Catholicism provided the perfect veneer to safeguard ancestral indigenous and African spiritual practices. In the Dominican Republic, the way that the people came together to celebrate the Misterios and carry out group rituals was under the cover of a Cofradia or Hermandad. The Cofradias are social groups that all center themselves around upholding Catholic morals, supporting the community through acts of charity and goodness, and working for the social good. A Hermandad, which means “brotherhood,” is often a smaller group of the same nature. In spite of the names both groups are coed.

Cofradias were established by and backed by the Catholic Church. The church also heavily encouraged the participation of all slaves as their way of working to convert slaves to the new religion. Although, technically Hermandades and Cofradias could be formed by any group of people, at first the Catholics only allowed white slave masters to do so. So, there were and are Cofradias and Hermandades that are totally Catholic and not connected in any way to the 21 Divisions. Priests then decided it was important for the slaves to be given time to participate in the activities of the Cofradia. Likewise, the slaves were to not work on the feast days of the patron saints and were to be given time to socialize and spend together.

Quickly noticing how the slaves embrace the saints and their dedication, the priests decided that they should be allowed to open their own Cofradias. Many of the Catholic priests, happy to see the slaves participating, also slowly allowed for African practices to be brought in, thinking it would further encourage conversion. They felt it would be good for the slaves to incorporate a bit of their own culture and “make it theirs,” so to speak. Unknowingly and unwittingly, they ended up helping preserve the Misterios, the very thing they worked so hard to eradicate. Convinced that the slaves were embracing the new religion of Catholicism, they didn’t mind if they brought in a bit of their culture.

However, the way it worked in the Dominican Republic for the African slaves was that often either a family or a group of brujos would band together to form the Cofradia. The Cofradias therefore became the storehouse for the knowledge and traditions of the 21 Divisions. Many of these Cofradias were some of the first establishments of African spiritual practices in the Americas and continue to operate in various parts of the island.

A Cofradia required a group of at least nine individuals with each charged with a task. Cofradias were a highly organized structure as to their governing and activities. They all were dedicated to a specific saint and celebrated the feast of this patron annually. On these dates, a novena or velada was held in honor of the patron saint. A novena is a prayer process that takes place over nine consecutive days.

During veladas, candle vigils were placed near the icon of the patron saint, and various members took turns “watching” the saint by staying up all night long and praying constantly until the ultimate time of the feast. On the feast day, the Cofradia went out with the Catholic church in a procession for the saint. The processions and celebrations of the Cofradias were always accompanied and followed by dances, African drumming, and music.

After all the Catholic rituals had been carried out, the slaves were allowed to relax and socialize. Not understanding the practices of the slaves, their oppressors simply saw them holding a social event while, in actuality, this is when the service to the Misterios would begin. Communal feasting was always also a central activity within this part of the events. The altar, initially set up in honor of the saint, was now laden with food offerings to the Misterios.

The music would encompass both the saints and the Misterios. The drums beat the rhythms of the African ancestors, particularly those of the Kongo, as the dances became the method through which the souls of the servants would ascend into heaven, leaving the body an empty vessel so that the Divine Misterios could descend within them. Now the rum, the sacred drinks, perfumes, and tobaccos could all come out and be employed in service to the Divine.

This is the way the 21 Divisions and the Misterios survived— all right under the eyes of the slave masters. Naturally due to the circumstances, many elements of rituals and ceremonies had to be altered and adapted. Tools used had to be minimal and things that could be utilized right out in the open. The servants of the 21 Divisions learned to perfect their capacity to allow the Misterios to possess them and be able to do great spiritual work with very little accoutrements.

Due to the laws of those times, a white Dominican could go to a slave Cofradia’s event but not vice versa. So the slaves had to be very careful about their activities. They could face an influx of outsiders at any time. What was Catholic and what was Voodoo had to become well enmeshed, undetectable. Many of the Misterios’ Voodoo names and Catholic saints are now synonymous. Some Misterios with lesser followingshave even lost their African names altogether and are only known by their Catholic counterparts.

