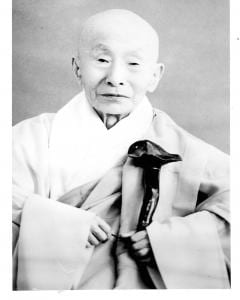

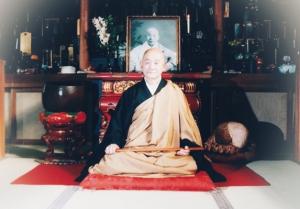

When I was training at Bukkokuji Zen Monastery in Obama, Japan, on the twelfth day of every month, we all took a short walk around the bluff to a small hermitage that lay a short distance outside the wall of our neighboring monastery, Hosshinji, to perform a memorial ceremony at the retirement home of the late Harada Daiun Sogaku (大雲祖岳, Great Cloud Ancestral Huge Mountain, October 13, 1871 – December 12, 1961). The hermitage was a place of lingering radiance. The teacher under whom we trained at Bukkokuji, Harada Tangen Rōshi (1924-2018), was the last and youngest of Harada Rōshi’s fourteen successors, highly revered his late teacher. In fact, a near life-sized portrait (see below) of Harada Rōshi sat behind Tangen Rōshi in his dokusan room.

In this post, I’ll sketch the life of Harada Rōshi, emphasize his role in working with women and lay people, and touch on a few of the controversies that continue today, specifically, whether he received Rinzai transmission, his pre-war and wartime support for fascism, his powerful legacy and the danger of having many successors. I’ve also included some videos related to Harada Rōshi below, as well as links and footnotes with other resources.

The Life of Harada Daiun Sogaku

Let’s begin with the end. Here is his death poem:

For forty years I’ve been selling water

By the bank of a river.

Ho, ho!

My labors have been wholly without merit.

Forty years of selling water by the river, and about fifty years before that gathering water in a wicker basket. Ho, ho!

Harada Rōshi began his monk life early, at age seven, in the same Bukkokuji that I mentioned above. After his Sōtō transmission, he still agonized over the great matter of birth and death, so he sent letters to several Buddhist leaders “…[asking] for a rock bottom answer to the question of life and death: When a human being dies, does he vanish like the clouds and mist, or is there a life after death?” (1)

Only Shaku Sōen Rōshi’s response impressed him:

“If you experience kenshō, you can clear up that little problem before you sit down to breakfast. Both kōans, ‘What is the sound of one hand clapping? ‘and … ‘If all things are innately pure, then how is it that the mountains, rivers, and the great earth suddenly arise?’ are good. If you clearly penetrate either of these koan, your problem will promptly be settled.” (2)

Harada Rōshi then began a twenty year process of training with Rinzai teachers, primarily at Shogenji and Nanzenji. Here is how Harada Rōshi summarized his process of clearing up his “little problem:”

“I was able to hear ‘the sound of one hand clapping.’ That is to say that upon attaining kenshō, I really had deep peace of mind for the first time. As anyone who has had the experience knows, a very special joy accompanies that first kenshō, and in that joy I went off to myself and danced a little jig. But after a month or two, even that experience became doubtful, and I plunged into a deeper anguish than ever. Once again I threw myself into practice. Memories of things like sitting in the snow and doing zazen stark naked in a bamboo grove swarming with mosquitos come from this period. My second kenshō experience may sound a little distasteful. One morning while I was on a long begging trip, an old woman happened to urinate in the toilet beside a farmhouse gate as I passed. When I saw the frothing urine I had satori.” (3)

But he wasn’t done training. Eventually, he practiced under the great Rinzai master, Dōkutan Sosan Rōshi (a.k.a. Dōkutan Toyota, 1840-1917). Harada Rōshi said this about Dōkutan Rōshi:

“Dōkutan Rōshi was an outstanding training master, endowed with both the power of buddhadharma and with moral excellence. I am truly fortunate to have been able to practice under such a highly respected teacher…. Dōkutan Rōshi trained to this extent despite a weak constitution from childhood. He always spoke very softly, but when this rōshi would scold me, in a voice one could just barely catch, a cold shiver of sweat would break out of my armpits. I had been hauled roughly over the coals by other masters before and remained relatively cool, but while Dōkutan Rōshi’s words were similar or equal, his strength of character added force. I learned from him that strength of character alone can move [people].

