By Corey Farr

By Corey Farr

“Wait, you’re a virgin?” she said to me.

We hadn’t seen each other since high school. This isn’t exactly the kind of question you’d expect to come up in random small talk with a girl you haven’t seen in eight years and hadn’t been all that close to in the first place, but she had noticed the silver cross-engraved ring on my right hand and asked if I was married. “Nope, that’s the wrong hand,” I said with a laugh. “It’s my purity ring. Remember those? Yeah, I think I’m the only one who’s still got mine.” And so she popped the question, so to speak, “Wait … you’re a virgin?I don’t think I’ve ever even met a virgin!”

I laughed as she said it, but I also was reminded of how very real this was even for people like us who went to Christian school together. Without any judgment or sense of superiority, I explained that I was very much enjoying my life as a single, although I had almost been engaged a couple years prior. At that point she really couldn’t believe that I had made it this long without sex. I mean, almost engaged and you never even got frisky? I shared about how fulfilling I found life in the church and how I really wanted to stick with my commitment to remaining a virgin until if and when I get married.

This passing conversation that I would have easily missed out on if I had chosen to get up and go to the bathroom or just check my phone to avoid the awkward obligatory “catch up” small talk had a profound effect on my friend. Although there were plenty of other pieces to the puzzle, this was one thing that helped spark her desire to return to church and make a new commitment to her faith, which she is still pursuing to this day.

The problem with “purity”

It’s hard to understate the incredible power of the witness of abstinence that single Christians enjoy. “Enjoy” might not be the first word to come to mind for many of us though. Endure, maybe, but not like the endurance of an Olympic marathoner – more like the “enduring” we experience during long lines at the DMV or the grocery store. We’ve discussed “purity” with a vocabulary of pure negation – wait, don’t, stop, be careful, save yourself, flee immorality, and yes, sin – and so no one in the Church truly wants to enjoy our version of “purity.” But there’s another narrative – one that redefines intimacy and reorients our desires around our souls rather than our genitals. And for that reason, it touches the deepest needs of the human heart. It’s a whole lot better than the seemingly arbitrary electric fences our youth pastors put up around everything from holding hands to getting freaky under the sheets.

But if you’re a single reading this, Jesus follower or not, there’s a pretty good chance you are not a virgin. And if you’re in the Church, you’ve probably been told (directly or indirectly) that you have “lost your purity.”

Maybe this hurts deeply. Maybe you don’t care. Maybe you are full of regret, or maybe you’re actually just hoping for the next opportunity to “get some” – if you aren’t already regularly doing so. Maybe you think that you’re just not strong enough to meet the high expectations of purity you were given; or maybe you think those same expectations are a load of primitive, archaic, medieval, puritanical bullcrap. Maybe you were scared with a list of dangers of premarital dangers of sex, like STDs and teen pregnancies, that not only seem far-fetched but made you feel like God’s only reason for asking you to wait until marriage was to avoid these kinds of “punishments.” Or maybe you’re the one who ended up pregnant, whose story was used to scare the others into getting in line while simultaneously shaming you.

We’ve discussed “purity” with a vocabulary of pure negation – wait, don’t, stop, be careful, save yourself, flee immorality, and yes,

sin – and so no one in the Church

truly wants to enjoy our version of “purity.” (

Click to share on Twitter)

Wherever you’re at while reading this, I want to invite you to be right there. I’m not here to preach about abstinence. Instead, I want to focus on casting a vision for the positive narrative of sexuality that has been so lacking. Rather than a how-to guide on “sexual purity,” the goal here is to focus in on the unique set of values that can not only compel us towards abstinence but, more importantly, witness to the Kingdom of God.

Intimacy is different from intercourse

“Anyone can live without sex, but no one can live without intimacy.” This quote from Mike Moore showed up in the first post in this series, and I want to circle look a little more closely at the idea of intimacy.

The word intimacy is related to the Latin word intimus, which means “inmost.” Intimacy is about a deep sense of belonging and love created through transparency, dialogue, and sharing. Although it also refers to physical and sexual relations, this aspect is a lot farther down the list of definitions when you consult the dictionary. Sadly, our culture has hijacked the word, redefining intimacy almost entirely in sexual terms. In fact, to talk about “intimate” friendships with people in the Church, especially when they are of the opposite sex, will often raise some eyebrows. Some might wonder, “What exactly are you guys doing at Bible study?”

