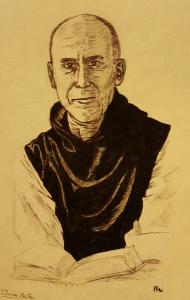

In 1948, the book world’s surprise hit was The Seven Storey Mountain, the autobiography of a Trappist monk named Thomas Merton. That year also marked the centennial of his monastery, Our Lady of Gethsemani Abbey. Over the next few years, Merton’s writings would attract unprecedented numbers of applicants to the monastery. As the year closed, Merton praised “the great sea of graces that was flowing down on Gethsemani.”

In 1948, the book world’s surprise hit was The Seven Storey Mountain, the autobiography of a Trappist monk named Thomas Merton. That year also marked the centennial of his monastery, Our Lady of Gethsemani Abbey. Over the next few years, Merton’s writings would attract unprecedented numbers of applicants to the monastery. As the year closed, Merton praised “the great sea of graces that was flowing down on Gethsemani.”

But during the abbey’s early years, its survival seemed doubtful. Lack of funds and vocations, natural disasters and scandals threatened to end America’s first Trappist experiment. (The first three abbots all resigned.) Merton himself notes, “The devil . . . has spent a hundred years trying to interfere with Gethsemani—and in the early days the battle was not altogether to his disadvantage.”

The Trappists are a branch of the Cistercian monks, a centuries old order. Over time, some Cistercians felt the order’s rule was being inadequately observed. Beginning in 1664, Normandy’s La Trappe Abbey hosted a reform movement. (The Trappists’ official title is “Cistercians of the Strict Observance.”) The monastic day, beginning at 2 a.m. and finishing at 7 p.m., consisted of prayer, reading, and labor. Silence was part of the daily regime, and they developed their own sign language.

As the French Revolution targeted the Church, many Trappists left the country. Some tried to make a fresh start in America, but for several reasons (mostly financial) they didn’t get far. In the 1840s, however, Trappists at France’s Melleray Abbey decided to try again. They purchased a piece of property in Kentucky for five thousand dollars from a group of nuns.

In November 1848, Father Eutropius Proust started off with forty-four monks. He envisioned them working in “the forests of North America, among the tigers and panthers and wolves of Kentucky.” When they arrived, there were no tigers, but there were plenty of other challenges. To attract local support, he built a school, a rare commodity on the frontier. Gethsemani College’s opening in 1851 as a boarding school had long-term consequences, not all of them positive.

In the first thirty years only eight men entered, and they all left. One was a Civil War veteran named Joseph Dutton who worked with Hawaiian lepers for decades. The first to stay was a Texas cowboy named John Hanning. Others came less willingly, troubled priests sent by their bishops to live a “life of penance and prayer.” Over the years, Gethsemani had to work hard to overcome its reputation as a clerical penitentiary.

In 1859, Father Eutropius returned to France for health reasons. His successor, Dom Benedict Berger, led Gethsemani for thirty years. (“Dom” is the official title for the abbey head.) A capable administrator, he held it together during the Civil War. The monks supported themselves through their own labor. (One local proclaimed their cider “superior to the best wine I ever drank.”) For a few years, a group of Franciscan nuns ran a boarding school, but financial difficulties led to an early closing.

When Dom Benedict resigned in 1889, he was in a wheelchair. He had been a stickler for the monastic rule, but his successor took a milder approach. Dom Edward Chaix-Bourbon’s short tenure, Merton writes, “almost ruined” the abbey. It started when he hired an Englishman named Darnley Beaufort as the college headmaster. Claiming all sorts of qualifications, including noble ancestry, Beaufort charmed the guileless abbot, but the monks distrusted him. It turned out they had good reason, for Beaufort was sexually abusing the boys at the school.

Paralyzed by shock and indecision, Dom Edward took no action. The monks lost confidence in him, forcing his return to France. Beaufort was arrested for fraud and embezzlement (but not sexual misconduct). The news made the front pages, and Beaufort ended up in jail. But the whole affair cost the monastery dearly. Merton comments that it was doubtful whether Gethsemani “would be able to endure for fifty years more.”

In 1898, there arrived the man who would revitalize Gethsemani. He was Dom Edmond Obrecht (1852-1935), the last French-born abbot, a larger than life figure. He previously worked in New York as the order’s fundraiser. A sophisticated diplomat whose collection of medieval manuscripts was one of the world’s largest, he was also a born leader who knew how to get things done.

In 1920 he made it a policy not to take any more “penitent” priests, and he started retreats for laymen. In 1912, the college burned down, but the monks weren’t greatly distressed. Most, Merton writes, “felt that God had done them a favor.” When alumni tried to raise money to rebuild the schools, Dom Edmond promptly returned their donations. After his passing, Frederic Dunne (1874-1948) became the first American to head a Trappist monastery.

Born in Georgia, Dunne worked in the publishing industry before entering Gethsemani. Historian Dianne Aprile writes: “He believed in the power of the written word, and sensed the time was right to use it to the monastery’s advantage.” When Thomas Merton entered in 1941, he assumed his writing days were finished, but Dom Frederic encouraged him to continue. During his years there, Merton published hundred of articles and nearly fifty books (all royalties go to Gethsemani).

One hundred and seventy years after its founding, Gethsemani Abbey holds pride of place as Catholic America’s flagship monastery. This makes it easy to overlook the fact that for many of those years, its existence was at best precarious. Its recovery from scandal, and its subsequent revitalization, should offer encouragement to those who ask whether the Church can recover from its present challenges. The Gethsemani story shows that the answer is a resounding “Yes.”

NOTE: The above article originally appeared in Patheos in February 2011, and is reprinted on the occasion today of the fiftieth anniversary of Thomas Merton’s death. The above drawing of Merton is by Pat McNamara.