And the following passage from Three Pillars of Zen summarizes Harada Rōshi’s process training with Dōkutan Rōshi:

“He was accepted by Dōkutan as a disciple, and for the next two years came daily for koan practice and private instructions while living with a friend in Kyōtō whom he assisted with the affairs of his temple. At the end of two years Dōkutan Rōshi, impressed with his disciple`s uncommon intelligence, ardor, and thirst for Truth, offered to make him his personal attendant. Though now almost forty, Sogaku Harada accepted this signal honor with alacrity and went to live at Nanzenji. There he applied himself intensively to zazen and completed all the koans, at last opening his Mind’s eye fully and receiving inka from Dōkutan Rōshi.” (4)

There are a couple points to highlight here. First, a Sōtō monk was accepted into one of the main Rinzai training centers as the teacher’s attendant. This would be against the rules for both Sōtō and Rinzai today. If a Sōtō monk wants to enter a Rinzai training center, they first need to be reordained. I don’t know if the rules have changed or if the case of Harada Rōshi was exceptional.

In any case, Harada Dauin Rōshi lived an exceptional life of Zen awakening and training.

Controversy surrounding inka shōmei

The second point that stands out above is the issue of Harada Rōshi receiving inka shōmei (印可証明), literally, “evidence of the mark,” from Toyota Dokutan Rōshi. Meido Moore explains that a qualified teacher in Rinzai Zen, “…means not only that the teacher has completed the requisite training and received inka shōmei, the seal of lineage inheritance from a legitimate master; more importantly, it means that the teacher manifests some degree of embodied realization, ideally including the spontaneous, extraordinary means of guiding students.” (5)

So for a Rinzai master to fully authorize a Sōtō monk is most unusual and remains controversial to this day.

James Ford Rōshi lays out the controversy like this: “There is debate within the Zen community as to whether he actually received dharma transmission from Dōkutan Rōshi. I was told by Maezumi Rōshi that while Dōkutan Rōshi considered Harada Rōshi to have completed all necessary training with him to be an independent master of the koan way, there was no formal transmission. In that time and place such a formal recognition would have also had Harada leave the Sōtō school, something that he had no desire to do.” (6)

Given that Yasutani Rōshi, one of Maezumi Rōshi’s teachers, had publicly stated (see below), that Toyota Dōkutan Rōshi had indeed given inka shōmei to Harada Rōshi, Maezumi Rōshi’s statement is puzzling. Perhaps for it to be “formal transmission” in Maezumi Rōshi’s eyes, it would have needed to be a “public transmission.”

On the other hand, Yasutani Rōshi, Harada Rōshi’s most prolific direct successor, wrote that Harada Rōshi had told him,

“When I received inka (completion of examination in dokusan) from Dōkutan Rōshi, he said to me, ‘The Sōtō sect is a large religious denomination. If you say that it has no true teachers, and that you went and got dharma transmission from a Rinzai master, it would affect the Sōtō sect’s reputation. So keep this secret and say that you got dharma transmission from an appropriate person within the Sōtō sect….’ I was truly grateful for these words. And so I would not indiscreetly divulge the fact that I was given transmission by Dōkutan Rōshi.”

Yasutani first published about this in Japan in in the early 1960’s, shortly after Harada Daiun Rōshi had died, in “… A Soliloquy on the Five Modes, Threefold Return, Three Unified Pure Precepts, and Ten Grave Precepts, “Geneological Chart of the Buddhist Ancestors’ True Dharma Transmission.” Harada Sogaku’s dharma lineage records him as being a dharma successor of seventh-generation Hakuin descendant Kōgen Shitsu Dokutan Rōshi…” (7)

In my view, in the Japanese and monastic culture in which Harada Daiun Rōshi lived, it seems unlikely that he would have given something that he hadn’t received. He clearly felt confident teaching kōan widely and giving inka shōmei to fourteen students. This suggests to me that he had likely received inka shōmei from Toyota Dokutan Rōshi, as the statement from Yasutani Rōshi attests. If so, it is an example of Harada Rōshi navigating the Japanese monastic cultural waters with skill. He acted like he had received inka shōmei from a Rinzai master while never saying so (as far as I know) in a public venue. Such behavior limited the shame of the Sōtō sect, while exercising his capacity to facilitate the awakening of many students.

