The recent stories of Josh Harris and Marty Sampson, one the well-known author of I Kissed Dating Good-Bye and the other a Hillsong songwriter, have been scrutinized recently. Some had a bit of a databank of others to draw upon for their observations while others had some pastoral experience with folks leaving the faith. There is lots of speculation, so it seems to me, in what is being said.

Some years back I wrote a chapter in a book on this very topic: Finding Faith, Losing Faith. (One chapter in this book was written by Hauna Ondrey, now a professor at North Park Theological Seminary.) My conclusions were based on months of reading depressing stories of “de-conversion” or “apostasy.” It seems that work can be brought to be bear on what is now being said about these two recent departures from the faith. Much of what is being said of late is based on (overly, narrowly) scrutinizing only these two stories and filling in the blanks with some (too much) theoretical speculation.

Some years back I wrote a chapter in a book on this very topic: Finding Faith, Losing Faith. (One chapter in this book was written by Hauna Ondrey, now a professor at North Park Theological Seminary.) My conclusions were based on months of reading depressing stories of “de-conversion” or “apostasy.” It seems that work can be brought to be bear on what is now being said about these two recent departures from the faith. Much of what is being said of late is based on (overly, narrowly) scrutinizing only these two stories and filling in the blanks with some (too much) theoretical speculation.

My conclusion at the end of my study is that a person apostasizes or leaves the faith to find independence. This autonomy can be intellectual, psychological, or moral (or behavioral) or more than one or all of them. My study leads me to believe we should be looking through the statements of someone like Marty Sampson to what he wants to do, how he wants to behave, to whom he wants to answer. He’s looking for independence for something.

I’ve grabbed a few paragraphs from my chapter in what follows:

Theoretically speaking, all conversions are apostasies and all apostasies are therefore conversions. Everyone who converts leaves a former faith, even if that faith is ill-defined. Everyone who leaves the orthodox Christian faith converts to a different faith, even if that new faith is as ill-defined as a kind of agnosticism or personal theism or even gentler forms of atheism. Those who study conversions often observe that a conversion to something means a conversion from something else, but rarely does the observation work itself into the fabric of one’s study of conversions themselves. One rare exception is the fine study of John Barbour, who specializes in studying autobiographies.

In his study, Versions of Deconversion, Barbour observes that those who tell their own stories of conversion also reflect on their own past through four lenses:

they doubt or deny the truth of the previous system of beliefs;

they criticize the morality of the former life;

they express emotional upheaval upon leaving a former faith; and

they speak of being rejected by their former community.

Barbour studies some of the most important “autobiographers” in the history of the Church, including Augustine, John Bunyan, and John Henry Newman. These people not only had great skills in analyzing their own conscience, but their own stories have shaped how Christians have learned to tell an acceptable story of conversion. To study these tree figures is study how Christians have learned to tell a conversion story. And one element of this story is the need to explain the inadequacy of their former life and even anyone associated with it. This study will reverse the typical Christian story to study those who have left the faith, those who have committed what the historic faith calls “apostasy.”

There is no historic profile for someone who leaves orthodoxy or, to use a clinical and historical term, who commits apostasy by abandoning orthodoxy. Some of those we have studied were nurtured into the faith in committed Christian homes (like Christine Wicker) while others experienced dramatic conversions to the faith (like Templeton and Loftus). Each, for a variety of reasons, encountered issues and ideas and experiences that simply shook the faith beyond stability. In essence, those who leave the faith discover a profound, deep-seated, and existentially unnerving intellectual incoherence to the Christian faith. The faith that once held their life together, gave it meaning, and provided direction simply no longer makes sense. For such persons, the whole of life has to be reconstructed from the bottom up.

Not all who experience this intellectual incoherence abandon their faith permanently. Timothy Larsen, a professor at Wheaton College, has detailed the stories of seven intellectuals who not only endured a crisis of faith that shook their faith but who also, once on the other side of the fence, experienced another crisis of doubt that led them back to the orthodox faith. His book, Crisis of Doubt, remains an enduring reminder that walking away can be followed up eventually by returning home.

What were the issues and ideas and experiences that precipitated their “crisis,” their walking away, and their quest for a new and different kind of life, one no longer related to that original faith?

Scripture in tension with what one believes Scripture is/ought to be

Science and faith in a war with one another

Christian hypocrisy

Hell as taught: eternal conscious punishment/torture

The God of the Bible (Old Testament usually)

In my study, one and nearly always a combination of the above five major elements forms the core of a crisis in the viability of one’s orthodox Christian faith. Because humans are complex and because our decisions are made in the crucible of life with all its connections and because with nearly every person I have studied there is more involved than one issue, when a scholar like Bart Ehrman seems to reduce his crisis to the discovery that the text of the New Testament cannot be determined with certainty, someone who studies conversions is left wondering what else was involved in that decision. After discovering that Abiathar in Mark 2 was a mistake, Ehrman says this of his own mind: “Once I made that admission [that the Bible could be wrong], the floodgates opened.” From there Ehrman charts the devolution of his own orthodox faith. Such, indeed, was his crisis. The result of a crisis like this for those we have studied is a collapse of their own personal faith in Jesus Christ and all that entails, including ostracism from one’s faith community and the reconstruction of a new world of meaning.

