The best-known conversion story has got to be St. Paul's. In the time it took the scales to fall from his eyes, he went from ice-cold on Christianity to red-hot. And that's exactly how he stayed—even if, at times, he found himself doing things he hated—until his beheading. Second place might go to St. Augustine; third, perhaps, to Cardinal Newman, but since I don't know much about him, I'll give his spot to Thomas Merton. Neither had the honor of dying for the faith, but no less than St. Paul, they apologized for it tirelessly, and put as much daylight between their pre- and post-conversion selves as possible.

The best-known conversion story has got to be St. Paul's. In the time it took the scales to fall from his eyes, he went from ice-cold on Christianity to red-hot. And that's exactly how he stayed—even if, at times, he found himself doing things he hated—until his beheading. Second place might go to St. Augustine; third, perhaps, to Cardinal Newman, but since I don't know much about him, I'll give his spot to Thomas Merton. Neither had the honor of dying for the faith, but no less than St. Paul, they apologized for it tirelessly, and put as much daylight between their pre- and post-conversion selves as possible.

It's understandable that these are the sorts of stories that Catholics love to read; they support the idea that conversion entails exactly the kind of change of mind that Greek-speakers promised when they named it metanoia. It makes sense that they would dominate the marketplace. Who would want to write of an incomplete conversion, or one begun from questionable motives? Stories about conversion from Catholicism to something else are a dime a dozen, Anne Rice's being only the most recent. But those, too, represent a kind of completeness. If St. Paul was on fire, Anne Rice is frozen over. What about those who are lukewarm?

I wish more of these stories were in circulation. Most of the Church's think tank, from theology departments to Bishops' Conference subcommittees, is made up of people who are inclined to commit to an idea or some version of that idea for the idea's own sake. In Chaim Potok's The Promise, a rabbi remarks wistfully that the students he'd taught in Europe spoke of Torah as though they were reciting the Song of Songs. He is baffled to note that American seminarians seem to lack that passion. In this, I think, he is typical; ideologues and non-ideologues occupy such drastically different headspaces that they have scant hope of communicating without frustrating each other.

It may be time they learned. A recent Pew Research Center study shows that people leave the Church for largely non-ideological reasons. In analyzing the data, Fr. Thomas Reese says that "about half" of the defectors left because the Church "failed to meet their spiritual needs." Peter Steinfels remarks that the other slightly-more-than-half "reported having had a weaker faith in their childhood and significantly lower Mass attendance as teens." Big metaphysical ideas seem never to have made it onto their radar to begin with.

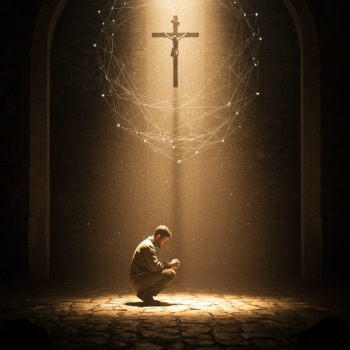

I seek to fit these trends into the question of adult conversion because I'm an adult convert myself. And I'm no St. Paul. I joined the Church because I felt a vague but pervasive dissatisfaction with my life as I knew it. What keeps me around is a vague but pervasive sense of vocation. It operates independently of any intellectual conviction concerning the rightness of Church teachings, or even of God's existence. I'm here, in short, because I'm here.

Judging by my own experiences in my parish's RCIA program, this isn't uncommon; indeed, it may even be the norm. Of all the converts I got to know during my time as a candidate, and later, during my time as a sponsor, only a few seemed to be in it because Catholicism explained the world to them more coherently and agreeably than any other thought system. The rest were acting from some other motive: plans to marry a Catholic, a promise to a dying parent, a random burst of enthusiasm. This isn't to say that our conversions were cynical; I can state without reservation that every single one of us wanted, at least for the duration of the course, to be a good Catholic. It remains to be seen whether our motives will sustain us over the long haul.

Many observers these days complain about poor catechesis. Honestly, I'm not sure how to rate mine, since I have nothing to compare it to, not even an ideal. Considering the relevant material had over 3,000 years to accumulate, it felt pretty thorough. What the course made no attempt to do was weed out non-hackers—people whose commitment seemed likely to falter for one reason or another. This seemed calculated; no one ever said as much, but I gathered it was thought best to claim as many souls as possible up front, leaving maintenance issues to arise when they would.