This is a guest #longpost by Cathleen O’Grady. She is a South African writer, linguist, and freethinker with interests in education, social development, and the changing face of religious belief and skepticism.

***

In many countries around the world, religious groups are pushing for conservative social policies and retaining their grip on society by dominating the public discourse and provision of social services. In Uganda, an extraordinarily religious country, the small but vocal atheist movement is pushing back — hard.

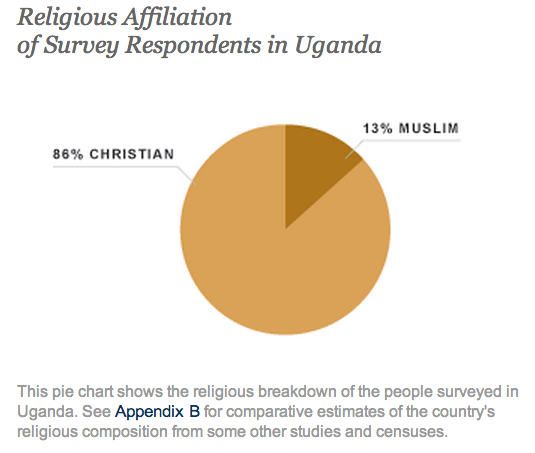

Although Ugandan law guarantees religious freedom, the reality is more complex. A 2010 Pew survey found that 99% of survey respondents in Uganda identified as religious, with 86% of them identifying as Christian and 13% as Muslim. That leaves 1% of the population to represent minority faiths (including Hinduism, African traditional belief systems, Baha’i, etc.) — and the non-religious. It’s worth noting that the religious population in Uganda is also, well, religious, with 86% of respondents indicating that religion is “very important” in their lives, 82% attending religious services weekly, and 71% of Christians and 74% of Muslims stating that their holy books are the literal word of God.

This is no mere Sunday Christianity: it infuses every aspect of people’s lives.

Despite the country’s secular laws, 64% of Christians and 66% of Muslims are in favor of making their religions the official law of the land. The president, Yoweri Museveni, is closely connected to the powerful Covenant Nations Church, headed by his daughter, and has been known to suggest that Ugandans are trusting God by placing their faith in him as president. His wife, Janet, is simultaneously a Member of Parliament and a patron of the Pentecostal churches of Uganda. She has also been reported to hint that her political power is God-given.

Even in a theoretically secular state, religion makes its presence known through the sheer majority of believers and the legislation they push. With 76% of the population believing that abortion is immoral, and 79% believing that homosexuality is morally wrong, it is no surprise that religiously-motivated legislation (such as the infamous Anti-Homosexuality Bill) garners popular support.

It is in this environment that the passionate atheist movement in Uganda has emerged, with few official organizations, but tangible effects and loud voices.

UHASSO, the Uganda Humanist Association, is an umbrella group uniting various Humanist organizations, with a strong focus on campaigning for social welfare, promoting unity across social boundaries, and promoting Humanism as a humane alternative to religious and ethnic fanaticism. The Atheist Association of Uganda was formed in 2009 to fight for the separation of church and state and challenge the harmful effects of superstition in Ugandan society. Freethought Kampala is an active society, holding monthly “Freethinkers’ Nights” providing a forum for discussion on a broad range of topics, including the Arab Spring, debating techniques, and the problem of skepticism running amok in the form of conspiracy theories. The society exists to promote freethought and critical thought, and attracts a wide audience to its events, stimulating dialogue in an audience of multiple faiths.

James “Fat Boy” Onen, radio DJ and co-founder of Freethought Kampala, didn’t feel the need to share his lack of religious belief until a discussion on his radio show about the upsurge in reported cases of ritual child sacrifice for the purposes of witchcraft:

“Public discourse was focused on how evil witchcraft was and how it was against God’s wishes, but no-one was talking about how irrational it was. Every attempt of mine to inject the rational perspective was met with resistance, because for a lot of people, witchcraft is viewed as the flip side to religion, and witchcraft is the handiwork of the Devil — so belief in the efficacy of witchcraft is tied to belief in the existence of God. To deny the efficacy of witchcraft was to deny Christianity and the existence of God and the Devil. When asked how I could not believe in the existence of witchcraft while still believing in a God, I kind of had to come clean and say, well, I don’t believe in God either.”

Belief in witchcraft and demonic possession is widespread in Uganda, with children sometimes accused of being possessed, as in the case of a primary school which was shut down following reports of the children being attacked by demons. African traditional religions predating Christianity are the root of the common belief in witchcraft, and James Onen suggests that the increasing popularity of Pentecostalism is responsible for providing support for this worldview:

“Charismatic Christianity is making things worse by over-emphasizing [superstition], by advertising it, by lending credence to the validity of claims that witchcraft is efficacious, by fully absorbing that worldview into their worldview.”

The effects of this belief on the people of Uganda are chilling: witchcraft-related practices have been reported to result in human sacrifice. Moreover, belief in the healing powers of witchcraft often results in people abandoning evidence-based medicine in favor of traditional healing, leading to devastating effects on the country’s battle against HIV/AIDS and related diseases such as tuberculosis.

James Onen resolved to make information about witchcraft, skepticism, and freethought in general available to the public:

“The idea was to set up a challenge to anybody to prove the efficacy of witchcraft, offering a cash reward of two million Ugandan shillings [US$750]. There was one serious challenger who came forward, but obviously it turned out to be a sham – we got there and the witchdoctor started telling stories and giving excuses about how he couldn’t do it on that day. My radio station is a mainstream commercial station, and a lot of people were interested to see the outcome. People rely on stories and hearsay to sustain their belief in witchcraft.”

There is an uneasy relationship between Pentecostal Christianity and witchcraft — while witchcraft is publicly reviled, many people seek medical or other help from witchdoctors when they are desperate. Onen says the beliefs are similar in many ways:

“The rituals and antics at the churches are almost identical to what you might see taking place in a shrine of a witchdoctor, like the casting out of spirits: it’s the same thing with a different name. A lot of people who flock to these churches are desperate; they need jobs, they need healing from chronic illnesses, and they have nowhere else to turn, so if healing at church doesn’t help, then they go to the witchdoctor. Human beings like to compartmentalize.”

Onen notes that Uganda’s poverty “might partly explain why religiosity and other forms of superstition persist, even when science has come a long way in providing explanations for a lot of things people attribute to the supernatural, such as sickness and poverty.” He suggests that freethought can only genuinely flourish in societies that are already doing well, because of the impossibility of convincing impoverished and illiterate people with no clinic for 100 miles to abandon their belief in witchdoctors.

“Uganda is a poor country, and social and medical services often aren’t available, so traditional healers are the go-to people. They provide herbal remedies, and at the same time some promote the notion that they have mystical powers as well. You have herbalists, guys who only do witchcraft, and those who dabble in both, but the line is very blurry in the minds of a lot of people, so the efficacy of herbal remedies sometimes reinforces the view that they have mystical powers.”

Because belief in witchcraft is closely tied to poverty and a lack of education, the work being done by humanist organizations to promote social welfare, health education, and freethought, is vital in the battle against the damage of superstitious beliefs.

Research shows a strong correlation between poverty and religiosity, albeit with notable exceptions, including the US, which has a higher rate of religiosity than its wealth would predict. Why is that? Common knowledge and research suggest that religion provides an important source of hope and comfort for those in desperate situations, a situation that unfortunately applies to many in Uganda. The country receives a very low rating of 2.4 out of a possible 10 on Transparency International’s scale of corruption perceptions, and has the highest estimated levels of corruption in the region. The effect of the widescale corruption is a shortage of jobs, as nepotism ensures employment opportunities only for a select few, and a gross shortage of service delivery. International donor funds are thought to be absorbed by the government with no tangible impact on the country’s citizens, causing a halt in foreign aid, a situation exacerbated by the anti-homosexuality bill in the pipelines. Child labor is common, and an estimated 38% of the population lives on $1.25 a day or less, with women badly affected by the country’s social problems.

This dire situation makes Onen’s question of how to reach the poorest of the poor a vital one for Uganda’s atheist movements, and the strong humanitarian work of Ugandan humanist organizations is providing a potential solution to the problem. By providing relief for the poor, working on social development projects, fighting government corruption, and advocating for a tolerant and peaceful society, humanist societies are sending a strong message that not only is religion not needed for morality, but also that a non-religious society can be as caring and strong as a religious one. UHASSO commits to promoting social welfare by establishing secular schools, health centers providing treatment for the poor and emphasizing health education, and humanist social centers promoting cohesion across social barriers. The Humanist Association for Leadership, Equity and Accountability (HALEA), an offshoot of UHASSO, works to protect vulnerable, marginalized, and minority groups in Kagugube, a slum area of Kampala.