Even if the stories of those who leave the faith do not emphasize the benefits one finds or the newly-found intellectual coherence on the other side, intellectual coherence is the immediate and most sought-after desire. Perhaps the best evidence for this is the animus one finds in the constant diatribes and arguments such persons express against Christianity. Many of us have seen this in Richard Dawkins, author of the fiery book The God Delusion. It is my contention that what drives a Charles Templeton to write out in white-hot prose his railing away against Christianity in his Farewell to God, or John Loftus to write an entire book detailing his credentials and arguments with his former faith, Why I Rejected Christianity, or Harry McCall to resort to caricature, or Dan Barker finding a need to tell that story in Losing Faith in Faith, is the same: the intellectual incoherence they discovered in Christianity led them especially to debunk Christianity and attempt, so far as they are possible, to construct intellectual coherence and personal meaning on the other side. Another way of putting this is to suggest that those who leave the faith feel like jilted lovers or even betrayed by the one they loved. There is a need for anti-rhetoric, a need to make their problems with the their past a matter of public record.

In the end, to circle back to Thomas Paine, the advocate for those who leave the faith is reason, autonomous, independent, freethinking reason. “I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.”

Regardless of who the person is and where they came from, in the end those who have walked away from the faith have come to terms with an inner reality: they have to make up their own mind and live with the results.

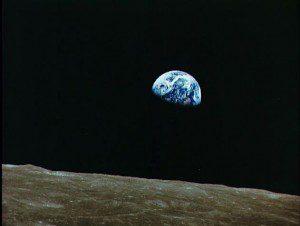

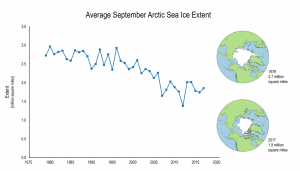

We have no excuses. We can’t plead ignorance and we can’t retreat between the smokescreen of caring for people first not the environment. Nor can we retreat behind the smokescreen of false humility, as though humans can’t actually have an effect on God’s world. Clearly God allows humans to mess things up royally. No

We have no excuses. We can’t plead ignorance and we can’t retreat between the smokescreen of caring for people first not the environment. Nor can we retreat behind the smokescreen of false humility, as though humans can’t actually have an effect on God’s world. Clearly God allows humans to mess things up royally. No  What now? Moo and White may overemphasize a biblical mandate for “creation care,” but their approach is generally helpful and clearly debunks the notion that this world is to be viewed as a temporary consumable. Many others go much further with a biblical call for “creation care”, but this really isn’t warranted. I don’t think it is an issue that the Bible speaks to directly in any fashion. It simply wasn’t on the radar screen of the authors and God didn’t insert these 21st century concerns into their minds and thoughts. But the fundamental message of scripture certainly applies. Repent of sin (aware of how ingrained our ability for self deception is), love God, follow Christ, love others.

What now? Moo and White may overemphasize a biblical mandate for “creation care,” but their approach is generally helpful and clearly debunks the notion that this world is to be viewed as a temporary consumable. Many others go much further with a biblical call for “creation care”, but this really isn’t warranted. I don’t think it is an issue that the Bible speaks to directly in any fashion. It simply wasn’t on the radar screen of the authors and God didn’t insert these 21st century concerns into their minds and thoughts. But the fundamental message of scripture certainly applies. Repent of sin (aware of how ingrained our ability for self deception is), love God, follow Christ, love others.

The heavens will disappear with a roar. Verse 12 talks about the destruction of the heavens by fire. However, this doesn’t refer to the disappearance of the universe as we know it, the stars, planetary systems, and galaxies revealed by telescopes with sensitive cameras studied by astronomers and astrophysicists. Neither the author nor his audience knew anything of this. Rather, the picture in their minds was of the heavens as the realm of God and his angels.

The heavens will disappear with a roar. Verse 12 talks about the destruction of the heavens by fire. However, this doesn’t refer to the disappearance of the universe as we know it, the stars, planetary systems, and galaxies revealed by telescopes with sensitive cameras studied by astronomers and astrophysicists. Neither the author nor his audience knew anything of this. Rather, the picture in their minds was of the heavens as the realm of God and his angels.

And now to Paul. Moo and White then turn to Paul in 1 Cor. 15. The good news is the story of Jesus, the Messiah; his life, death, and resurrection. “That Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures.”(1 Co 15:3-4) Whenever Paul refers to the gospel he also refers back to the Scripture – i.e. the Old Testament.

