A Critique of Centering Prayer: Text and Commentary

(I shared online a reflection by the lay Catholic spiritual director Carl McColman regarding Centering Prayer and some of its critics. In a response Fr Tiso noted he’d also written a reflection on Centering Prayer in response to an extensive critique. I read it. And then asked if I could share it at this blog. He graciously agreed. There were some problems with the document as I received it. I’ve tried to capture the quotes from the original article in italics. Any mistakes there, are mine. JIF)

As a priest involved in spiritual direction, I receive many emails and inquiries from people who are genuinely pursuing the spiritual life in the Catholic Christian tradition. Many of them are deeply troubled by the scandals that have emerged from every level of institutional Church life. Others are distressed by the ideological polarization that has come to characterize ministry on the local level throughout the world, particularly in English speaking countries. In the following essay, I am responding to an inquirer who has read a very disturbing article by a follower of the Charismatic Renewal in the southern United States. The author of this article sets about to denigrate the Centering Prayer movement by identifying it with non-Christian forms of spirituality, which are then critiqued according to criteria that do not reflect a due respect for other religious traditions. Moreover, the benchmarks for what is Catholic and Christian in this critique derive more from Evangelical and Pentecostal theologies than from the authentic tradition of contemplative prayer in the Catholic tradition. This is not to say that everything about Centering Prayer is above criticism. However, valid criticism needs to arise from within a tradition whose theology, vocabulary, and methodology are at least coherent and rational. Otherwise, what kind of a dialogue is possible? The phenomenon of polarization within the Church is a clear indication of the loss of a rational, traditional basis for dialogue. Therefore, my responses are meant in the first place to offer charitable correction to the author’s errors in theology, fact, and method. In the second place, my hope is to offer encouragement to those persons who are genuinely drawn by grace to the apophatic contemplative practices supported by the Centering Prayer movement and other groups within the Church. Third, I hope to dissuade Catholic Christians from employing undeveloped theological perspectives coming from some parts of American Protestantism, chiefly because they can also be directed at Catholic practices that we all respect and share as Catholics. And finally, I would like to caution Catholics about some tendencies within the Charismatic Renewal that are potentially sources of divisiveness, polarization, and spiritual abuse. At the same time, in charity, I would hope to avoid the impression that I am trying to crush an uninformed person who is expressing opinions that she is not really able to support with facts. The real issue here is not only that of the ignorance of the author, and not even of the imprudence of the editors in publishing such an article in a pastoral periodical that has the potential to impact church leadership. Even in Europe, we have problems with the anti-Semitism of Radio Maria, and the penetration of conservative Catholic circles of the same fundamentalist pamphlets that our author seems to know quite well. Perhaps the most troubling feature of this essay is that it points the finger squarely at Catholic contemplatives in religious orders who are not adequately teaching the real Catholic contemplative tradition to anyone. The Trappists did their best with Centering Prayer, and it has been an effective means of reaching a wider community of persons seeking deeper wellsprings of prayer. In reality, the level of scholarship even among the Trappists is remarkably low. We hear almost nothing from the Carmelites. The Camaldolese have offered a good deal in the US, India and Europe. My students at the Gregorian seemed to have had almost no training in methods of prayer of any kind, not even the basics of recollection. A young Trappist shared the documents of the Cistercian Exordium with me – I was almost in tears reading these splendid texts. I wanted to run off to join the Trappists! When I participated in the liturgy at their monastery, however, it was prayerful enough, but there were too many shortcuts, too much special pleading in the homilies, to much a mood of “let’s get it over with”. And in fact that monastery is dying out. This was not my first experience of the decline of contemplative prayer in the institutes that were founded to sustain that particular vocation in the Church. Perhaps the time has come to dream up something new.

First, the inquiry:

Francis,

I am sorry that I find myself giving you so many questions.

What do you think of this one? I am reading Fr. Thomas Keating’s Open Mind Open Heart at the present time. It was recommended to my by Sister J., a very close friend.

She made Keating’s ten day retreat this summer and got a lot out of it. In fact she is going to go again next year. Keating makes a lot of sense to me, but maybe I am not as knowledgable about Christian spirituality as I should be.

Dick

Preamble to a response: It is very hard even to read an article like this and keep the virtue of patience in view. The author is building on very poor foundations and strong personal dislikes to vilify people who may be imperfect, but are certainly better informed and more experienced than she is. I will try to keep a cool head because prayer, especially contemplative prayer, should call us to charity and not to anger or contention. I do not now practice Centering Prayer; I prefer to follow the guidelines I find in the works of St. John of the Cross and in the anonymous Cloud of Unknowing in my personal prayer. I studied CP with Fr. Basil Pennington as long ago as 1976 and had many spiritual conversations with him and with Fr. Thomas Keating from 1976 to the mid-1990s. I have also attended programs of Fr. Lawrence Freeman of the International Community for Christian Meditation and have made many retreats in monasteries in the US and in Europe over the years. From 1986 to 1998, I lived in the hermitage of Saints Cosmas and Damian at Isernia, Italy, where I practiced a strict daily rhythm of meditation and contemplative prayer. In that period I had spiritual direction from several experienced monks such as Fr. Mayeul de Dreuille OSB and Fr. Abbot Bruno of the monastery of Praglia, Italy; I was also trained in the ministry of exorcism by Fr. Cipriano de Meo OFM Cap, a disciple of St. Pio of Pietrelcina. I gave a lot of attention to the art of spiritual direction and, particularly, to spiritual discernment. I worked with deeply troubled people over the years, including serious cases of possession, drug addiction, and mental illness. Many of my views were formed in the crucible of personal spiritual practice and daily pastoral care of persons coming to the hermitage for help. This ministry continued in the six years of my service in California. I realize that an entire treatise would be needed to address the concerns of this article. In particular, readers might need better definitions of the terms meditation, contemplation, and contemplative prayer. The four-fold approach that we find in Guigo the Carthusian’s writings is still very valid: we “read” a sacred text in Lectio; we “think about it” in Meditatio; we pray about it in Oratio; and we leave God free to respond to us in His own way in Contemplatio. However, contemplative “prayer” can also mean something like the simple prayer coming from the heart in the form of an aspiration (with a single word or no word at all) or self-offering as in the Cloud of Unknowing: this kind of simple prayer can be very brief and repeated throughout the day; it is not the same thing as “Contemplatio” which is a pure gift response from God to our self-offering. Rather, it is the gift of self in great simplicity by means of an act of intellect and will that is very brief and intense. You learn to do this after much practice in the spiritual life; it is not something “forced” but at the same time it can be distinguished from the utterly free divine response that is true contemplation. What the Cloud teaches is a “contemplative method” by which a person with a special calling to a life of intense spiritual practice develops the “art” of receptivity. This is a “method” oriented towards the free gift of God’s grace.

Unfortunately, the term “contemplate” in ordinary English is all about “thinking about something” and has nothing to do with what we are discussing here. It is not strictly speaking correct to apply the word “contemplation” to “discursive meditation” which is “thinking about a sacred topic or text in a state of deep recollection and prayerfulness.”[1]

I should have gone into greater depth on the difference between a monastic or “contemplative” vocation and the lay vocation. There is a real difference between the two, and it is not based on the “clericalization” of the monastic life; contemplative nuns and monks have a contemplative vocation that has nothing to do with the “lay” state of life and nothing to do with the call to the clerical state either. Some monks have a vocation to the clerical state, which is separate from the monastic calling. Some monastics do not have a contemplative vocation, strangely enough, but are called to the monastic life to develop spiritually in other ways, such as penitence, or in the spirituality of the sacred liturgy.

