Here’s one of my favorite Solstice songs — Dar Williams’ “The Christians and the Pagans.” It’s a gentle, sweetly funny holiday story, and it paints a nice picture of robust religious pluralism.

We’re different people with different beliefs. We’re also kin and neighbors. And we all like pie. The only thing that stops us from living together is our tendency to lose our minds out of fear and cowardice, and we might perhaps choose not to do that.

There’s a lovely moment in the last verse when the uncle decides to call the brother he hasn’t spoken to in a long time. “It’s Christmas,” he says. He states this as a greeting, a request, an explanation, an argument, an apology. And it works as all of those.

That phrase gets used a lot in all of those ways this time of year. “It’s Christmas,” we say, and the appeal has a strange power to it, as though we’ve just played a trump card that the other person is obliged to recognize.

I don’t think the power of that is strictly sectarian. It’s clearly related to the sectarian Christian holiday of Christmas, and from the way that Christianity has dominated and shaped our culture. But the appeal we’re making when we say “It’s Christmas” doesn’t derive from that, exactly. That’s why it tends to be just as compelling even when it’s made to someone who doesn’t share any particularly Christian notions of Christmas as a sectarian holy day (and also why it’s sometimes not compelling even when it’s made to someone who does).

“But please, it’s Christmas” isn’t so much about the birth of Jesus as it is about us. It’s a reminder that we have, collectively, agreed that this particular time of the year should be different — should be better — than the rest of the year. We have, collectively, agreed that we can and will be different and better, at least for a bit, at this particular time of the year.

Yes, it’s certainly true that one reason our culture associates this annual special dispensation with this particular part of the year is due to the timing of a sectarian holiday, but the need for such a period each year seems broader and deeper than that.

Every Christmas, Christians like to remind everyone that “Jesus is the reason for the season.” Well, yes, obviously. But also not really, or at least not entirely. (Or, I should say, wearing my theologian’s hat, not in quite the way you might think.)

“Jesus is the reason for the season” doesn’t explain “the season” when it comes to Christians because we Christians are supposed to be taking Jesus this seriously all the time. The stuff he taught and showed and commanded wasn’t supposed to just apply to one brief “season.” The Sermon on the Mount doesn’t include some fine print suggesting that it can be ignored for 11 months out of every year.

And it doesn’t explain why “the season” seems compelling even for people for whom Jesus is not a particularly relevant and compelling figure. “Come on, it’s Christmas” works as a deus ex machina ending to a silly story like Christmas Vacation because we recognize that “the season” involves some kind of something that tugs at even people like the Griswolds, or the selfish boss played by Brian Doyle Murray, or the SWAT team raiding the house — people who have no particular affection for or understanding of anything to do with Jesus.

The reason for the season, I think, is that we all recognize that most of the time the world is not as good as we’d like it to be, and that most of the time we are not as good as we’d like ourselves to be. But maybe, if only for a little bit at the tail-end of the year, we could all agree to just act as if we were better people living in a better world.

So “the season” is partly just a conceit, just a pretense or a game. But we all feel the need or the desire to play along with it because we could all use a break from the world and from ourselves and from the awful way we accept or allow things to work most of the time for most of every year.

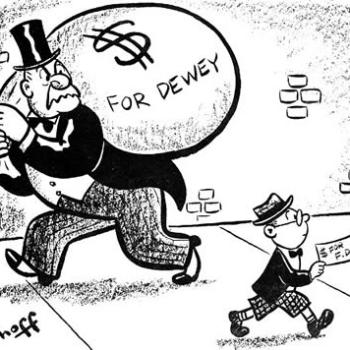

“You can’t lay off those workers now,” we say, “It’s Christmas.” That’s both a lovely and a horrifying argument.

What it’s really saying, in part, is that “Yes, fine, during most of the year it’s perfectly acceptable to put profit-chasing and dividend-boosting ahead of human decency. During most of the year, it’s not unusual or impermissible to be callously cruel, to destroy livelihoods and families, to treat others as tools and objects and stepping stones for one’s own acquisitive ambitions. That’s just the way the world works and no one will stop you from doing that during most of the year. But it’s Christmas. This isn’t most of the year. This is the one little slice of the calendar during which we’ve all agreed, temporarily, to act like we’re not all back-stabbing assholes in a Hobbesian war of all against all. ‘Tis the season in which we all briefly practice just barely enough basic decency that we can almost manage to live with ourselves during the rest of the year when we don’t. Please play along with the illusion that we might in any way possibly be better than that and put off devastating all these families until January.”

It’s an odd arrangement. We seem to be conceding something about ourselves and our lives together. Either we’re admitting that we’re actually capable of treating each other and ourselves much better than we do most of the time, or else we’re admitting that we’re not, and that this little season of respite and forced decency we muster up at the end of every year is just an illusion and the best that we can expect of ourselves and of one another.

Neither admission is particularly flattering, but I prefer the former.

Anyway, have a blessed solstice. Well done, well done everyone. We’re half-way out of the dark.