An odd thing happened to me the night before the mass murder at Sandy Hook Elementary School.

My wife and I had watched a recorded episode of Parenthood in which Kristina, a wife and mother, very nearly passes away in a hospital. The recording she had made for her children, in the event of her death, was powerful, especially for the grief and anger Kristina showed when she addressed the newborn baby girl who would not remember her mother. So mortality was on my mind when I put my four-year-old daughter to bed.

I have always found the thought of death…well, I suppose the most literal word would be revolting. But even that’s not quite right, because it’s not death precisely but death’s promise that I find so revolting. We have our faiths and philosophies, yet whatever we believe, we must confess that death presents us with the possibility that we will simply be extinguished. Poof. Gone. Our consciousness, our personhood, our joys and sorrows, our creativity and our dreams — could simply evanesce.

As Heidegger wrote, it is not merely that “death comes for everyone.” Abstractions are ways of deflecting the impending personal reality of death. Death is coming for me. Coming soon. It will be here in a blink. And as Pascal understood, we fill our lives with distractions — with busyness, with gossip, with petty arguments, with superficial diversions — in part to turn our attention from the specter of death that hovers always in the corner of every room. In the very best of circumstances, someday soon you will look up from your deathbed into the grieving faces of your dearest loves ones. Your heart will slow, your hand will fall, your lungs will release, and your eyes will grow dim. If death promises true, then when your eyes shut, they will never open again. You will never see or hear or think or remember or hope or desire or grieve or love anything or anyone ever again. And that’s in the best of circumstances — to say nothing of dying in agony, in panic, alone.

I found death’s threat terrifying when I was young. I found it revolting as I began to build a family. That is to say, it felt not only frightening; it felt wrong. When I was a child with too much energy left at the end of the day, I would lie in bed for hours and stare at the ceiling and feel the terror of death. Shortly after I married, I would lie in bed and imagine a five-foot wall of earth separating my casket from my wife’s, and every scrap of my consciousness was filled with the burning sensation of the radical offensiveness of death. The prospect of eternal separation was unbearable.

Yet what happened that night, the night before the massacre, was that the thought of mortality settled upon my daughter. I don’t know how death will find my daughters, but find them it will. The light of their eyes will grow dim. All the joy and playfulness, the rapturous love and soaring dreams, the boundless creativity, the exquisite light in their eyes, the spirit that shines forth in everything they do — will disappear. As I pondered that, it was not my death that frightened me, or my wife’s death that I found so offensive. It was death itself, death’s promise of permanency. Such unbelievably beautiful creatures, such wellsprings of joy and live, should not be forever extinguished.

Yet what happened that night, the night before the massacre, was that the thought of mortality settled upon my daughter. I don’t know how death will find my daughters, but find them it will. The light of their eyes will grow dim. All the joy and playfulness, the rapturous love and soaring dreams, the boundless creativity, the exquisite light in their eyes, the spirit that shines forth in everything they do — will disappear. As I pondered that, it was not my death that frightened me, or my wife’s death that I found so offensive. It was death itself, death’s promise of permanency. Such unbelievably beautiful creatures, such wellsprings of joy and live, should not be forever extinguished.

My atheist friends will say: That’s just the reality, so deal with it. The anguish you feel at the thought of your child’s death is “nothing more than” a genetic mutation that made its progeny more likely to survive.

But that’s not what I believe. I believe in God. In fact — and I say this as a philosopher thoroughly familiar with all the arguments to the contrary — I think the existence of a Creator is obvious to the open-minded and only denied with great effort. That’s a topic for another time. But while I believe that God generally works his will through the created order and the natural processes he has ordained, including evolutionary processes, I reject the insistence that all things must be reducible to natural causation and I certainly reject the “nothing more than” of the atheist materialist.

When I imagine the death of my daughter, if I can be given a little poetic license, it feels like some kind of leviathan rises up from the stillest depths of my soul — rises up, surges toward the surface and roars NO. And whatever natural process might explain the grief of a bereaved parent, or the horror of a parent contemplating the death of his child, it’s also much more than a chemical reaction. It’s a moral, rational and spiritual response to the world. It’s a revolt against death. A revolt against the dark, never-more promise of death, against the threat that when death reaches its cold fingers around our throats it will pull us down to the grave and hold us captive away from everything and everyone we have ever loved — even God.

The most fundamental metaphor God has given us for our relationship is the metaphor of the parent and the child. And if I feel this terrible revolt against death’s promise of permanency, I believe God feels it too. God brought us forth like a father brings forth children. In our best and truest moments as parents, we reflect just a little of the heart of God. And if my fatherly heart feels agony at the prospect of an everlasting separation from my children, if it cannot contemplate the death of so much joy and creativity and love without feeling a rising, roaring “NO!” de profundis, I believe the Father of fathers feels it infinitely more.

Which is why he defeated death.

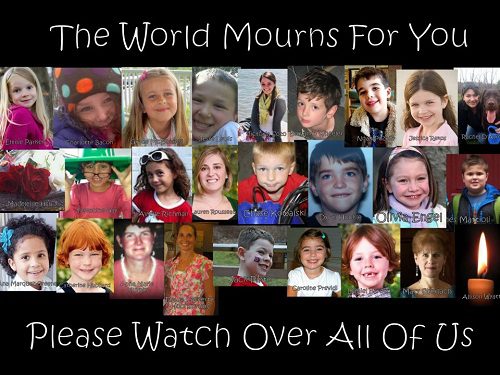

Americans are moved by this mass murder even more than other cases, not only because of the number of the slain but because they were not movie-goers or even college students but little children. Americans are grieving as parents. We grieve because we imagine our own children’s or grandchildren’s little bodies pumped full of bullets like the lost children of Sandy Hook. And we grieve because we know the headline in my local paper this morning — “Message to survivors: You’re safe” — is simply not true. In this life, it never is.

We want to act, and we should. But there will be no sanctuary in changing policies or programs or even culture. We may reduce the frequency of these kinds of events. But we live in an age in which the ancient evil of the human heart will invariably find the modern means of ripping it apart.

Our ultimate sanctuary is in our ultimate hope that we shall be reunited on that far shore. I have long believed that God delights in my daughters even more than I do. I’ve long believed that he loves them with a love far greater than any love I can imagine. And so I also believe that God hates, even more than I do, the thought that they should cease to be, that they should be separated from him forever. I believe that God feels the same “NO!” that I do, and he hated death’s promise of permanency with such enormous intensity that he went to the cross to make death a liar — to steal its “victory,” so that death could bring us to him instead of taking us away.

That’s what I feel when I look at these images of the lost children of Sandy Hook. The pain is immense. The questions are unanswerable. But in the last analysis, they are not lost children at all. I cannot believe that death is stronger than the love of God. I cannot believe that God would craft such extraordinary lights only to watch them be extinguished. I cannot believe that a love so immeasurable and eternal would simply allow them to vanish. Love is stronger than death, and Love has stolen its sting.

So I live in the hope that they are found, that the Father of fathers who loves them more than any human father ever could has embraced them and welcomed them into a new home where they will never be harmed again. As Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 15:54:

“When the perishable has been clothed with the imperishable, and the mortal with immortality, then the saying that is written will come true: ‘Death has been swallowed up in victory.'”