One of the most troubling features of the article in Homiletic and Pastoral Review is that it has the character of a smear campaign designed to associate the monks who created CP as a lay contemplative movement with various non-Christian ideas and beliefs and, in that way, to discredit CP. Some of the accusations flung at the monks involved with CP amount to calumny, a grievous sin against the eighth commandment. CP is based on ancient and very authentic traditions of Christian prayer and cannot be invalidated by anything that may or may not be associated with Frs. Basil and Thomas. The fact that neither the author nor the editors of HPR seem to know anything about the history and the practice of authentic Christian contemplative prayer, and have promoted a campaign against a viable attempt to teach that tradition, should be deeply disturbing to all faithful Catholics. After all, for many professional Catholics, the writings of someone like Thomas Merton were the mainstay of their adherence to the faith in spite of many challenges over the past 60 years. Merton’s personal practice of contemplative prayer, attested in his journals and in well-known published writings, remains the foundation of what is called Centering Prayer.

It is true that at times some CP teachers have ventured into areas in which they were not well-versed. I have the impression that their involvement in inter religious dialogue, valid as it was, did not adequately prepare them for the critical thinking that is needed in order to respond to the so called “new age” phenomenon. Frs. Thomas and Basil took up topics such as “vibrations”, tarot symbolism, cakras, yoga, and so forth because many educated Christians have encountered these concepts in their reading or other experience. A superficial acquaintance with these terms can be attributed to contact with the “spiritual supermarket” of eclectic ideas in popular books and workshops. These Christians rightly asked for explanations in the light of Christian teachings, especially in the light of Catholic monastic experience and wisdom. Frs. Thomas and Basil attempted to give meaningful answers to these inquiries. For this they are being vilified by people who have formed a negative opinion of these topics, basing themselves on publications that are no less eclectic and ill-informed than those they find distasteful. Even if the publications of Frs. Thomas and Basil contain flaws with regard to non-Christian practices, that does not invalidate their deep experience of the monastic life, of contemplation, and of spiritual guidance. Moreover, there is no reason to think that Mrs. Feaster’s approach would have been effective in responding to the inquiries of educated Christians. Quite the contrary, her approach is most likely to offend people. Not only has her offensiveness created hostile pastoral territory in our own parishes, it has also spilled over into the field of interreligious dialogue to damage a key feature of the Church’s mission in the modern world.

Author of the article:

Margaret A. Feaster

Description:

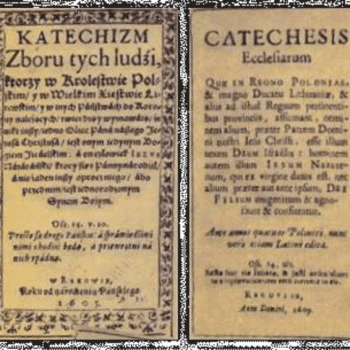

This article examines Centering Prayer as expounded in the works of Fr. Thomas Keating and Fr. Basil Pennington, and compares it with prayer forms common to New Age, Hinduism and Zen Buddhism.

Homiletic & Pastoral Review Pages: 26 – 31 & 44 – 46 Publisher & Date: Ignatius Press, San Francisco, CA, October 2004

Text of the article, followed by a commentary:

“A Closer Look at Centering Prayer”

The Centering Prayer Movement has become very popular in Catholic circles today. People sign up for it in retreat centers, in workshops, and sometimes in their own parish. These people believe it to be authentic Christian contemplative prayer practiced by the saints. Is it really Christian contemplation?

Observation: It would be fair to say that, even after 45 years, only a very small percentage of people participate in Centering Prayer groups. It is true that some Catholic-based retreat centers have programs that are experimental including some that are not exclusively Catholic. The author’s theology deviates from traditional Catholicism in some important ways. The approach is intentionally out of focus right from the start, even though the question as to whether Centering Prayer is “really Christian contemplation” is certainly worth asking. Unfortunately, the author seems to have been more influenced by pamphlet sized fundamentalist propaganda than by careful research in the history of traditional Catholic spirituality. Ironically, by succumbing to this influence, she ends up subverting the spirituality of the early Church, kept alive in Orthodox, Eastern Christian, and Catholic monasteries for centuries. Those of us who have struggled with the subaltern status of Catholic Christianity in the English speaking world are in a position to sympathize with the mistake this author is making, but not to agree with her conclusions. The author goes on:

In my research on the New Age which I did for the past ten years, I found that it is not Christian contemplation and that this type of prayer is not recommended by Pope John Paul II, Cardinal Ratzinger, The Catechism of the Catholic Church, or St. Teresa of Avila. There have also been warnings from Johnnette Benkovic on EWTN (Mother Angelica’s Network). Johnnette has a program called “Living His Life Abundantly”, and has had a series on the New Age. She has also written a book called, The New Age Counterfeit, and devotes one chapter to the problems of Centering Prayer (CP). She identifies it as being the same as Transcendental Meditation (TM) which is tied to Hinduism.

Response: The attacks on EWTN against Centering Prayer are well known and go back several decades. EWTN has been a primary promoter, unfortunately, of the dramatic increase in polarization on the local level that we encounter in many Catholic parishes in the United States. At the present time, EWTN offers Catholics, especially the home-bound, a well-grounded traditional liturgical Catholicism. Unfortunately, the EWTN voice slides perceptibly into polemics against the teachings of the present Holy Father, Pope Francis. EWTN is also allied with the most conservative political voices in American Catholicism, to the chagrin of many Catholics in the US and elsewhere. The author, in her Homiletic and Pastoral Review essay from 15 years ago, is more or less repeating the old criticisms, which have as little merit now as they did then when Mother Angelica tried to destroy the reputation of Fr. Thomas Keating. Also, the approaches identified here with St. John Paul II and Cardinal Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI), though significant and weighty, are not above criticism in the light of careful study of the broad Christian contemplative tradition as well as a balanced study of non-Christian sources. The two Holy Fathers were certainly not out to destroy the apophatic contemplative traditions of Catholicism, and it is an injustice to ally their views on spirituality with such a project.

The author continues: What is Centering Prayer?

Centering prayer, as taught by Fr. Basil Pennington and Fr. Thomas Keating, is a method of prayer that is supposed to lead a person into contemplation. It is supposed to be done for twenty minutes in the morning and twenty minutes in the evening. The person chooses a sacred word. He tries to ignore all thoughts and feelings, letting them go by as boats going down a stream. When the thoughts keep coming back, the person returns to the sacred word. The goal is to keep practicing until ALL THOUGHTS AND FEELINGS DISAPPEAR. Fr. Keating says in Open Mind, Open Heart, “All thoughts pass if you wait long enough.”1 A person then reaches a state of pure consciousness or a mental void. The thinking process is suspended. This technique is supposed to put them into direct contact with God. The idea is to go to the center of your being to find the True Self. This process is supposed to dismantle the False Self, which is supposedly the result of the emotional baggage we carry.