We need prophetic voices like Mike Moore to remind us that intimacy is different from intercourse. Mutual love and a sense of belonging are two of our most basic needs, and intimacy is perhaps the best word to describe the way in which they are met. I’m not quite sure why Jesus said that there will be no marriage in heaven (Luke 20:35), but I think that a big part of understanding this teaching has to do with embracing a much deeper understanding of intimacy than what we have been given.

The irony is that a culture so obsessed with sex can be so desperately lacking in real intimacy. And yet, it is actually not ironic at all; the lack of intimacy is preprogrammed into our misunderstanding of the word itself. By setting up sexual fulfillment as the peak of intimacy, it becomes all too easy to completely miss out on this deeper, fuller, more satisfying reality. The intimacy narrative our culture has fed us needs to be replaced with a better one, because until we can do that, we will continue to find our desires shaped by the false narrative, and we will never recognize intimacy outside of intercourse.

God can’t meet all your needs

What does it look like to reorient our sexual desires in light of a more accurate understanding of intimacy when we are constantly receiving messages that sex should be at the top of our priority list? If you’re a single person reading this, you might be skeptical that I’m going to pull out old “find all your needs met in God” trick. Don’t worry – I’m not going there, and I don’t think that ever really works in this area.

Wait, what? Did he just say God can’t meet all my needs? Yes, I did, but let me explain first. We’ve already covered that intimacy – loving and belonging – is one of the most basic human needs. We’re designed for connection. Author Ame Fuhlbruck makes a very helpful distinction, “While spirituality is oriented around our longing to connect with God, sexuality has to do with our longing to connect meaningfully with people.” Although I don’t think this dualistic paradigm is very helpful for defining spirituality, since I believe every part of our life is spiritually significant, Fuhlbruck is making an insightful observation by dividing up human needs for both connection with God and with others in a way that directly parallels the Greatest Commandment of Jesus to love God and others.

Now we need to pause for a moment and look at this word “sexuality.” Some theologians and scholars have distinguished between genital sexuality and social sexuality. Genital sexuality is exactly what it sounds like, and it is pretty much limited to what we have been taught sexuality is. But social sexuality goes far beyond just “messing around.” Social sexuality encompasses all of the affective/emotional relationships in our lives: family, friends, community, etc. Both of these types of sexuality (which can also overlap at times) make up part of the human need for intimate relationships.

You’ve heard the culture’s throwaway line to those struggling with being single: “You need to get laid.” But the truth is that when we experience sexual longing, it may not be actual sex that we need. We may need to be listened to, we may need someone to laugh with, we may need company. These are needs—sexual needs, broadly defined—that the Church should be ready to meet with joy. We should be able to “greet one another with a holy kiss” (or a more culturally acceptable hug) without such physical and relational contact being viewed with suspicion and fear. –

Bronwyn Lea

What makes this distinction so incredibly helpful for singles is that we don’t have commit to living our lives as perpetually sexually unsatisfied. Embracing a holistic sexual narrative, one that realizes that physical acts of sex are only a small piece of what makes up human sexuality, which is itself simply the desire for intimacy with other humans that was hard-wired into us by God.

If sexuality represents the human need for intimacy with other people, then no, God alone cannot fully meet that need. We were designed for community, and God did not create us in such a way that all of our relational needs can be met through an isolated, vacuum-sealed “personal relationship” with him. This is not for a second to deny the goodness or sufficiency of God; it’s actually just to agree with what he has already told us.

All throughout Scripture, we find the importance of community for the people of God. The more we are able to live into this reality with the Jesus followers around us – the more we cultivate our social sexuality – then with time the easier it will become to acknowledge, put in perspective, and deal with our urges for genital sexuality.

This new narrative highlights how important intimate relationships are for meeting our needs and fulfilling our deepest longings. It brings the importance of community to the forefront of our spiritual and social imaginations. This alone will not just magically make our hunger to go to bed with someone else just go away, but it can help us put that hunger in its place.