Common Roots: 21 Divisions and Haitian Vodou

The Tcha Tcha lineage existed on both sides of the island before it was divided between the French and Spanish. Haitian Vodou and Dominican Voodoo thus share the same root. However, each practice evolved differently based on the different European influences. Each practice grew in the manner in which it could survive and thrive. Likewise, there were fewer Indians mixed into the blood on the French side, as by the time the French arrived there were fewer Indians overall. So each type of practice took on influences to varying egrees from the various tribes of the African slaves, Tainos, and Arawaks in the respective areas, alongside of the dominating culture of either French or Spanish. For example, the language of practice in Haiti became Kreyol and in the Dominican Republic Spanish.

Now, because each was evolving in different cultures under different circumstances, the Misterios adapted to the needs of their people and the capacities of the same as they always do. But the essence of the Misterios and the Mystery itself remained the same. You’ll also see that they share many terms and words, although the way they define those terms and the connotations that they carry may be different. Practices are also shared among the two.

So what are the major differences?

As mentioned before, the French didn’t stress conversion to Catholicism as much as the Spanish did. Furthermore, the Haitians were able to liberate themselves from the French much sooner, and a large percentage of the first enslaved Haitians were actually first-generation Africans. Out from under French rule, the Haitians were able to practice their Voodoo more freely. Thus, they were able to retain larger parts of their African cultures and beliefs.

Haitian Vodou retained many more of the aspects of the religions originating in Africa as well. Because its practitioners viewed it as a religion, the mindset and memory of the ancestral ways were more entrenched. Haitian Vodou includes Catholic rituals, but not to the same degree, and they are obviously much more of a veneer. In Haiti it is common for Vodou priests to operate in temples, and in some Haitian temples all Catholic elements have been removed or were never even incorporated.

Dominican Voodoo, on the other hand, became much more magical in orientation. Its value comes less from its religious aspect as from its practicality, the results of its magic, and its pragmatism. Dominican Vodouisants almost always consider themselves Catholics as far as their religion goes and the 21 Divisions as their spiritual practice. In the 21 Divisions, it is the altar room of the brujo that’s the central ceremonial space. There are no temples. This altar room is usually a room in the priest’s own house. While temples do exist, they are way less common.

Catholic rituals and ceremonies are also an integral part of the 21 Divisions and their magic. For many of the Dominican Misterios, the Catholic saint has become intrinsically connected to the Misterio and that never changes. In Haitian Vodou, it is not uncommon for the Misterios’ Catholic counterparts to change from region to region or in fact from temple to temple.

Public and group rituals that were common in African and Indian practices and therefore were retained in the Haitian form of Voodoo are uncommon in the 21 Divisions. Also, whereas the community is central to the Haitian Vodou priest, the brujo of the 21 Divisions most commonly works in private. Another area of difference is the music and drumming. The songs, the drum rhythms, and the dances between the two traditions have diverged.

_______________

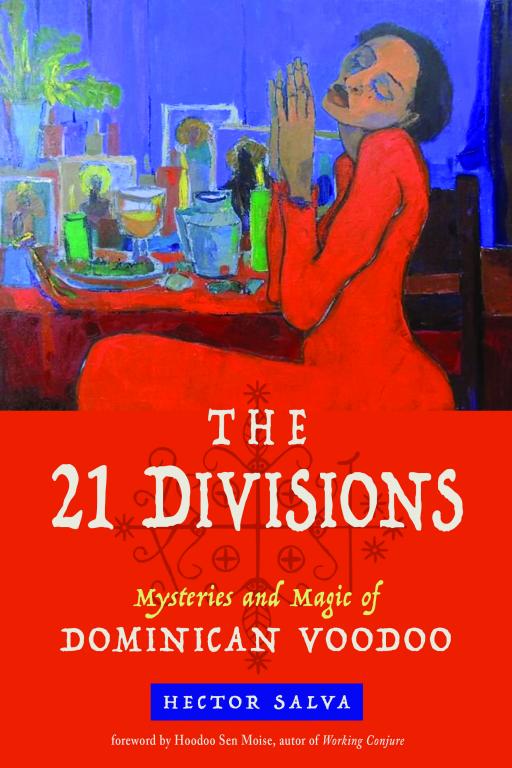

Adapted, and reprinted with permission from Weiser Books, an imprint of Red Wheel/Weiser, The 21 Divisions by Hector Salva is available wherever books and ebooks are sold or directly from the publisher at www.redwheelweiser.com or 800-423-7087