Teaching career

According to Harada Rōshi, “In my youth, I formulated a rough schedule for my life. I would devote myself to practice and study until I turned forty. Then from forty to sixty, I would work for others, giving religious instruction. From sixty on, I would continue to make every effort within my power. However, when the scheduled age of forty came around, it looked as though I had no alternative but to accept a teaching post in the university I had been attending. I taught at Komazawa University for twelve years – until I realized that it was far more important to train Zen monks than to follow the teaching profession. So I started Hosshinji Monastery, and I have been there ever since….” (8)

The sesshin led by Harada Rōshi at Hosshinji were famously intense. The kyōsaku was used frequently and with intensity. Phillip Kapleau, one of the first Westerns to train extensively in Japan, is said to have sewn a piece of leather in the shoulder of his koromo to mute the effect of the persistent use of the kyosaku. When his “accommodation” was discovered, he was not treated kindly.

During Rōhatsu Sesshin particularly, participants would aim to sit through the night every night, and if sleep threatened to overcome them, some would go the pond near the main gate, cut a hole in the ice, and jump in.

In addition to the many monks training at Hosshinjin, many lay people, both women and men, from all over world came to train with Harada Rōshi. During Harada Rōshi’s forty years at Hosshinji, he also travelled throughout Japan, frequently offering sesshin. His lay students included the head of Mitsubishi, Iwasaki, who realized kenshō, and his daughter, Yaeko Iwasaki. Although frequently sick with tuberculosis and bedridden, Yaeko passed through kenshō to great enlightenment in a period of a few days, just before she died at age twenty-five. See Yaeko Iwasaki´s Enlightenment Letters to Harada-Rōshi and his Comments for a jubilant and heart wrenching account of her awakenings and death, including comments by Harada Rōshi that give us some sense him and of how he worked with students.

Also, click here for “No Place Not Known: An Audacious Awakening,” a talk about Yaeko’s awakening process with Harada Rōshi.

Harada Rōshi also gave inka shōmei to Nagasawa Sozen Rōshi (1880-1971), a Zen nun. Nagasawa Rōshi established the Tokyo Center for Nun’s Training and led many women to awakening. A Collection of Meditation Experiences (untranslated) recounts the awakening stories of sixty women and two of these stories are translated in Buddhism in Practice, ed., Donald S. Lopez, “Awakening Stories of Zen Buddhist Women,” by Sallie King. Sallie King writes,

“Nagasawa Rōshi was in her time perhaps the only nun directing a Japanese Zen nunnery and practice center and holding meditation retreats without the supervision of a male Zen master…. It is noteworthy that Nagasawa Rōshi is depicted as training her disciples in the same manner as other teachers in her line. Though a number of contemporary Western feminist Buddhists have criticized aspects of Zen training as “macho,” and some modern Zen masters have dropped some such practices, Nagasawa Rōshi seems to employ them all. She is depicted as being quite stern and even fierce with her disciples before they make a breakthrough in their practice, shouting at them and abruptly ringing them out of the interview room with her dismissal bell; she relies heavily on a koan practice in which the disciple aggressively assaults the ego, suffering a roller-coaster ride of blissful highs and despairing lows in the process; and she uses the ‘encouragement stick,’ a flat hardwood stick with which meditators may be slapped on the shoulders during prolonged meditation sessions to help them call up energy for their practice (it functions much like cold water splashed in the face and is not a punishment). This severity is what Zen calls ‘grandmotherly kindness’: the teacher’s aid to the student working to free herself from the limitations of ego. The atmosphere of the meditation retreats is portrayed as taut and austere; Nagasawa Rōshi herself is described as possessing exalted experience and, though hard and demanding before a disciple makes a breakthrough, warm and gentle when the breakthrough is achieved. It is clear that her students deeply respect her and are grateful to her. All this is classic Japanese Zen. Thus, while Nagasawa Rōshi does represent for her time a female incursion into a male world, she makes no changes in behavior within that world other than the significant change of inviting other women into it.” (9)

An incredible teacher. Unfortunately, Nagasawa Rōshi’s lineage seems to have died out.

One aspect of the Harada Rōshi’s lingering radiance is the wholehearted devotion awakening, free from categories, still apparent in his surviving lineage.

Controversy about wartime support for fascism

The lingering radiance of Harada Rōshi includes a lingering shadow.