Response: The capitalized words above indicate that the author is worried about states of consciousness in which there are no verbal or imaged thoughts in the mind and in which there are no “feelings”. However, she never defines her terms clearly. The essay, to the discredit of the editors who published it, is an undisciplined piece of writing with obvious polemical intent. In fact, classical Christian contemplation clearly distinguishes between contemplation, which is a grace, a gift of God, from prayer involving thoughts, feelings, emotions, and imagery. The terms “pure consciousness” and mental void are not equivalent. Pure consciousness simply means “awareness” as distinct from particular ideas, images, sentiments, opinions, and so forth, that may arise in the mind. Mental void is the term used by fundamentalist writers who do not understand the Buddhist teaching on “emptiness” (shunyata) claiming that this term has something to do with emptying the mind of thoughts in a forceful way to get into a state of trance. This is completely untrue. Another misconception arises from a misunderstanding of the yoga teaching on “citta – vritti – nirodha” which means: “the thinking mind’s vibratory phenomena come to a halt”. This does not mean, as some polemical writers would have us believe, to enter into trance states. It simply means that awareness is present and the various mental phenomena of thoughts, memories, opinions, sensory data, images, etc. cease as a result of prolonged meditation practice. The cessation is not forced, but it is certainly “occasioned” by mental discipline or meditation. Eastern masters recognize the characteristics of trance states and are very concerned that their students not fall into trance states or “torpor” because these states can degenerate into undesirable contact with the spirit world. Like Christian masters, they do not want their students to be channeling spirits or becoming mediums. Eastern masters in both the Hindu yoga and Buddhist meditative traditions are well aware of the need for an experienced spiritual guide and have a long, carefully documented history of spiritual teachings that help avoid pitfalls on the spiritual path. Our author never mentions any of this, and seems not to have any knowledge of the spiritual director’s role in contemplative practice at all. It is also pertinent to observe that all contemplative traditions give evidence of producing well-balanced, healthy individuals who did great things for their time in history. One is not always in a state of contemplative absorption! The descriptions of certain experiences of deeper prayer refer to transient states that are not in themselves the highest condition of a human being. The highest state is to be spiritually aware and morally generous at all times, under all circumstances. This is a teaching that masters east and west have emphasized for centuries: it is all about discernment and discretion. The description of the method of Centering Prayer given by the author is a clear indication that the author has acquired some prejudices from outside the Christian contemplative tradition about which she knows very little. Anyone who has read St. John of the Cross knows how rigorous this Doctor of the Church is with regard to thoughts, attachments, emotions, and a host of other psychological factors that reflect spiritual immaturity. Centering Prayer as a movement is offered to lay people, not to consecrated persons in contemplative orders. A restricted number of faithful Christians (and others) have already had baffling subjective experiences of a mystical type. They often ask for guidance in trying to understand these experiences. They would like to move toward a deeper form of prayer in harmony with the contemplative methods that have been known to our Catholic tradition for more than 1500 years. Centering Prayer offers methods that are tailored for the laity. As we know from experience among both clergy and laity, a gentler approach is sometimes necessary in our destabilized times. The kind of guidance that Fr. Thomas Keating offered in his publications reflects his experience of listening to persons who chose to remain within the Catholic tradition, having had some contact with [mainly] Buddhist teachings on meditation. It was therefore entirely to be expected that the method of presentation should reflect the contents of the teachings and experiences with which this particular group of people find congenial. What is also important in this conversation is to recognize that many of the Buddhist teachings on the deeper practice of meditation correspond to the traditional Catholic teachings on contemplative prayer. With due sympathy for the author, it would seem that the community of discourse to which she belongs is not, in fact, the Catholic contemplative tradition, but something outside and even hostile to it. She continues:

Fr. Thomas Keating is a monk, priest, and abbot of St. Benedict’s Monastery in Snowmass, Col. and is the founder of the Centering Prayer movement. He has written four books. Fr. Basil Pennington is a Trappist monk at St. Joseph’s Abbey in Spencer, Mass. He has written over thirty books, some of which are on Centering Prayer. Some of the concepts in their books are similar to New Age beliefs and practices.

Response: First of all, it is a good thing to check our facts: Fr. Thomas Keating was Abbot of St. Joseph’s Abbey, Spencer, MA. He was never the abbot at Snowmass. It might have been even more helpful had she examined her own conscience to ask how someone who had guided hundreds of people (even thousands) might merit the unqualified insinuations she levels at him. I can recall many one-on-one conversations with Fr. Thomas Keating, some of which gave me enduring spiritual insights, and at least one of which brought me to tears of spiritual joy and consolation. As for Fr. Basil, I did not always agree with him when he was alive, but I do know that he was a humble man, sincere in his teaching, open to dialogue with others. The author who writes insidious essays about other people is usually not a reliable spiritual guide for anyone. Such people exaggerate the faults of others so that it is not necessary to offer a balance sheet of the positive and negative features of their published writings. When Fr. Basil went to Mount Athos to consult with the Orthodox monks, they told him that Centering Prayer would be considered a valid and sublime form of prayer in their tradition. The fact that the communities most committed to the preservation of the apophatic contemplative tradition would have found Centering Prayer “sublime” is particularly convincing, especially when we know how fierce these same Orthodox monks can be in their own polemics against both “New Age” and Pentecostal spiritual systems. Unfortunately, our author belongs to an anti-contemplative theological community of discourse. This makes dialogue very difficult. In the system, typical of fundamentalist fervor, religious emotions and “piety” were given considerable importance in the life of a serious Christian. Conversion is understood to be an emotional experience, almost a form of psychological break down. Religious emotions, or as their opponents termed it, “enthusiasm”, was their substitute for interior spiritual transformation by means of sanctifying grace. Contemporary fundamentalists in the US, like their early Reformation forebears, do not believe that human beings are sanctified by the sacraments. There is no baptismal regeneration, nor can there be spiritual transformation in this life. The author would have done a much better job if she had actually met with and spoken with the people she wishes to criticize. It would also have been useful for her to have studied the traditional works of Catholic theology that alert us to the deviations that characterize fundamentalist Christianity. The author now presents a perspective on other religions:

What are New Age Beliefs?

New Agers borrow many of their beliefs from Hinduism. They believe that we are all connected to an impersonal energy force, which is god, and we are part of this god. This god-energy flows into each one of us; so we too are god. (This is the heresy of pantheism, condemned by the Church at the First Vatican Council).

Response: Perhaps no movement is as susceptible to polemical garbling as the so-called “New Age”. It is a no-man’s land of syncretism and imprecise vocabulary. It is also extremely offensive to the multi-millennial traditions of Hinduism to identify them as the source for the bewildering rhetoric that typifies the “new age” environment. Even less does any of this have to do with Centering Prayer, which is essentially the apophatic tradition of contemplative prayer attested by the great twelfth century Victorines (Hugh and Richard), by St. Bonaventure and St. Thomas Aquinas, by Meister Eckhard, by the anonymous Cloud of Unknowing and other fourteenth century English mystics. The tradition of apophatic, or imageless, prayer was, and remains, one of the most profound and creative approaches known to the Catholic tradition. Fr. Basil told me that he was introduced to this spirituality by one of the older monks in the community at Spencer, as if it were a special gift of the Holy Spirit to the Cistercian Order. Nothing could be farther from the contemporary syncretism associated with the “New Age” or the pseudo-yoga spiritual supermarket, including “Transcendental Meditation”.

Some Christians, fundamentalist, Pentecostal, and others, may at times call “grace” a sort of bodily feeling or emotion; others might employ the term energy (after all, the New Testament speaks of exousion and dunamis in the miracles of Jesus). It is hard to tell whether these Christians are talking about an experience, a sensation, a metaphor, or something very subtle. However, the Pentecostal and Charismatic Renewal movements make ample use of this kind of terminology to describe a very emotional, embodied form of spiritual experience. Is the pot calling the kettle black? Our author is involved with the Charismatic Renewal.

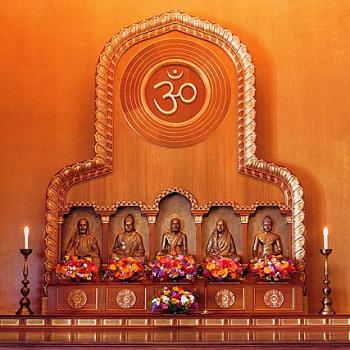

There is an idea in the New Age[2] movement that the universe is the body of “god” (the Gaia hypothesis) that has some philosophical and scientific ramifications, not all of which are without problems. We are thus all part of this time-space-matter-energy universe, which is self-contained and perhaps even self-produced; there is no “external God who is the Creator of all things from nothing”. This viewpoint is not the same as Hinduism, which believes in a purely spiritual nature to God and sees all phenomena to be woven out of the spiritual nature of God in the process called “maya” – which is sometimes translated “illusion” but more accurately as “a magical display”. Through spiritual practice, the human being discovers the “trick” that the material universe is playing on us, recognizes his or her truly divine nature (one in substance with God in most Hindu systems, but not all), and attains spiritual liberation (moksha). For the New Age, everything is just what is here and there is no transcendence; for Hinduism of all kinds (dualist or non-dualist) there is a true intuition of transcendence. Some Hindu systems do not believe that the human soul is identical in substance with God; one has to be careful not to over-generalize.

The author continues:

They think because we are god, we can create our own reality, experience our own god-power. This awareness of our godselves is called god-consciousness, super-consciousness, Christ-consciousness, pure-consciousness, unity consciousness, or self-realization. To reach this awareness, New Agers use mantras or yoga to go into altered levels of consciousness to discover their own divinity. They look inside to find their True Self or Higher Self – to find wisdom and knowledge since the True Self or Higher Self is god.

Response: The English language in the hands of an amateur is going to have some difficulties wrapping itself around the plethora of spiritual teachings that have been translated into English at various times in our history. What we need to do is to gain familiarity with the real teachings of the real saints and mystics of all traditions so that we can filter out the sloppy use of terminology in popular media. Let us look at something close to the Catholic tradition. When Thomas Merton was talking about the True Self he was not talking about the Hindu “atman” (self) which the Upanishads say is of one substance with God (atman = Brahman). He was working with the young Trappist monks who often came to the monastery with mistaken ideas about themselves, their vocations, and the nature of the monastic life; he had to help them find their true vocation, and in so doing find the “true self’ which is the identity that God has always wanted for us: our sanctification. The False Self for Merton[3] was the collection of mental baggage, pious and otherwise, that we allow to set limits and conditions on our behavior. Asceticism and prayer, under spiritual guidance, are the traditional ways to dismantle the False Self. Keating explains this in his books as the false search for emotional satisfaction. This seems about as far as could be imagined from “new age” thinking, which often mistakes well-being for self-gratification.

They address god as the Source, the Divine Energy, the Divine Love Energy, or the Great Universal Intelligence. The goal of New Agers is to usher in a new age of peace, harmony and unity.

Response: I certainly hope that Christians are also interested in peace, harmony, and unity. They hope that all mankind will come to “god consciousness,” which is the awareness that they are god.

Response: If this means the “non-dualist” (advaita) notion that the human soul is of the same substance as God, this would certainly not be a Christian teaching and could not be held by an orthodox Christian. If non-dualism means that there is no transcendence and everything is space-time-matter-energy, self-arisen or “self-organized”, it would not be Christian belief. Spiritual practices designed to reinforce such belief would not be Christian. In fact, new age non-dualists usually have only the vaguest notion of the relationship between their ideas and the real philosophical positions characteristic of orthodox Hinduism. The real problem would be with the science-oriented public that is doing everything in its power to deny the doctrine of Creation, substituting the theory of the self-organization of matter and energy. However, Centering Prayer does not endorse any of these philosophical positions, nor do the published works of the authors cited fall under this criticism.

The complete definition on the New Age by Fr. Mitch Pacwa is as follows: “The New Age Movement is highly eclectic, borrowing ideas and practices from many sources. Meditation techniques from Hinduism, Zen, Sufism, and Native American religions are mixed with humanistic psychology, occultism, and modern physics.”2 There is a scripture in Col. 2:4-8, that warns us against this pitfall. It states, “I tell you this so that no one may delude you with specious arguments . . . See to it that no one deceives you through any empty philosophy that follows mere human traditions, a philosophy based on cosmic powers rather than on Christ.”

Response: It cannot be sustained that the passage in Colossians, which is extremely vague, has anything to do with the topic we are discussing. Perhaps the author of the New Testament passage (a disciple of St. Paul?) was referring to some branch of Hellenistic philosophy, but the allusion is far from precise. Fr. Pacwa’s observation that new age is eclectic and imprecise is most certainly correct, and for that reason the so-called “new age” has nothing to do with the Catholic contemplative tradition, including Centering Prayer. Unfortunately, by suggesting that “new age” borrows from the historic, ancient, and significant traditions of Zen, Hinduism, Sufism, and Native American spirituality has a number of extremely negative consequences. In the first place, it opens up the Christian traditions to the accusation of racism and colonialism, which at the moment are inflaming anti-Christian sentiment around the world. Second of all, by practically accusing these traditions of being the source of an irresponsible form of behavior is to create prejudices and obstacles at the very moment in which we are in need of rational inter religious dialogue. As for occultism, who knows what Pacwa means here? As for humanistic psychology, if he means the work of Roberto Assagioli (psychosynthesis), I would suggest reading the well-balanced essay “Spiritual Development and Nervous Diseases”, from 1933, which offers suggestions that most Catholic spiritual directors would find congenial. Of course, he may mean something else, since Pacwa’s terminology is vague. Finally, the damnation of modern physics seems to have reached the limit of what is rational in this brand of contemporary Christianity. They know nothing, they are in dialogue with no one, they have no positive contribution to make, and so they establish their position by innuendo and denigration. We are dealing here with the kind of fundamentalism that sooner or later breaks out in violence. The text continues:

How do New Age Beliefs Compare to Centering Prayer?

In CP, people are taught to use a prayer word or sacred word to empty the mind.

Response: This is completely false. The prayer word is used to focus the attention on the presence of God (something absolutely crucial to Centering Prayer) in faith and love. When the mind wanders, it must be brought back to clarity, as anyone knows who practices prayer regularly. Distractions at prayer are a common theme in Catholic spiritual writers down through the ages. The method is perfectly traditional. You cannot really “empty” the mind by any artificial technique, in part because then the technique comes into the mind and so the mind is not empty; it is circular and self-contradictory. A stillness of the mind can occur from time to time in prayer, and that stillness makes it easier to be aware of God’s presence, working in our souls by the power of grace. Centering Prayer affirms this traditional teaching; I know this from personal conversations with both Frs. Keating and Fr. Pennington. The use of the prayer word is clearly expounded in the very traditional Cloud of Unknowing. The fact that the author does not know this is an indication of a lack of background in even the most basic features of the authentic Christian contemplative tradition.

Continuing: (Fr. Keating says it is not a mantra; but if it is used to rid the mind of all thoughts and feelings, then it does the same thing as a mantra).

Response: Mantras are used for a variety of purposes; the yogis are not philosophically naïve; they know that if you fill the mind with a mantra, the mind is not empty. In CP, the purpose of the prayer word is simply to keep prayerful awareness focused. In the rosary, or in one of the classic litanies, the words of prayer have exactly the same purpose: focusing attention on the Presence of God as we pray. In prayer, we want to allow God’s grace to free us from the attachments, emotions, feelings, and thoughts that distract us from God. The way to love God is God’s own gift of Himself to us in this deep form of openness in contemplative prayer (cf. St. Augustine, Discourses, 36). In Fr. Joseph Marechal’s classic study of the psychology of mystical experience, presence was one of the most consistent experiences known to Catholic religious in the first decades of the twentieth century.

And again: The goal is to reach a mental void or pure consciousness in order to find God at the center.

The author here is following a common trope in the fundamentalist anti-meditation pamphlets: that meditation creates a “void” in the mind that, they claim, can be filled by a demonic presence. In reality, masters in the other religious traditions are also aware of this risk, and are well trained in methods of protecting the mind during meditation from interference. In total contrast with the view of the author, one does CP by silently and attentively allowing God’s presence to be the primary focus of awareness, allowing God to work in us freely. Mental void and pure consciousness are not goals of CP; they are not terminology that one finds in many non-Christian traditions either; one does find “pure consciousness” or “awareness” in some traditions to describe the mind as it abides without thoughts, but even this corresponds to the imagery of the mind as a mirror that is found quite frequently in our own tradition.

Pure consciousness is an altered level of consciousness.

Response: This is not true. It is just the mind as potentially capable of receiving images, without the mind creating imagery on its own. The image of a clean mirror is a well-known metaphor in all traditions, East and West, for this. On a deeper level, however, we can find an altered state of consciousness beautifully described by St. Teresa of Avila in the prayer of quiet. It is a pure gift of grace, an inner silence in which the person is filled with God’s silent presence. St. Teresa considers this an important stage in the development of contemplative union with God.

