married, and being “other”-directed. His doctrine of vocatio was the answer to vacatio. That is, one’s vocation — as a father, mother, child, employee, pastor, lay person, etc. — directed one’s attention away from self toward neighbor.

Vocatio as the answer to vacatio! Vocation as opposed to escaping the world into oneself! Vocation draws us away from ourselves into involvement with physical reality, so that our love is directed not just to ourselves but to our neighbors!

Pastor Burfeind concludes with these applications:

Our culture suffers from lack of attention to external reality. Younger generations don’t know how to garden, work on cars, engage in basic conversation, or care for others. The trades suffer from the younger generation’s lack of interest, despite the promise of huge incomes. These problems arise because young people mainly engage the world through an internalized, two-dimensional, manufactured reality.

Christians especially should consider the implications of a God who became flesh, who sanctifies the glorious and distinct beings comprising external reality. He, after all, is the “Logos,” or Being, who brought about and secures the “logoi,” or beings, of the created external order. Because of him, our “neighbor” becomes an object of love, not a character in our own psychic dramas. He draws us out of ourselves and into himself, the glorious “other.”

Get outside yourself! For the Christian, reclaim the historic, orthodox, non-gnostic understanding of Christ, and heed the call away from self and the media-manufactured fantasy world. Turn to your neighbors and the external world. Perhaps you’ll also find that joyful draw toward the Logos which, with genuine catechesis, can save your soul.

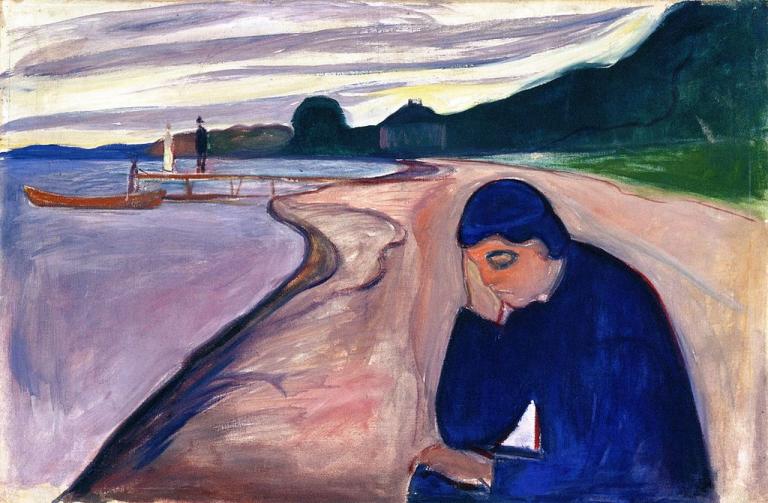

Illustration: “Melancholy” (1893) by Edvard Munch [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons