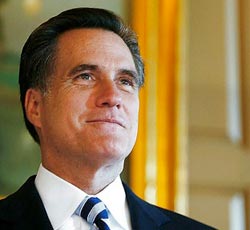

When America moved into the most recent incarnation of the Mormon Moment, some observers—including myself—assumed that this implied moving beyond the question of whether Mormons are Christian. But old habits die hard. This week, "Fox & Friends" co-host Ainsley Earhardt made headlines by declaring that presidential candidate and Mormon believer Mitt Romney was not a Christian. When explaining why Texas Governor Rick Perry had an advantage over Romney in raising money, Earhardt explained how Perry "can get a lot of money from [the Christian coalition] because [of] Romney obviously not being Christian."

When America moved into the most recent incarnation of the Mormon Moment, some observers—including myself—assumed that this implied moving beyond the question of whether Mormons are Christian. But old habits die hard. This week, "Fox & Friends" co-host Ainsley Earhardt made headlines by declaring that presidential candidate and Mormon believer Mitt Romney was not a Christian. When explaining why Texas Governor Rick Perry had an advantage over Romney in raising money, Earhardt explained how Perry "can get a lot of money from [the Christian coalition] because [of] Romney obviously not being Christian."

This is an old issue for Romney. During his run in the last presidential campaign, he was compelled to deliver a high-profile "Faith in America" speech. "I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and the Savior of mankind," he said. And the issue is even older for Mormonism in general. As former Latter-Day Saints President Gordon B. Hinckley emphasized, "We are Christians in a very real sense.... We, of course, accept Jesus Christ as our Leader, our King, our Savior." Detractors claim that the "Christ" Mormons worship is radically different, and thus deserving of a different descriptor. Mormons claim that the only standard for the "Christian" title is sincere belief in the Savior. And so the debate goes around in circles.

Mike Huckabee made hay with the issue in the 2008 presidential race, and with Romney and Jon Huntsman campaigning now, we can expect to be hearing more of this age-old conflict.

But this debate—Are Mormons Christians, or aren't they?—is asking the wrong question. Being a Christian is clearly important to a majority of American citizens, but the debate over who is and who isn't "Christian" ignores vast divergences within the Christian tradition. The label "Christian" means very little in American discourse because it assumes too much and explains too little. Earhardt-style rhetoric and the debates that ensue are a red herring, distracting us from deeper issues.

Though America has long claimed to be a "Christian" nation, what "Christian" means has varied widely. "American depictions of [Jesus]," Stephen Prothero detailed in his American Jesus: How the Son of God Became a National Icon, "have varied widely from age to age and community to community." The early American republic has been described as a "spiritual hothouse" where competing religions battled over who had the legitimate claim to pure Christianity. From literary figure Thomas Branagan's Concise View of the Principal Religious Denominations in the United States of America (1811), which sought to determine the "true sentiments" of Christian groups, to clergyman Robert Baird's Religion in America (1842), which sought to differentiate legitimate traditions from heretical sects, the habit of excluding some Christianities while stabilizing others is an impulse as American as apple pie.

And again, Mormonism has long been caught up in these debates. Joseph Smith's prophetic claims were deemed not a result of religious interpretation, but as the ravings of a charlatan or impostor. In his book The Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myths, and the Construction of Heresy, Terryl Givens documents how Mormons where characterized as a heretical "other" as a way to hide national and religious disunity in nineteenth-century America. Mormonism became a tool, he explains, for fulfilling a "need to exaggerate disparity so that boundaries [could] be imposed and enforced." Describing the Mormon faith—or any religion, for that matter—as non-Christian meant dismissing them out of hand, without further consideration. The label of "Christian" was a badge of American authority, a vindication of recognized precepts, and was therefore used as a tool in dispelling threats. Then as now, in public discourse, orthodoxy was more of a bludgeon than a belief.

This rhetorical framing of Christianity has been so ingrained in American culture that it is now taken for granted. When something—or someone—is described as "Christian," it is implied that there is a clear, definitive list of what constitutes that label. But such clarity couldn't be further from the truth. The appellation has always been, and perhaps always will be, an agenda-driven strategy in excluding purported deviants.

When Evangelicals describe Mormonism as "non-Christian," they generally mean that Mormons don't adhere to early Christian creeds. When Mormons claim the title of "Christian," they generally mean they worship Christ as the Son of God. In reality, rather than being on opposite poles of a distinct debate, Mormons and Evangelicals are merely two points along a long, dynamic, and diverse spectrum—not to mention the long, dynamic, and diverse spectrums within Mormonism and Evangelicalism themselves. But such nuances have no role in religious debates, let along political talk shows, and thus simplistic and misleading characterizations arise.

The label of Christian serves less as a devotional identifier and more as a polemical tool. It hides "safe" diversity while highlighting "devious" distinctions. It attempts to package religion in a clear, simplified, and categorical manner where "orthodoxy" and "heresy" are separated in a clear dichotomous fashion. It implies a commonsensical observation-- Ainsley Earhardt's "obviously..."—that settles debate even before any deeper engagement is accomplished.

But religion—and especially Christianity—has never been that simple.

7/21/2011 4:00:00 AM