This is exactly what the Hindus and Buddhists do to reach god-consciousness or pure consciousness.

Response: The author is not well informed here and ought to ask a Hindu or Buddhist master to explain the point. In dialogue, we listen to others and take seriously what they say. We rely on those teachers who give good evidence of having the appropriate formation and experience.

This is also similar to what actress Shirley MacLaine does to go into an altered level of consciousness and discover her Divine Center or Higher Self, which is her divinity.

Response: It is simply incredible that a line like this should have slipped by the editors of a Catholic pastoral publication. It borders on calumny. After all, what does Shirley MacLaine have to do with real Buddhism or Hinduism? Again, a Christian author has to be truthful, just, and charitable.

What are the Similarities Between CP and TM?

The author goes on: Johnnette Benkovic has interviewed people on her show and in her book who have done both CP and TM. They claim it is basically the same. The only difference would be that in TM the mantras are names of Hindu gods, and in CP the sacred word is usually Jesus, God, peace, or love. Fr. Finbarr Flanagan, who was involved in both CP and TM says CP is TM in a Christian dress. He says Fr. Pennington has endorsed TM “. . .without hesitation.”3

Response: Fr. Pennington was naturally very enthusiastic when he would meet like-minded, idealistic people. There is no requirement that we agree with everything he wrote; sometimes, perhaps, he was too open-minded. It is also true that he and other CP teachers felt that the public ought to know about Christian contemplative practice and that the TM people had devised a useful way to “package” their teachings. I think it would be fair to say that the similarities between TM and CP can be reduced to a method of marketing, and not to the substance of the teachings involved. Thus, CP was presented in workshop format; but this is not the way it was lived in the monastic environment. I think the author would have done the Church a better service by helping readers recover the monastic roots of CP, the interplay of silent prayer and chanted psalmody; the periods of lectio divina (which Fr. Keating has encouraged as a necessary preparation for and development of what one discovers in CP); times of silence during the day; personal prayer of the monk, especially those more open to the graces of contemplation, and so forth. Recovering this context might soften her criticism of CP and deepen her own practice of prayer. After all, in our tradition, the spiritual director or teacher do not bestow God’s grace on the contemplative person. Priests do so in the sacraments they celebrate as priests. Only God can give what God wishes to give to every hungry soul.

Let’s look at the similarities:

1) Both CP and TM use a 20-minute meditation.

2) Both CP and TM use a mantra to erase all thoughts and feelings.

Response: Almost all meditative traditions work with sessions of practice and quite frequently 20 minutes is the time suggested. How this “proves” something insidious is beyond my ability to understand. The persistent misrepresentation of “erasing” thoughts and feelings is a misunderstanding. Besides, as one grows to appreciate the gift of silent prayer, one just spontaneously realizes how refreshing it is not to have thoughts and feelings for a while, but this is not something that you can force the mind to do by willing it. The best one can do is to nurture a prayerful state of recollection and work with the prayer word. By the way, in the Cloud of Unknowing, the prayer word is used to carry the intensity of the heart’s longing for God toward the Presence of God; it is not a remedy for distracting thoughts. This is something not clear in the author’s presentation, and at times it is not clear in CP presentations either. I have felt that the CP workshops should go into greater depth with the classical texts such as the Cloud and related texts, Carthusian spiritual writings, St. John of the Cross, the Victorines, the Byzantine Philokalia, and so forth. This is one of the reasons I am writing this book.

3) Both CP and TM teach that in this meditation you pick up vibrations.

Response: The author will later on tell us that she is suspicious of these vibrations, as if they were a form of occultism (which she never defines). Subtle sensations do occur in contemplative prayer; they are transient and not very important, but it is useful to take note of these phenomena and share them with the spiritual director. The Spanish Carmelites speak of divine “touches” (toques).

4) Both CP and TM claim that this meditation will give you more peace and less tension.

Response: Is this a bad thing? Look around us at entire populations addicted to opioids.

5) Both CP and TM teach you how to reach a mental void or altered level of consciousness.

Response: Again, the author egregiously repeats her misunderstanding of the terminology that could be corrected by speaking with practitioners of virtually any contemplative path.

6) Both CP and TM have the common goal of finding your god-center.

Response: CP was never taught using those terms and in my conversations with Fr. Basil and Fr. Thomas neither of them said anything of the kind. In the Liturgy of the Hours, there is a reading from St. Gregory of Nyssa pointing out that the encounter with the deepest self is a way towards encountering the “face of God.” The author needs to study the Christian contemplative masters.

In regard to vibrations, Fr. Keating says, “As you go to a deeper level of reality, you begin to pick up vibrations that were there all the time but not perceived.”4 Fr. Pennington also speaks of “. . . physical vibrations that are helpful”5 (Vibrations are common TM, New Age language.) Using mantras and reaching a mental void are also New Age, not Catholic. In fact, reaching a mental void is described in the Catechism as an erroneous notion of prayer (#2726).

When Does the One Who Prays Cross the Line into Hindu/Buddhist/New Age Prayer?

In the beginning stages of CP, the one who prays is still ignoring thoughts as they float by. If they are still thinking of Jesus or heavenly things, they are still in Christian prayer. They cross the line when they get to the point where they bypass all thoughts and feelings.

Response: I think it would be fair to say that this criticism could be leveled at all forms of Christian monastic prayer in which recollection is the key to the practice. In the document Orationas Formas of 1989, this insistence on having thoughts, emotions, and experiences was criticized as a form of the heresy known as Messalianism. (See section 2) This criticism coming from a document that was in many ways unhelpful to inter religious relations, and even less so to Christian contemplatives, might easily be leveled at the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, of which the author is a member. Certainly the state of apatheia or impassibilitas, discussed also in this document, goes beyond thoughts and emotions; and it is to be understood that apatheia is not the pinnacle of transformative union. The author risks bringing not only CP into disrepute, but also Eastern Christian hesychasm, which would damage our dialogue with the Eastern Churches. It is interesting that Orationis Formas specifically expresses admiration for the hesychastic apophatic prayer practices of the Eastern Christian Churches, which as we have indicated above, are similar to Centering Prayer. Hesychasm emphatically rejects thoughts, emotions, attachments, and images as obstacles to true interior prayer. The Cloud of Unknowing reminds its readers that even pious thoughts, however theologically correct, are not the Presence of the Living God. In order to enter into contemplative union with God, only a naked intent of love for the Living God is needed, and that love is present with God at the center of our being.

In other words, there are no thoughts at all. Fr. Thomas Keating says in his book, Open Mind, Open Heart, “As you go down deeper, you may reach a place where the sacred word disappears altogether and there are no thoughts. This is often experienced as a suspension of consciousness, a space.”6

Response: Both St. John of the Cross and St. Teresa of Avila, as well as other classic mystical doctors of the Church, recognize this reality and describe it from their own, and others’, experience. It most certainly is Christian contemplative prayer. Please see the index to the complete works of St. John of the Cross for many topics related to this experience. The English version unfortunately does not have an index, but the Italian and Spanish editions do. You can find topics such as: annihilation; apprehensions; contemplation; contemplatives; self knowledge; devotion; delight; God; spiritual director; fantasy; gluttony; imagination; intellect; meditation; memory; means; things noticed; active and passive nights of the senses and of the spirit; prayer (oration); perfection; poverty of spirit; presence of God; beginners; proficients; prayer of quiet; recollection; silence; stripping away; pride; darkness; mystical theology; divine touches; union; corporeal and imaginary visions; will; emptiness. All these topics would be of great value to the author in clarifying her understanding of authentic contemplative prayer in the Catholic tradition.

The exact place in which St. John of the Cross gives the signs for recognizing in spiritual persons when they should discontinue discursive meditation and pass on to the state of contemplation is in The Ascent of Mount Carmel, Book II, Chapter 13 (cf. also 14, 15, 16, for further teaching of great value). It is Fr. Thomas Keating who is authentically representing the Catholic contemplative tradition, and not our author.

When a person is able to do this, they have crossed the line into Hindu/Buddhist/New Age prayer. HE IS NO LONGER PRACTICING CHRISTIAN PRAYER.

Response: This is false, and borders on calumny. Here we are approaching the real heresy at the heart of the author’s argument: contemplative prayer as it has been taught and practiced in the Catholic tradition for centuries is not Christian prayer.

Fr. Keating wants his followers to let go of even devout thoughts. He says, “The method consists of letting go of every thought during the time of prayer, even the most devout thoughts.”7 (In Christian prayer, devout thoughts are important and desirable.)

Response: The Cloud of Unknowing makes it very clear that an attachment to pious thoughts can get in the way of God’s grace working in the soul; in fact, sometimes a very rigid personality clings to such thoughts precisely in order to keep God’s transforming grace far away. These souls experience states of fear when they are in silence and recollection. It takes time, guidance, and grace for them to overcome these fears of “the void” but when they do, they see that God was guiding them all along. This is a key feature of growth in the interior life. Here, too, the author of the essay falls outside the purest stream of the Christian contemplative tradition.

He [Fr. Keating] also tells his followers to let all feelings go. To do this, one would have to let go of any sentiments of love toward Jesus, the Heavenly Father, or the Holy Spirit.

Response: This is not true at all. What is let go of is the habit of clinging to these sentiments because of a fear of losing one’s autonomy, of one’s ego. Often souls identify themselves with Jesus, but in fact they are just worshipping themselves; they cling to their own ideas about Jesus, God, holy thoughts, and virtues. When grace challenges them to let go of these limited opinions, they resist. St. John of the Cross describes this very accurately and shows how the Holy Spirit liberates souls from this error. It is spiritual sensuality, and it is one of the imperfections that the Dark Night of the Soul removes.

The Author invokes authority without understanding the purpose of documents of the magisterium:

What Does Pope John Paul II Say About This Type of Prayer?

In Cardinal Ratzinger’s booklet, Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on Some Aspects of Christian Meditation, he quotes the Pope.

Response: This booklet (Orationis Formas, 1989) should not be ascribed to Cardinal Ratzinger. It came from the CDF under the Cardinal’s direction and was approved by the Holy Father, but it has multiple authorship; it also contains some serious problems because the authors seem not to have understood the Western Christian apophatic tradition of contemplation, or at least not to have been sympathetic to this tradition. Later responses to this document from monastic circles asked that the document be revised on the basis of the living tradition of the Benedictines, Camaldolese, Trappists, Carthusians and other ancient monastic orders. It is thought that the basic text was outlined by Fr. Hans Urs von Balthasar, whose views on contemplation reflect the kataphatic, not the apophatic tradition. The final section, on Eastern Christian hesychasm, is a corrective added to bring some balance into the document.

On p. 34, footnote 12, he [presumably Cardinal Ratzinger] writes “Pope John Paul II has pointed out to the whole Church the example and doctrine of St. Teresa of Avila who in her life had to reject the temptation of certain methods which proposed a leaving aside of the humanity of Christ in favor of a vague self-immersion in the abyss of divinity. In a homily given on November 1, 1982, he said that the call of St. Teresa of Jesus advocating a prayer completely centered on Christ “is valid even in our day, against some methods of prayer which are not inspired by the gospel and which in practice tend to set Christ aside in preference for a mental void which makes no sense in Christianity. Any method of prayer is valid insofar as it is inspired by Christ and leads to Christ who is the Way, the Truth, and the Life” [(cf. John 14:6). See Homilia Abulae habita in honorem Sanctae Teresiae: AAS 75 (1983) 256-257].

Response: It is very important that we not think that this discussion, which is a very complex one, requires the Christian at prayer to occupy the mind with forced or artificial mental images of Jesus, God, the saints, or any particular concept or notion. It is important to note, even from the Collect for the Memorial of St. Teresa, that her way of prayer was “new” and certainly does not abrogate earlier prayer methods and traditions known to the ancient and medieval Church. This is clearly discussed in Orationis Formas section 4, Questions of Method. The document in section 5 also recovers with great esteem the Eastern Christian methods outlined in the Philokalia that explicitly advise against using visualizations of any kind. The methods of hesychasm are rigorously apophatic in theology and approach. St. John of the Cross is more nuanced. He taught that the Holy Spirit leads us away from visualizations and discursive meditations by giving us certain observable signs; with the help of a spiritual director, the contemplative is to abandon discursive meditation and visualizations to allow God to work in the soul without these encumbrances. This is a very delicate matter, and seems to be what the reference to “vibrations” is really about. At a certain point, making use of objects of art, in particular the kitsch art that oppresses the imagination of many Christians, needs to be set aside so that God can teach the soul in silence how to love purely and simply. Perhaps CP has not been as candid about the process of discernment involved, but instead gave the apophatic methods to people who were not grounded in the mature religious affectivity that a period of discursive mediation nurtures. This has been my own personal criticism of CP for a number of years. Here we have the problem of “contemplative methods” as distinct from “contemplation” per se. CP has been taught in ways that are open to criticism. For one thing, there is a lack of attention to the purgative and illuminative ways; in part this may be the a reaction to an excessive emphasis on these aspects of the spiritual life in the past. Too much attention was given to the struggle against sin and the acquisition of the virtues, so much so that one never got to a thorough understanding of the unitive state. Many people suffered from years of aridity and scrupulosity, in an exasperating effort to convict themselves of sin. As a result, many good souls thought that they were abandoned by God when in fact they were in the state of contemplation! No one is doubting that all of us need to work on the struggle for virtue and the avoidance of sin. Here, too, the Cloud of Unknowing offers a great deal of wisdom and equilibrium. Another problem with CP has been the lack of a teaching on discursive meditation other than lectio divina; there is no presentation of affective forms of discursive meditation as would be found in classic “mental prayer” methods, such as that of St. Ignatius of Loyola and St Theresa of Avila. Again, in the past mental prayer was too schematic and artificial. Both St. Teresa and St. John of the Cross observed that mental prayer can become an obstacle to spiritual growth when it is used for too long in the course of monastic formation. However, wisely used, it is a vital way to grow in the virtues and to mature one’s religious affectivity. If it is prolonged beyond this level of maturity, it can lead to the aesthetic pathologies that Merton identified in his posthumous book, The Inner Experience and in his brilliant essay, “Absurdity in Sacred Decoration” – an essay that bears re-reading. Another problem with CP is the fact that they do not go into the three signs that St. John of the Cross considers crucial in discerning an inner call to contemplation; thus they give the impression that all you need is a basic interest in the topic to have such a call; this is not quite true in practice. There are many unbalanced people who are attracted to “higher spiritual practices” in all religions; such persons usually need guidance from spiritual teachers who know how to cure this set of pathologies. Also, in some CP groups there is a reluctance to address morally problematic behavior; a certain moral relativism is present largely because many spiritually inclined people have suffered a great deal from Christian moralism, so they go to the other extreme. It is hard to keep a balance; it would be good to keep in mind that we are all in a growth process and that it is normal to have moral failings. What counts is a willingness to grow, to change, to make amends, to be honest, and to hold on to an ideal of virtue and holiness. Another troubling aspect of CP is the apparent lack of vocations coming from the meditation groups to enter the consecrated life, priesthood, or monastic life; few conversions to the Catholic faith, and so on. We would expect this in a fervent group of contemplatives. However, I do not have any statistics to back this up. I do know some CP practitioners who, over many years, show remarkable signs of spiritual maturity.

It is important for the author to realize that the mentality represented by her essay gives rise in parishes to severe prejudices not only against other world religions, but also against the Christian contemplative tradition. Persons who have been rejected when they asked for teachings on Christian contemplative prayer often wander off to Eastern religions in search of guidance. The CDF document Orationas Formas does not cut off contemplative practice from the laity; instead it prudently balances contemplative practice with ordinary lay piety, sacraments, liturgy, Scripture, and the works of mercy. But the author of this essay goes beyond the bounds of prudence and balance.

