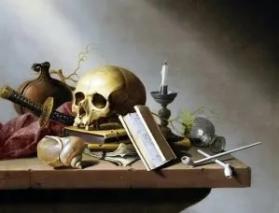

In such a world of placeholders ordered around my will, my hand no longer feels the touch of wood worn smooth by everyday hands when it grasps the banister. I no longer see or smell or touch any thing, only placeholders in their systems, systems given their order and their reality by their relationship to my will. I will be enveloped in solipsism without even knowing it, and the created world will disappear except insofar it is mine. Gratitude must also disappear in a solipsistic world, though its shadows and pretenders may remain.

We see something similar when it comes to the order of the ordinary. It is something that we must be grateful for but that hides a danger. The order into which ordinary things slip silently so as not to obtrude themselves disappears behind my need to get things done, to complete the tasks I've set myself and the jobs my place in the world requires. There is a broad order to my life into which the things I encounter, the work I do, and the people I live with fit. That fit tells me who they are and how I am related to them, and it does so rarely, if at all, requiring me to think about it. I, too, am a placeholder.

As with entities, if that order of the ordinary were not invisible most of the time, I could not get along in the world well. If I didn't have and know my place in various worlds—of work, of the home and family, and so on—I would be a child fumbling about in the world and often in danger if not guarded by someone for whom the broader order is known but invisible. Much of wisdom consists in knowing the order of the ordinary without explicitly knowing that we do. We should be grateful that the larger order of our world usually hides itself though we are able to negotiate it with ease.

Yet sometimes, by disappearing, the order becomes a hidden tyrant, arranging things in the world in a way that gives them values and importance that otherwise I might not assent to. I find myself desiring things because the world induces that desire in me: as a middle-class professor, I discover that I like the same things that other middle-class professors like and want. It is difficult to believe that is mere coincidence, that I and other middle-class professors just happen to like the same things. It is more reasonable to believe that the world is structured in such a way that part of being in the place we hold in the ordinary order includes a propensity to like certain things.

It is difficult to know to what degree my politics and practices as well as my likes and dislikes are informed by the order in which I find myself. And if I ask myself that difficult question, there is no simple way to know whether I've found the answer. People too sure of the answer can be dangerous at worst and annoying at best. I cannot merely reflect myself out of the order and its influence. There is no Archimedean point with which I can leverage myself out of all order.

The answer to the problem, both with ordinary things and, more importantly, with the order of things, is to hold them lightly. Holding them lightly entails allowing for surprise: the surprise the artist makes me submit to when he shows me things as they are rather than as placeholders, the surprise that other persons can make me submit to when they show themselves as other than their place in the order—or me as other than my place in the order. In each case, however, even if I hold things lightly, I depend on something or someone other than myself to be surprised. I cannot surprise myself.

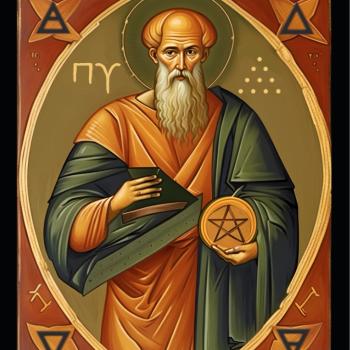

A religious name for allowing for newness and surprise is "openness to revelation." Howard Wettstein tells me that observant Jews have prayers for almost every act in the day, hundreds of possible prayers. Such prayers open the person to being surprised by the things and events over which he or she prays: prayer recognizes the independence of things; it refutes our will's claim to mastery and opens to the possibility of things being otherwise. My food is not mine. My home is not mine. Nothing is mine, whether entity, event, or order, so anything can surprise. Prayer recognizes that ultimately the possibility of surprise traces back to God.

Repentance and forgiveness are the ultimate possibility of things being otherwise, for in each I recognize that I am neither the center nor the creator of the world, that a knowledge of entities and events and orders as they really are must come from God. In them I let go of my desire to master the ordinary, to give it my order, and I am ordered anew by Another.

(This comes, as they say, with a hat-tip to Adam.)