When we see our sexuality holistically, in other words, when we see that our physical and emotional and spiritual longings are all intimately connected as expressions of a basic need for connection and belonging, then we can prioritize finding and investing in relationships that can help touch that deep need.

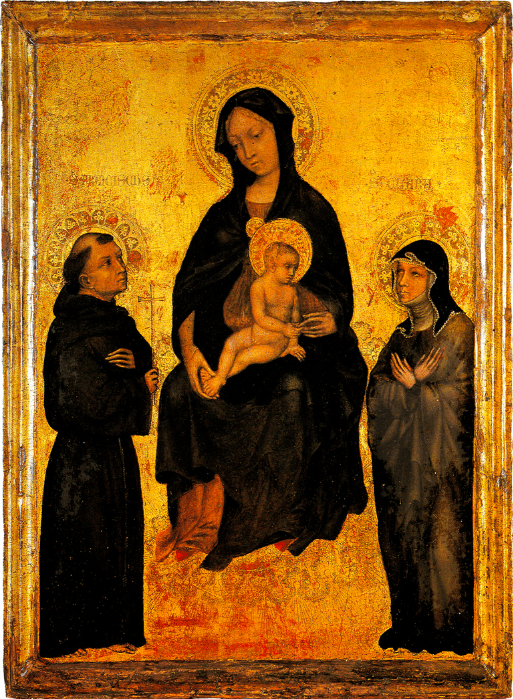

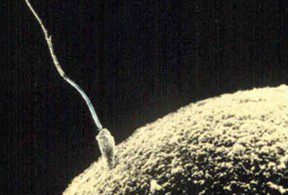

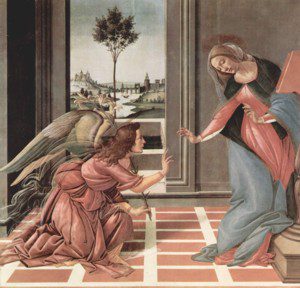

The very idea that a virgin conceived and bore a son raises an eyebrow or two in our secular Western society – both modern and postmodern. At the risk of being a little too earthy – conception in humans requires input from two sources. After all, we all know that an egg from the woman requires the DNA from the sperm provided by a man to make it whole, capable of producing a new individual. One might, perhaps conceive of a clone of some sort using only Mary’s DNA – but this could only make a female, not a male. No Y Chromosome in Mary. If a virgin gave birth to a son it was a truly miraculous conception. The DNA had to come from somewhere. Did God just produce a a unique set of chromosomes to join with Mary’s? Was it Joseph’s DNA? Some other descendant of David? Was this a divine artificial insemination?

The very idea that a virgin conceived and bore a son raises an eyebrow or two in our secular Western society – both modern and postmodern. At the risk of being a little too earthy – conception in humans requires input from two sources. After all, we all know that an egg from the woman requires the DNA from the sperm provided by a man to make it whole, capable of producing a new individual. One might, perhaps conceive of a clone of some sort using only Mary’s DNA – but this could only make a female, not a male. No Y Chromosome in Mary. If a virgin gave birth to a son it was a truly miraculous conception. The DNA had to come from somewhere. Did God just produce a a unique set of chromosomes to join with Mary’s? Was it Joseph’s DNA? Some other descendant of David? Was this a divine artificial insemination? Interaction not Intervention. One of the most important criteria for thinking through the incredible claims in scripture is God’s interaction with his creatures rather than his intervention in his creation. The miracles ring true when they enhance our understanding of the interaction of God with his people in divine self-revelation. The virginal conception is part of the Incarnation, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us”. The magnificent early Christian hymns quoted by Paul in Col 1.15-20 and Phil 2.6-11 catch the essence of this enacted myth as well.

Interaction not Intervention. One of the most important criteria for thinking through the incredible claims in scripture is God’s interaction with his creatures rather than his intervention in his creation. The miracles ring true when they enhance our understanding of the interaction of God with his people in divine self-revelation. The virginal conception is part of the Incarnation, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us”. The magnificent early Christian hymns quoted by Paul in Col 1.15-20 and Phil 2.6-11 catch the essence of this enacted myth as well.