Being inclined towards the fundamentalist forms of Christianity, she risks throwing out the mystical theology of the Orthodox and Catholic traditions. She would do well to reflect on her point of view, which is overly influenced by non-contemplative forms of Christianity, and leave some room to those who have other, and perhaps more traditional, approaches. Sometimes our answers can be skewed by the source of the questions! This is as true for some aspects of CP as for many aspects of the Charismatic Renewal. This does not mean that we should not learn from others, but we should not stop learning from our own tradition. We should also be actively teaching the traditional forms of Christian prayer in all their rich diversity, which seems to be the core message of Orationis Formas. My own solution would be to seek answers as much as possible in the classics of Christian spirituality, so that my responses to the questions that modern people ask will be both “modern” and yet “controlled” by the heritage of mystical teachings within the Church.

But the attack on tradition continues: What Does St. Teresa of Avila Say About Contemplation?

Throughout their books, Fr. Keating and Fr. Pennington mention St. Teresa of Avila, implying that she is an advocate of their prayer techniques. However, after reading her books, I have found that her teachings on prayer are the opposite of what Keating and Pennington are teaching. First of all, she says that contemplation is a gift from God, and no technique can make it happen. She says it is usually given to people who have a deep prayer life and are practicing many virtues, although God can give it to anyone he chooses. She repeatedly insists that contemplation is divinely produced. She said that entering into the prayer of quiet or that of union whenever she wanted it “was out of the question”8 She also said in her book, Interior Mansion, “For it to be prayer at all, the mind must take a part in it.”9

Response: Everything St. Teresa is saying here is perfectly fine and does not contradict anything that a right understanding of CP would indicate. We also know that the mind is a more complex reality than what perhaps St. Teresa was in a position to articulate in her times. One thing does happen in doing daily meditation of a discursive kind: you make use of the mind when grace does not move you to silence; usually the mind is working with an outline or a text of scripture (lectio divina); this is recognized by CP. There is no reason to seek an aggressive alliance with St. Teresa in order to denigrate the “contemplative methods” of CP.

Cardinal Ratzinger, in his booklet, also quotes St. Teresa as saying “the very care not to think about anything will arouse the mind to think a great deal”, and that the separation of the mystery of Christ from Christian meditation is always a form of “betrayal”10 St. Teresa advised her nuns to meditate or think about the Passion of Christ as a preparation for contemplation.

The Catechism describes contemplation as “a gaze of faith, fixed on Jesus” (#2715). The focus is Jesus and the heart is involved.

Response: The “gaze fixed on Jesus” is not about gaping at a picture or forcing oneself to dream up a mental image of Jesus. So many people have come to me for spiritual direction over the years, heavily burdened with alienation from the kitsch aesthetic that is imposed on us in so many parishes and religious houses. The “gaze fixed on Jesus” is a much subtler awareness of the presence of Jesus’s glorified body living among us. This is why contemplative prayer before the Most Blessed Sacrament is so helpful towards nurturing interior prayer. The Host is the real Presence, without any image or picture, and allows Jesus to speak directly to the soul. Here we begin to understand what “naked faith” is really all about: it means learning how to receive the gift from God, and not to try to force things by using the imagination. It is true that techniques cannot make contemplation happen: it is in fact a grace. But Fr. Ott also reminds us, as does Tanqueray, that we prepare ourselves for contemplation by “meditation” and “lectio”. Contemplative “methods” are about training ourselves in the art of receptivity, which is most certainly at the heart of CP. St. John of the Cross, as I have said above, makes it clear how the Holy Spirit leads the soul to imageless, simple prayer. It is also useful to remember that Jesus is present in the Church, in the community gathered around the contemplative soul, and that in fact the body of the contemplative person is also sanctified and participates in contemplative prayer. Thus the posture of the body is relevant and needs some of the insight provided by physical yoga practices in order to sustain a life-long commitment to the discipline of interior prayer through times of aridity, illness, temptation, and sufferings.

Above all, one needs to study the Eastern Christian teachings on prayer of the heart, the “nous” of “noetic” prayer, that is most certainly a gift of grace and has nothing to do with visualizations or emotions. In recent years, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has had to reprimand certain Catholic authors (e.g. Fr. Groppi) who had published books claiming that their contents were “locutions” from Jesus and Mary, obtained in visionary altered states of consciousness. Here we have clear evidence of the danger of confusing our own mental images with the gift of divine grace. One of the best arguments for prayer without images is that overdoing the kataphatic practices sometimes does lead a person to confuse the contents of one’s own mind with special revelations coming from God in the form of locutions and visions. All the spiritual writers warn against these deviations.

The author continues: What are the Warnings on Mind-Emptying Prayer from Cardinal Ratzinger?

Christians dabbling in Eastern religions in the 70s and 80s had become such a problem that the Vatican had to respond. In 1989, Cardinal Ratzinger of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, put out a document called “Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on Some Aspects of Christian Meditation.” The document states, “With the present diffusion of Eastern methods of meditation in the Christian world and in ecclesial communities, we find ourselves faced with a pointed renewal of attempt, which is not free from dangers and errors, to fuse Christian meditation with that which is non-Christian.” He goes on to say, “Still others do not hesitate to place that absolute without image or concepts, which is proper to Buddhist theory on the same level as the majesty of God revealed in Christ.”11

Response: This is a misunderstanding of both Christian contemplative teachings and Buddhist meditative disciplines that needs to be corrected through interreligious dialogue. It should be clear from what I have said above that to be free from images and concepts about God is one of the greatest gifts of grace to the Christian contemplative. The fact that other contemplative traditions have made similar discoveries should not be disconcerting, but rather a great source of consolation to those of us who hope for a real dialogue of spiritual experience on a deep level.

He says they abandon the Triune God, “in favor of an immersion in the indeterminate abyss of the divinity.” Then he says mixing Christian meditation with Eastern techniques can lead to syncretism (the mixing of religions).

Response: There is not doubt that some practitioners of Zen Buddhism have brought about confusion (Willis Jaeger in Germany) and have opened the door to syncretism. CP needs to be reminded of the risks here. It would be disastrous to throw out the entire history of Christian contemplative prayer, the most ancient interior prayer of generations of monks and nuns and hermits of many nations and races, out of fear of similarities to the ascetic practices of other cultures and religions! The abyss of the divinity is certainly known in the writings of the great Fathers of the Church, such as Gregory of Nyssa and in the monastic writings, many of which are read every day in the Liturgy of the Hours (Office of Readings); no one should be dismayed by these profound teachings, the treasures of our Christian heritage. Of course, there is the question of a misuse of techniques, but again this requires discernment and discretion. In other words, the guidance of a spiritual director is needed. For many Christians, unfortunately, finding a spiritual director who understands the gift of contemplation is nearly impossible. Ten percent of the participants in Buddhist retreats in northern California are Christians who do not wish to become Buddhists, but were unable to find a Christian spiritual guide in their search for the contemplative path.

Is the Vatican II Statement Regarding Non-Christian Religions Misunderstood?

Yes. The documents of Vatican II state “the Catholic Church rejects nothing of what is true and holy in non-Christian religions.”12 The Council Fathers however, were not recommending the practice of eastern prayer techniques. The Hindu view of God is contrary to Christian belief. They do not worship a God who is superior to them. They believe that they become god, like a raindrop into an ocean.

Response: Although this metaphorical expression, “like a raindrop into the ocean”, turns up in some non-Christian writings, it is best understood poetically rather than as an affirmation of philosophical ontology. Actually, some Christian mystics have used similar language in the past. For example, St. Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi spoke of the contemplative soul becoming a flame that is inseparable from union with the divine flame. The vast majority of Hindus most certainly believe God to be superior to humans, and the divine state as something towards which humans should aspire by means of rigorous self-discipline, morality, meditation, and obedience to a spiritual master. Even the pure non-dualists (advaita Vedanta) know that you have to do something to get to that point of opening to the atman-brahamn realization, and many of them believe that this realization requires divine grace. The author needs to talk to real Hindus and to read more deeply in these matters.

