By Noah Lawrence

For the first time, I almost couldn’t find a prayer book. That is how many people came to my synagogue for the first Shabbat after the shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue.

I knew something was different the instant I walked inside the wooden-walled, linoleum-floored, home-like little multipurpose room that houses the Beis Community (“beis” means “home” and is here a pun on the English “base”), a liberal-Orthodox synagogue and hub especially frequented by millennials in Washington Heights, New York City.

I wasn’t later than usual, but usually, I walk in as the introductory songs conclude, followed by the summons to pray, the Barekhu(“Let us bless”). This time when I walked in, the congregation was already well along in the main series of services, as that day’s lay leader chanted the blessings of the Amidah(or “Standing,” the core worship service) and the congregation responded “Amen.”

More people came than usual — and they came on time.

Everything about that Shabbat was intensified. My synagogue’s practice is that the rabbi doesn’t give one sermon; various laypeople give mini-sermons. Usually, anyone can speak spontaneously. This time, the rabbi announced that all but one slot had been requested beforehand.

Most speakers talked about the tragedy, offering words of loss and hope. One speaker simply discussed the weekly Torah portion, an act that in its own eloquently unspoken way addressed the tragedy, by insisting that hate not stop normal life, and spiritual life, from thriving.

Sometimes, the day’s intensity manifested through changed routine. After the Torah reading came the usual ceremony in which one person — me this time — raises the Torah scroll, after which someone else dresses the Torah in its velvet covering. This time, the rabbi said to the two of us: “May you raise the Torah high, so all can see it. And may you wrap the Torah tight, to keep it safe.”

Sometimes, the intensity manifested precisely through routine. As we sang certain of the regular prayers — the prayer for the sick; “Tree of Life,” the Pittsburgh synagogue’s namesake hymn — this time, you could hear and feel both the pain of fresh loss and the comfort of the familiar, the dependable sameness of liturgy and the difference of what it meant to us this time, melded in swelling emotion. It was as if all the other instances when we had sung these prayers were to prepare for this time.

My synagogue was no outlier. The American Jewish Committee reports: “From New York to New Zealand and from Utah to the UK, millions of Jews and people of all faiths pledged to #ShowUpForShabbat Nov. 2 – 3 in solidarity with Pittsburgh’s Jewish community, sending a resounding message that love triumphs over hate.”

***

American Jewry and indeed the country are experiencing a sea change. On the morning of the first Shabbat Eve after the shooting, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s headlineread: “Yitgadal v’yitgadash sh’mei rabah,” in Hebrew letters. The sub-headline: “These are the first words of the Jewish mourners’ prayer, ‘Magnified and sanctified be Your name…’”

I read that headline and glowed with the togetherness and generosity of spirit that it offered. A major American city’s newspaper of record was, literally, speaking my language. Indeed, many publications used the Hebrew word “Shabbat” in place of the English “Sabbath.”

The press was no outlier. “Iranian raises $1 million for Tree of Life, gets showered with offers of Steelers, Penguins tickets,” one headline said. “Pittsburgh Steelers Player Honors Synagogue Attack Victims With ‘Stronger Than Hate’ Cleats…with the Star of David,” read another — referring to the quarterback, Ben Roethlisberger. “Anguished by ‘Spiral of Hate,’ Charleston Pastor and Pittsburgh Rabbi Grieve as One” — the picture showed them embracing.

Before a UVA-Pitt football game, the UVA Alumni Twitter account tweeted, “Stop by our tailgate…[to] sign a card that we will send to the Tree of Life synagogue.” Even Bank of America offered an ATM screen message: “We stand with Pittsburgh,” adding, “Offering our sincerest condolences and heartfelt support to all of those affected,” with a picture of a candle.

When statements of empathy mention Jews and the Tree of Life synagogue, I feel seen as a Jew, empathized with as a Jew. I feel that the shooter’s attack on Jews because they were Jews is acknowledged as such (the opposite of the counter-motto, “all lives matter”).

When statements mention only Pittsburgh, one might see them as whitewashing. I see them differently. Given that empathy is their foundation, I see such statements as either reflecting a misplaced political correctness (i.e. a fear of mentioning ethno-religious background whatever the reason), or precisely evoking America’s embrace of Jews, such that an attack on Pittsburgh’s Jews is an attack on all of Pittsburgh. (By contrast, I recall a French newspaper that, after an anti-Semitic attack in France, reported that x many Jews and y many Frenchmen were killed.)

I posted on Facebook about the shooting. People from all backgrounds — from people with whom I am currently in touch to long-lost acquaintances — liked and commented on my words. I am truly appreciative. Each one offered me one more electronic flag’s worth of solidarity.

***

“Something is happening here,” as Bob Dylan and Stephen Stills sang in the 1960s. How can we understand it?

The welcome extended by America’s broader culture of a Jewish presence — and, intertwined therein, Jewish self-confidence and flourishing — has evolved through several eras. First was the Cary Grant era: you can be part of the broader culture, but only if you’re closeted as a Jew. Then came the Dustin Hoffman era: you can be part of the broader culture un-closeted—you can even bring a bit of Jewish spirit, as Hoffman did to his pensive, wilderness-wandering character in The Graduate—but don’t be too in-depth about it.

Then came the Prince of Egyptera. You can finally experience public, overt, in-depth Jewish richness, complete with singing in Hebrew. But you have to do it yourself and, to a significant degree, alone. (The Prince of Egypt was, significantly, not from Disney, but from then-upstart DreamWorks, and the brainchild of Jeffrey Katzenberg and Steven Spielberg.) And you must muster the guts to engage Jewishly despite a remaining sense that being Jewish isn’t as normal as being a white Christian — that being Jewish is something to be more than a little embarrassed about — that all Americans are normal but some are more normal than others.