And now to Paul. Moo and White then turn to Paul in 1 Cor. 15. The good news is the story of Jesus, the Messiah; his life, death, and resurrection. “That Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures.”(1 Co 15:3-4) Whenever Paul refers to the gospel he also refers back to the Scripture – i.e. the Old Testament.

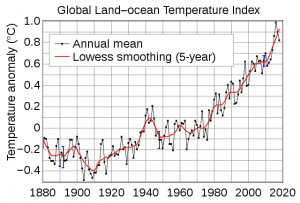

Moo and White also include a plot of three different global average temperature records created independently. The NASA average (one of their three but updated through this year) is plotted to the right – image from wikipedia. The other two follow the same trend.

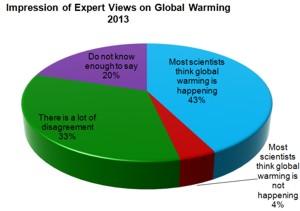

Moo and White also include a plot of three different global average temperature records created independently. The NASA average (one of their three but updated through this year) is plotted to the right – image from wikipedia. The other two follow the same trend. Why is there so much skepticism? Moo and White point to six contributing factors. The first is that climate is a long-term average phenomenon, yet we experience weather on a day-to-day and year-to-year basis. It is hard for the average person to grasp the changes or the potential consequences. The media also plays a role by giving equal time to opposite sides of the debate. Open discussion is good, and should happen in the media, but because the format tends to feature one supporter and one skeptic the audience comes away with the impression that there is a great deal of disagreement in the scientific community in general and among climate scientists in particular. The pie chart illustrates the public impression (data from

Why is there so much skepticism? Moo and White point to six contributing factors. The first is that climate is a long-term average phenomenon, yet we experience weather on a day-to-day and year-to-year basis. It is hard for the average person to grasp the changes or the potential consequences. The media also plays a role by giving equal time to opposite sides of the debate. Open discussion is good, and should happen in the media, but because the format tends to feature one supporter and one skeptic the audience comes away with the impression that there is a great deal of disagreement in the scientific community in general and among climate scientists in particular. The pie chart illustrates the public impression (data from

Throughout his book Moberly has used passages from Aeneid 1 and Daniel 7 as case studies to discuss the privileging of the Bible. In the Aeneid, Jupiter bestows on Rome unending dominion over the world, “On them I set no limits, space or time: I have granted them power, empire without end” and establishes a descendant of Aeneas to rule the Roman empire and establish peace.

Throughout his book Moberly has used passages from Aeneid 1 and Daniel 7 as case studies to discuss the privileging of the Bible. In the Aeneid, Jupiter bestows on Rome unending dominion over the world, “On them I set no limits, space or time: I have granted them power, empire without end” and establishes a descendant of Aeneas to rule the Roman empire and establish peace. Daniel 7 describes a vision where one like a “son of man” comes before the Ancient of Days and is given dominion and glory and kingship – an everlasting dominion that shall never be destroyed. The Ancient of Days is understood to be Israel’s God. On the surface Aenied 1 and Daniel 7 are similar accounts.

Daniel 7 describes a vision where one like a “son of man” comes before the Ancient of Days and is given dominion and glory and kingship – an everlasting dominion that shall never be destroyed. The Ancient of Days is understood to be Israel’s God. On the surface Aenied 1 and Daniel 7 are similar accounts. In Matthew 4 we read the well known story of the temptation of Jesus. The devil offers Jesus dominion if he will only worship him and Jesus replies “Away with you, Satan! For it is written: ‘Worship the Lord your God, and serve him only’.” Power and authority is not given by Satan or for the good of the one to whom it is given. We see this again on the cross and in the events leading up to it. Moberly highlights two passages. Matthew 16 where Peter recognizes Jesus as the Messiah, but then rebukes Jesus for saying that he, as God’s Messiah, must suffer. Peter’s response is very human “Never, Lord! This shall never happen to you!” Jesus turns to Peter, “Get behind me, Satan! You are a stumbling block to me; you do not have in mind the concerns of God, but merely human concerns.” But he has a word for the disciples (and us) from this interchange: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it.“

In Matthew 4 we read the well known story of the temptation of Jesus. The devil offers Jesus dominion if he will only worship him and Jesus replies “Away with you, Satan! For it is written: ‘Worship the Lord your God, and serve him only’.” Power and authority is not given by Satan or for the good of the one to whom it is given. We see this again on the cross and in the events leading up to it. Moberly highlights two passages. Matthew 16 where Peter recognizes Jesus as the Messiah, but then rebukes Jesus for saying that he, as God’s Messiah, must suffer. Peter’s response is very human “Never, Lord! This shall never happen to you!” Jesus turns to Peter, “Get behind me, Satan! You are a stumbling block to me; you do not have in mind the concerns of God, but merely human concerns.” But he has a word for the disciples (and us) from this interchange: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it.“