I’ve been to many a secular conference now where I’ve presented on the topic of “In God We Trust.” Without fail, someone in the audience will bring up the Treaty of Tripoli. I’ve also run across the Treaty of Tripoli in many atheist/secular forums and websites, including here on Patheos. I’m writing today to beseech my fellow secularists with a simple request: please, for the love of god (in the colloquial sense), stop quoting the Treaty of Tripoli.

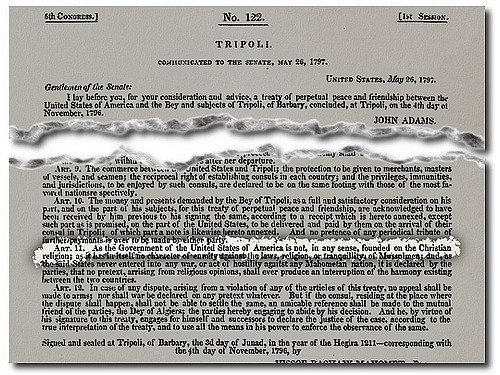

Secularists love to quote the first clause of the first sentence to Article 11 of the 1797 treaty, which reads, “the government of the United States is in no way founded on the Christian religion.” The problem with this is that quote isn’t the entire first sentence – it isn’t even all of the first clause – and it completely takes the Treaty of Tripoli out of its historical context.

First, let’s cover a little history. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the states of North Africa collectively called the Barbary States – Algiers, Morrocco, Tunis, and Tripoli – would raid European shipping in the Mediterranean Sea. To prevent their commercial ships and sailors from being seized, the states of Europe would pay what was essentially protection money to the rulers of the Barbary coast. In 1783, when the American colonies gained their independence, Great Britain stopped paying the protection money for American shipping for obvious reasons.

Enter the Treaty of Tripoli.

In 1797, United States Commissioner Plenipotentiary David Humphreys certified the what would become known as the Treaty of Tripoli, which in its own time was known officially as the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary. Treat of Tripoli is a convenient shorthand. The treaty established commercial and maritime rights for the United States, acted as a sort of peace treaty (though there was no official war), and defined the amount of tribute to be paid by the United States to the Bey of Tripoli. So what does this have to do with atheism and secularism?

As mentioned above, article 11 of the treaty states that the United States government is not founded on the Christian religion. But, as mentioned above, that isn’t the whole story. Here is article 11 in full:

“As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion,-as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen,-and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.”

Article 11 does not establish a historical fact about the United States in particular – which is how most secularists use it – so much as it defines the relationship between the government of the United States and the government of Tripoli. In essence, Article 11 is stating that differing religious opinions shall not be considered a pretext for violating the treaty. It should be noted that the article is careful to point out that the United States had never engaged in any armed conflict with a Muslim nation.

Still, the first clause in Article 11 is attractive to modern secularists because it seems to set a precedent for a religiously-neutral government. Taken completely on its own, I would argue that article 11 does, in fact, establish that the United States is not a Christian government. However, and any respectable academic would agree, you cannot simply look at one piece of evidence to try and establish a historical (or any other) fact. In history, you must look at evidence that is contradictory in order to gain a more precise understanding of context. Take, for example, this 1798 proclamation from President John Adams, who was president when the Treaty of Tripoli was ratified, which states,

“[T]he safety and prosperity of nations ultimately and essentially depend on the protection and the blessing of Almighty God, and the national acknowledgment of this truth is not only an indispensable duty which the people owe to Him, but a duty whose natural influence is favorable to the promotion of that morality and piety without which social happiness can not [sic] exist nor the blessings of a free government be enjoyed.”

Further on in the proclamation – which promoted a national day of humiliation, fasting and prayer – it recommends “that all religious congregations do, with the deepest humility, acknowledge before God the manifold sins and transgressions with which we are justly chargeable as individuals and as a nation, beseeching Him at the same time, of His infinite grace, through the Redeemer of the World, freely to remit all our offenses, and to incline us by His Holy Spirit to that sincere repentance and reformation which may afford us reason to hope for his inestimable favor and heavenly benediction.”

So though it may be true that the United States government did not enforce a specific sect of Christianity, it certainly wasn’t neutral when it came to religious matters. In fact, religion was viewed as necessary to a civil society and the government of the United States, through its executive, was willing to incorporate Christian beliefs and Christian symbolism into its affairs. Taken on its own, this type of proclamation suggests that the United States government is in fact founded on the Christian religion. The government saw pleas to the Almighty through Jesus Christ (aka “Redeemer of the World”) as necessary for the survival and well-being of the nation it governed. But again, that would be taking one piece of historical evidence to make a political point.

A further fact needs to be considered as well: there are multiple Treaties of Tripoli.

In 1801, the 1797 treaty was broken when Tripoli attacked American shipping after the United States refused to pay more tribute. This led to the First Barbary War – immortalized in the Marine Corps hymn lyric “to the shores of Tripoli – which ended with the signing of a second Treaty of Tripoli. This treaty was very similar to the original with a few notable exceptions, the most notable of which is the clause declaring that the United States is “not in any way founded on the Christian Religion” is completely missing. Here is part of Article 14 of the 1805 treaty:

“As the Government of the United States of America, has in itself no character of enmity against the Laws, Religion or Tranquility of Musselmen, and as the said States never have entered into any voluntary war or act of hostility against any Mahometan Nation, except in the defence [sic] of their just rights to freely navigate the High Seas: It is declared by the contracting parties that no pretext arising from Religious Opinions, shall ever produce an interruption of the Harmony existing between the two Nations…”

If the government of the United States was so adamantly not founded on the Christian religion, why so conspicuously leave that clause out when the treaty was rewritten in 1805?

Now none of this is to say that the United States is or isn’t a Christian nation or founded on Christianity. That is a political battle that exists outside the world of late 18th and early 19th century America. So please, I beg you, stop quoting the Treaty of Tripoli. Not only is it not what you think it is, quoting the treaty in the context of the modern secular movement is a complete distortion of the real-world context in which it was written. It is the exact same kind of distortion that religious pseudo-historians like David Barton make when they point to things like “Creator” in the Declaration of Independence and declare that the United States is founded as a Christian nation.

The past is complicated. There existed no black and white view of the world in the 18th century any more than one exists in the 21st. To cherry pick evidence from an obscure 18th-century treaty without considering its context to make a political point is not only ahistorical, but also unbecoming of a movement that prides itself on critical thought, rational inquiry, and following the evidence no matter what the conclusion.