The post-Pittsburgh uplift presents the opportunity for an entirely new era in the history of America’s covenant with Jews, and American Jews’ covenant with ourselves. From Hebrew letters on a front page to a Star of David on a quarterback’s cleats, the level of ally-ship and inter-communal fellowship that Jewish-Americans are experiencing today is unprecedented. It offers a wholly new level of realization of a marvelous promise: that we — that any group — can be numerically a minority yet equally normal. The blossoming of #ShowUpForShabbat represents a high-water mark, too, for American Jews’ enthusiasm for Jewish tradition and self-confidence about it. If a sizable portion of this reality endures past the initial post-tragedy moment, it will be something truly new under the sun.

Which, then, does the Pittsburgh story represent: the undying dark side of Jewish history, even here in America, or the reality of this country’s exceptional embrace of Jews? The answer is both — and both to novel degrees — in a poignant simultaneity. After Pittsburgh, and after Charlottesville and other recent troubles leading up to Pittsburgh, one cannot help but conclude that America has not offered a Francis Fukuyama-esque end of Jewish history, despite the hope that it would (as modern Israel, too, has not, despite the hope.) But for millions of all backgrounds, America as a country where all are at home and no one is a guest — American exceptionalism in the best sense — is real, if painfully incomplete. Jews are included in this — more today than ever before — and now is the time to double down.

***

How else can we understand what is happening here? Stories can help us. In recent days, I have been thinking of a few Torah stories especially.

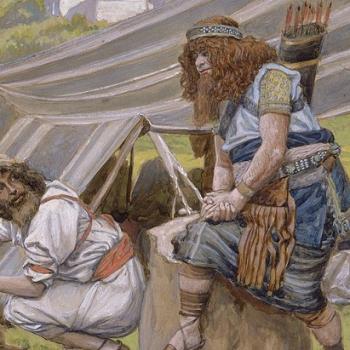

The first is that of Amalek, the nation that attacked the Israelites as newly-freed ex-slaves in the desert (Exodus 17). The Torah specifies, in delayed exposition designed to stun the reader (Deuteronomy 25), that Amalek attacks from the rear, striking first those who were struggling to keep up. Some of the story’s takeaways have evolved over time — the Bible vows wiping out Amalek in response; by later antiquity, the rabbis of the Talmud found a way to void this dangerous provision, per the overall value of inclusivity (Babylonian Talmud, Volume Berakhot [Blessings] 28a). Yet, the story’s core is best understood as a clarion condemnation of killing Jews or others based on who they are, especially the vulnerable.

Another story is that of Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law (Exodus 18). Like Amalek, Jethro is not Israelite — he is Midian’s priest — yet Jethro comes not to attack, but to aid. Jethro blesses the God to whom the Israelites pray, though his own beliefs differ. He offers empathy for Israel’s suffering, and celebrates Israel’s liberation. He breaks bread with the Israelite elders. And he offers Moses his wisest, most caring advice, suggesting that Moses create a court system rather than exhaust himself as a one-man judiciary.

The most haunting quality in these stories is their sequence: Amalek, followed immediately by Jethro, then by the revelation at Mount Sinai (beginning in Exodus 19). Rabbis and Jewish scholars throughout the ages, from Abraham ibn Ezra to Umberto Cassuto to our own era’s Robert Alter, have commented that by juxtaposing Amalek and Jethro, the Torah shows that when difference exists, people can act per either model — a warning to those hoping for only Jethros, but a balm amid fear of only Amaleks.

And the fact that the Jethro story surges toward Sinai indicates that, while one might see opening up to others and being deeply ourselves as necessarily a contradiction, not so. Jewish history’s most particularistic moment is preceded by a moment of vivid universalism.

This time in American history is a time of Amalek, Jethro, and Sinai. Like Amalek, the Pittsburgh shooter wantonly killed Jews. Like Amalek, he targeted from the rear, killing mostly elderly congregants; all but two were 65 or older. The country and indeed the world are experiencing an Amalek-like resurgence — from African-Americans at a Kentucky grocery store to women at a Florida yoga studio.

But like Jethro, people of varied backgrounds are coming to the aid of Jewish-Americans and others. In story after story, people are testifying that different people can indeed share bread and empathy.

And as at Sinai, American Jews are coming out to live Jewishly, in ways as varied as the Jewish people itself. The #ShowUpForShabbat campaign has been as successful as my synagogue’s bookshelves were bare that Shabbat morning.

***

The first post-shooting Shabbat brought more faces into synagogue, more words, more singing that swelled with more emotion.

What will the coming Shabbats be like?

The first post-shooting Shabbat Eve brought Hebrew letters to the front page of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

What will its pages say half a year from now?

One cannot expect that extraordinary reactions to tragedy can be, or should be, sustained. Humans are not built to be perpetually overextended.

Yet we can all lift our normal up to a new higher madrega (the traditional Hebrew word for a spiritual level). Doing so will take work, from all of us. But when after tragedy we wish we could do more, when we know painfully well how much we cannot do, we must know, too, how much we can.

After the Tree of Life shooting, we can all recommit to being each other’s Jethro, and to the Sinai-like touchstone that every culture has.

If we do so in the victims’ memories, we will keep their presences living. We will have taken an act of evil and used it as an impetus for good.

Noah Lawrence is a legal scholar and a student at New York City’s Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT) Rabbinical School; its mission is to train Orthodox rabbis who are “open, non-judgmental, knowledgeable, empathetic,” and committed to “the larger Jewish community and the world.” Previously, he worked in law and politics, including for Senator Richard Blumenthal, at the Israeli Supreme Court, and at the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague.