Some people have the impression that Christian faith requires the rejection of scientific discoveries and theories. This idea is exacerbated by the arguments of some Christians today who reject a wide variety of scientific positions deemed incompatible with scripture; these often concern the age of the earth and evolution. These Christians interpret the scriptures about creation (Genesis 1-2) and the genealogies and ages of the first humans (Genesis 5) literally. Most Christians, however, have a broader view of the events described in scripture and recognize that the biblical account is not meant to give a scientific description but a spiritual one. They would argue that science attempts to answer questions about how things are, but not about why things are, which is the realm of religion.

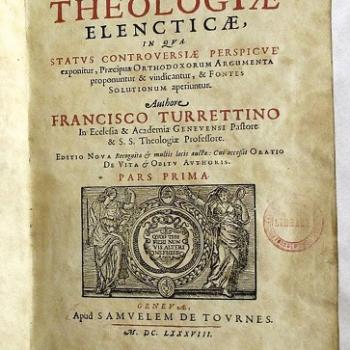

The apparent conflict is relatively new in the history of religion. Most ancient natural philosophers were religious; many great medieval Islamic scholars blended their faith and their scientific achievements; and the great luminaries of the European scientific revolution—Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, Brahe, Kepler, Descartes, Pascal, Huygens, and others—were also Christians.

No one disputes the fact that the Church has wrestled with, and sometimes resisted, the implications of certain scientific discoveries. Galileo’s argument about heliocentrism is the best-known example, yet scholars point out that part of the Church’s objection to Galileo was because he insisted that scriptures which talk about an unmoving earth (e.g., Psalm 93.1) should not be interpreted literally. Thus, their objection was not based on science per se but on Church authority and the use of scripture.

These cases, however, are far outweighed by the many examples of faith and science working together. Seventeenth-century chemist Robert Boyle was known for his Christian piety. The “father of modern genetics,” Gregor Mendel, was an Augustinian monk of the 19th-century. Michael Faraday, who discovered electromagnetic theories, was a devout Scottish Christian. The first to suggest the Big Bang theory, George Lemaître, was a 20th-century Catholic priest, mathematician, and professor of physics. These are just a few examples of the compatibility of faith and the practice of science.

Nevertheless, the 1896 publication of A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom by Andrew Dickson White made popular the idea that Christianity has always thwarted the advance of science. Modern historians of both science and religion have rejected White’s scholarship and argue that he constructed this “warfare” narrative for the purposes of purging religion of its dogmatic elements and making possible a more accessible religion of tolerance and morality.

Today, with the noisy exception of a few outspoken atheists and fundamentalist Christians, science and religion comfortably coexist. A 2009 poll of scientists showed that over half of scientists today believe in some supernatural power or personal God. Saint Augustine (354-430) argued that all truth is God’s truth, wherever it is found, and this concept has been affirmed in many Christian circles ever since.

3/23/2021 6:32:40 PM