By the way, it is not necessary for something to be “true and holy” that it be identical to one or another Christian practice or belief; it is also true that Christian practices have been very diverse over the ages. Even in the early Church, there were controversies about ideas and spiritual practices attested from Ireland to China, from the first century Gnostics to third century charismatics (Tertullian). Also, Hindu devotional practices (saguna bhakti) seem comparable to Christian practices, but in many key ways are not really compatible at all because they are based on the specific form of a particular deity. On the other hand, some Hindu “formless” meditation practices (nirguna bhakti, also known to the Sikhs) are in fact more compatible, precisely because they are “formless” and because the methods of guidance used for students of these approaches are similar to our own methods of spiritual formation.

In my opinion, recollection is the basis of contemplative formation for Christians, and this is found in all contemplative traditions. The culmination of contemplative prayer is union with God. The daily practice of that union is constant self-oblation. It is good to keep it simple.

What Does Fr. Keating Teach About Reaching “Pure Consciousness”?

In his book, Open Mind, Open Heart, Fr. Keating says, “As the Spirit gradually takes more and more charge of your prayer, you may move into pure consciousness, which is an intuition into your True Self.”13 Then, again, speaking of pure consciousness, he says “In that state, there is no consciousness of self. When your ordinary faculties come back again, there may be a sense of peaceful delight.”14

What are Altered Levels of Consciousness and What are the Dangers?

Let us ask Maharashi Yogi, the guru who introduced TM to America. Fr. Finbarr Flanagan writes in his article “TM’s founder, the Maharashi Yogi, claims that the regular practice of TM leads beyond the ordinary experience of waking, sleeping, and dreaming to a fourth state of consciousness called “simple awareness.” Constant practice leads to cosmic consciousness, then god-consciousness, and finally “unity consciousness.”15 The fourth state in other books is also referred to as pure-consciousness. People who have reached these altered levels of consciousness (ALC’s) describe them as a pleasant trance-like state. Cardinal Ratzinger says, in regard to ALC’s, that these can be pleasant experiences only. He states, “Some physical exercises automatically produce a feeling of quiet and relaxation, pleasing sensations, perhaps even phenomena of light and warmth, which resemble spiritual well-being.

To take such feelings for the authentic consolations of the Holy Spirit would be a totally erroneous way of conceiving the spiritual life. Giving them a symbolic significance typical of the mystical experience, when the moral condition of the person does not correspond to such experience, would represent a kind of mental schizophrenia which could also lead to psychic disturbance and, at times, to moral deviations.”16

Response: What the Cardinal is saying is perfectly true. All the great traditions, East and West, know that the meditator can be distracted by pleasurable sensations, locutions, visions, and the like. This is why you need a spiritual director who helps with spiritual discernment. Trance states are known to be dangerous; the Dalai Lama warned the people at the World Community for Christian Meditation about trance states leading to spiritual torpor and inattention. Some altered states of consciousness can fall into the category of trance. Real contemplative awareness is not a trance state. Some features of the prayer of quiet, such as bodily stillness and lack of unwanted thoughts, resemble some forms of trance, but the mental alertness is heightened, not diminished. There are also some states that involve a loss of ordinary consciousness, but these are risky and require discernment. Falling asleep during discursive meditation is not contemplative prayer, but it may be the result of a deep sense of fatigue, by which God gently heals the person. However, sleep or drowsiness should not be the habitual state of the practitioner of contemplative prayer. There is in fact a kind of unconsciousness described by the Spanish Carmelites on the basis of their wide experience in guiding souls. This state seems to occur very rarely, and it may be an imperfect form of the prayer of quiet.

It is very important to recall that emotions, sensations, suspension of consciousness, “slain in the Spirit,” and other phenomena are common among Pentecostals and Charismatic Christians. Often these believers become powerfully attached to such experiences. Afterwards, they have a hard time adjusting to daily life and normal parish liturgical celebrations. They behave like addicts, eager for religious emotions. I have seen persons exhibiting this religious pathology who began to mimic bipolar syndrome. True contemplatives are at peace with the ordinary things of life, including religious life. It is also admitted by traditional Pentecostals that their experience of the Holy Spirit is analogous to the trance states of those cultures where shamanism is practiced. Once again we ask: is the pot calling the kettle black?

In the life of prayer, we are looking for persons to move from rigid thinking and behaving towards inner freedom, firm commitments, and moral wholeness. Being healthy in mind and body is a feature of most contemplatives. True, there are contemplatives who struggle virtuously with illness. It is interesting to note the quality of a true contemplative’s response to suffering. Their response is quite different from people who are attached to worldly pleasures, but theirs is also different from those who are attached to spiritual pleasures. In any case, pleasurable or heightened emotions are most certainly not a sure sign of the working of the Holy Spirit, nor are pseudo-shamanic trance states as observed in some fundamentalist cults.

Clare Merkle, a former New Age healer and yoga practitioner, has been appearing on EWTN network (Mother Angelica’s network) on the program, “Living His Life Abundantly” Now converted, it took her five years to be freed from the effects on her involvement in New Age. She gives this warning: “When we open ourselves up to foreign religious practices that have ties to the occult, we open ourselves up to the demonic.” (Hinduism and Buddhism have ties to the occult because they tap into spiritual power that is not from the Holy Spirit.) On her website, The Cross and the Veil, she exposes CP as New Age. (See crossveil.org.) She said that going into ALC’s can be dangerous because they can lead to out-of-the body experiences or hallucinations. She said some people cannot come out of them. In Fr. Keating’s book, Open Mind, Open Heart, p. 120, one of his followers commented that he had a hard time coming out of an ALC during Mass and could not concentrate. Fr. Keating told him, “That is a nice problem to have.” Fr. Amorth, who is the Vatican exorcist, says “Yoga, Zen, and TM are unacceptable to Christians. Often these apparently innocent practices can bring about hallucinations and schizophrenic conditions.”17

Response: Here again, we have an incredibly prejudicial and crude pastiche of unsupported arguments. This paragraph does, however, help us understand something of the author and her sources. There is a troubled circle of people who have a need to write polemics about anything that resembles the things that deluded them in an earlier phase of life. Those who do such things, for all their good intentions, are manifesting another form of spiritual materialism. This paragraph amounts to a form of hate speech. Many of these sentiments are coming from the anti-cult movement fostered by fundamentalist attacks on non-Christian religions, which-for them- include Catholicism! Unfortunately, the late Fr. Amorth, who was the exorcist for the Diocese of Rome (not the Vatican), was not an expert on Eastern religions and should not be cited as a reliable source. He dedicated his life to helping confused and deeply troubled people. What they told him should not be held up as anything other than subjective experiences of spiritual pathology. As for hallucinations and so forth, these can be found in abundance just about anywhere in the world of religious enthusiasm. Hallucinations, apparitions, locutions, and visions have nothing whatsoever to do with real contemplative prayer, CP, or monastic tradition. It is a well-known fact that people with schizoid tendencies are drawn to religious practices; but you cannot blame religion as being a cause of the disease imprecisely called schizophrenia. The “voices” that schizophrenics hear can be clearly distinguished from real interior “locutions” by the process of spiritual discernment, as St. John of the Cross indicates. I again find myself astonished that the editors of a pastoral periodical would not have tried to do some damage control on this unfortunate text.

Can Centering Prayer Lead to a Hindu View of God?

Yes, it can. For example, Fr. Keating studied the eastern religions, and wanted to “devise an approach to Christian spirituality that would be comparable to the methods of the East.”18 However, somewhere in his studies, he appears to have succumbed to the Hindu view of God. Throughout his book, Open Mind, Open Heart, he refers to God as the Ultimate Mystery, the Ultimate Presence, and the Source.