Perhaps most remarkable about Ugandan humanist movements is the founding of explicitly humanist schools. The Uganda Humanist Schools Trust raises funds to support three humanist schools: The Isaac Newton High School, Mustard Seed School, and the Humanist Academy. The schools serve impoverished rural communities, providing an otherwise-unattainable secondary education for children growing up without electricity, sanitation, or running water, many of whom are orphans. While the Humanist Academy unfortunately closed its doors in 2010 due to a lack of funding, Isaac Newton High School and the Mustard Seed School are producing students of a high calibre, with many school-leavers achieving excellent grades and receiving places and funding at Makerere University, an extraordinary achievement for pupils from a rural school in Uganda. These schools are still small, with 195 pupils at Isaac Newton High School in 2012, and 257 at the Mustard Seed School. It’s a drop in the ocean when considering the estimated 195,860 students at government-run secondary schools and further 105,840 at private schools, as well as the estimated 113,455 students unable to gain entry to secondary education in 2012. But with large class sizes and constant financial struggles, the humanist schools need to be able to pay more teachers in order to expand.

Kasese Humanist Primary School, run by the Kasese United Humanist Association, offers primary education and nursery services to a number of children in the western Ugandan Kasese District. All these schools have a strong emphasis on freedom of thought and rational inquiry, as well as human rights and social equality. In a country in which a great deal of education is provided by religious organizations, these schools play a vital role in providing a secular education and in alleviating the dire poverty through feeding schemes and vocational training

Robert Bwambale, the founder of Kasese Humanist Primary School, is a passionate advocate for the role of Humanism in social upliftment.

“[I started the school] to bring humanism and atheism to the attention of Ugandans, to generate a breed of like-minded individuals who can think for themselves, make decisions, and embrace reason. I was not happy seeing almost all the schools in Uganda with an attachment to a religious sect, and I thought that our children should instead study religion on comparative terms and encourage science and critical thinking instead.”

Having challenged and lost his Christian faith while studying Biology in college, Bwambale is determined to make information about science available to others. In addition to the primary school, he opened a public library with lots of literature on freethought and science:

“I initiated Kasese United Humanist Association in 2009 because I thought it could assist me in advancing freethought and secular views to the people. I went public because I was determined to put in place a fundamental change in informing people about positive living, critical thinking, and free inquiry into the most pressing questions about life, religions, gods, and the role of humanity in this ecosystem of vast biodiversity.”

The school has had some success with its mission, although it constantly faces the challenge of changing minds in the local community:

“Informing the locals that the school is built on a scientific foundation, embracing humanist values and ethics, has symbolized to the locals that we are harmless people, kind, non-discriminatory, compassionate, and honest, advocating for reason and evidence. Many people who visit the school compliment us about the work we are doing, while those with mixed feelings about our non-belief in a god sometimes pose some questions, which we give answers to. The school presence has opened a path that can be used to promote freethought philosophy among the Ugandan people.”

Bwambale feels that one of the greatest challenges facing atheism in Uganda is the lack of unity among atheist organizations.

“Atheist groups exist in small groups, and some people fear to identify themselves as atheists as they fear isolation, discrimination or excommunication from their clans or tribes… I had an interest in uniting humanity so that we look at ourselves as one. I also wanted to mobilize and unite like-minded individuals with rational ideas and views to come up as a single unit and initiate viable projects in the name of freethought that can help foster economic, social and political development among the Ugandan people.”

Onen feels that Freethought Kampala and Humanist organizations like Kasese are tackling different sides of the same problem. While Humanist groups operate at a community level, raising funds to provide services, Freethought Kampala provides a place for educated, sophisticated city-dwellers to have a conversation.

“Our goal is to inject the rational perspective into issues on public discourse, and we use social media, the Internet, and also mainstream media. The people we are trying to talk to are the people from a similar social and economic background to us — these people have degrees, they’re educated, but many still have irrational beliefs, so our approach is to interact with those people and hope that there might be a trickle-down effect: that next time someone thinks about getting healing from the church, he might think, ‘Oh, I’ve heard these guys aren’t legit, I might want to see a doctor instead.’”

The strength and vigor of the small Ugandan freethought movement is remarkable, and the various humanist organizations’ work to improve social welfare and human rights is providing a tangible solution to the problem of how to address religious extremism in poor societies. Although the non-religious population in Uganda is tiny, the fact that so much work needs to be done in order to boost Ugandan society and ensure that human rights are widely upheld surely adds fuel to the fire of those Ugandan atheists who are brave enough to lend their voices publicly to the cause. One Ugandan activist, Micheal Mpagi Kirumira, is calling for outreach from the first world, suggesting that speakers and activists from the U.S. assist in countering the evangelism of American Christians. Bwambale says that because Ugandan atheist groups have little support locally, and little support from well-established charities worldwide, their only chance of attaining substantial funding is the support they receive from secular charities, such as Foundation Beyond Belief. With the International Humanist and Ethical Union having been involved in two humanist conferences in Kampala, in 2004 and 2009, it is to be hoped that this vibrant atheist movement is drawn further into the international atheist community, and that it receives the support it deserves.

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."