James Ford Rōshi writes, “Harada Roshi was a prominent figure within the Sōtō church. And he has been criticized, and I think justly, for his fervent support of Japanese nationalism in the years running up to and through the Second World War. A caution, I feel, for all of us as we necessarily engage the cultures within which we live.” (10)

Here is an example of Harada Rōshi’s wartime views:

“The spirit of Japan is the Great Way of the [Shinto] gods. It is the substance of the universe, the essence of the Truth. The Japanese people are a chosen people whose mission is to control the world. The sword which kills is also the sword which gives life. Comments opposing war are the foolish opinions of those who can only see one aspect of things and not the whole. Politics conducted on the basis of a constitution are premature, and therefore fascist politics should be implemented for the next ten years …. Similarly, education makes for shallow, cosmopolitan-minded persons. All of the people of this country should do Zen. That is to say, they should all awake to the Great Way of the Gods. This is Mahayana Zen.” (12)

While I was training at Bukkokuji, on the four and nine days we had a lighter schedule with time for personal cleaning. We would “sleep in” until 5:00am, practice zazen, do liturgy, have breakfast, and then have quasi-formal tea with Tangen Rōshi. After we all enjoyed some matcha, Rōshi would give a short talk and usually take questions. On one such day, his long-time translator, Belinda Ataway, asked about Harada Rōshi’s books during the war. “I’ve been reading them,” she said, “and am having a hard time understanding how an enlightened teacher could hold such views.”

Tangen Rōshi said that he also had held the view that the emperor was god and supported the military regime, hoping to die for Japan. “We believed that Americans were devils,” he told us, “and that saving the Mahayana was up to us. After the war, we discovered that we’d been completely duped so we changed our views.”

He said that Harada Rōshi’s support for Western students was part of his repayment for his previous wrong doing. And that Harada Rōshi had seen from political errors in pre-war and wartime Japan how he much he still needed to work on himself.

Legacy

Harada Daiun Rōshi impacts on global Zen Buddhism continue to unfold almost sixty years after his death. He not only brought kōan practice and awakening back into Sōtō Zen, his reformed curriculum, excising the aspects that required post-doctorate Chinese and Japanese language skills, made kōan training accessible to non-Japanese speaking students. His emphasis on lay training, as well as the full inclusion of women, broke cultural barriers and made Zen relevant and accessible to modern practitioners.

Of his fourteen successors, the successor who has likewise profoundly impacted Zen today is the least monastic among them, Yasutani Rōshi. The source of the practice and awakening in the White Plum, Diamond Sangha, Sanbo Zen, Kapleau lineage, and many others (including the Aitken-Tarrant-Ford branch I represent) is Harada Rōshi. The website Harada-Yasutani School of Zen Buddhism and its Teachers lists about 400 teachers who have received transmission in the Harada-Yasutani lineage, some teachers now eight generations removed from the old teacher. About half of these teachers appear to be women, and almost all are lay people or nonmonastic Zen priests. (12)

And, yet, it all isn’t light and kenshō. Problems with rigor and integrity have come with the rapid growth in authorized teachers. In some lines descended through Harada Daiun Rōshi, “passing” kōans, including the initial kōan, has been reduced to dharma play without kenshō. One student told me that they passed mu by saying that mu was “everything,” knowingly lacking any experience of being mu or seeing mu. Another student told me that in a line also descended from Harada Rōshi, that they were instructed to skip mu because the teacher felt that it was too difficult. Another student said they had worked through the whole of the Harada-Yasutani curriculum, but when I tested with the first mu checking question, the student was at a loss.

Nevertheless, the radiance of Harada Rōshi’s practice, awakening, and teaching linger still. Although not without shade and shadow, truly, I’ve found, this radiance can be a light in our troubled times.

(1) “My Life in Zen Temples,” at https://terebess.hu/zen/mesterek/harada.html

(2) Ibid.

(3) Ibid.

(4) The Three Pillars of Zen, pp. 305-306.

(5) The Rinzai Way of Zen, Meido Moore, p. 155.

(6) See “The Great Cloud Dies: Recalling Zen Master Daiun Sogaku Harada,” by James Myoun Ford Rōshi here.

(7) Sanbo Zen Newsletter, Kyosho 370.

(8) “My Life in Zen Temples,” at https://terebess.hu/zen/mesterek/harada.html

(9) In Buddhism in Practice, ed., Donald S. Lopez, “Awakening Stories of Zen Buddhist Women,” by Sallie King (Princeton Readings in Religions) (p. 397).

(10) See Ford blog post above.

(11) Zen at War, by Victoria, Brian Daizen, p. 137.

(12) Harada-Yasutani School of Zen Buddhism and its Teachers. “400 successors” is a “give or take” number. Some listed on the linked site have died, some listed aren’t authorized, and some with full authorization are not included, probably because they have not asked to be.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with Vine of Obstacles Zen, an online training group. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, was published in 2021 (Shambhala). His third book, Going Through the Mystery’s One Hundred Questions, is now available. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi.