Lectionary Reflections on Deuteronomy 26:1-11, for Thanksgiving

Lectionary Reflections on Deuteronomy 26:1-11, for Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving has become in our culture a nostalgic celebration of family, food, and football. Food is the center of the day, the groaning board made heavy with turkey (or the vegetarian equivalent thereof), stuffing of oyster or mushroom or (ugh) unmentionable parts of the bird, cranberries, mashed potatoes (my favorite), and succulent kinds of pie: pecan, mince, apple, and on and on. My mouth waters at the memories and the anticipation of a too-tight belt and a promised extra trip to the gym. Uncle Alvin and Aunt June come, he of the hearty laugh and the slightly off-color stories and she of the willingness to sit at the dreaded children’s table where 10 year olds are imprisoned with the terrible 5 year olds, and the drumstick is fought over like sacred land.

And speaking of sacred land, Deuteronomy has much to teach us about Thanksgiving. Chapter 26 provides a snapshot of worship that centers on the gift of food and the meanings of the gift and the several implications of the gift. There is nothing wrong with food offered, but there is plenty wrong with food hoarded and hidden and consumed with no thought about why or where or who.

The chapter ties together three very important facets of Israelite belief and practice: history and worship and invitation. The very origins of the people of Israel are rooted in the gift of land. Over and again the ancient forebears of Israel are promised the land as a sign of God’s ongoing presence. “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you,” announces God to Abram and Sarai (Gen. 12:1), the couple destined to found the nation and the land. This sacred land is “an inheritance,” a gift from God to Abram and his family and all subsequent generations who claim kinship with them. This patriarchal and matriarchal promise/blessing is passed down through all the descendants in a cascading shower of gift and memory. The history of the gift grounds the life of Israel in the very soil on which they live and from which they prosper.

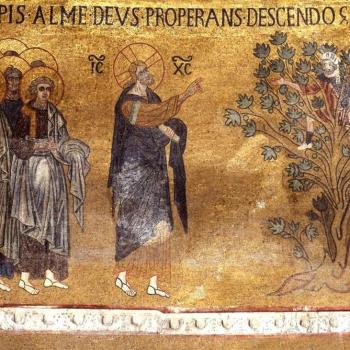

Of course, their first worshipping act, then, should be a gift back to God from this same soil; “you shall take some of the first of all the fruit of the ground, which you harvest from the land that YHWH your God is giving you.” There appears to be a distant memory here of an infamous struggle over proper offerings in the book of Genesis. In chapter 4:3, we are told that “Cain brought some of the fruit of the ground” for an offering to YHWH. In 4:4, “Abel brought, even he, the very best from his flock, that is their fattest, oiliest portions.” I translate quite literally to suggest that Abel’s offering was of the best, while Cain’s offering appears grudging, merely “some,” perhaps a moldy rutabaga he had lying about. The result is that “God had no regard for Cain’s offering” (4:5). Rabbis and later historical scholars have long argued about the meaning of these enigmatic words, but Deuteronomy has no doubt that the gift of the fruit of the ground should be only the “first,” that is both the earliest production of the ground and the best. We in the modern world would say, “off the top.”

Once the best fruit has been selected as the proper gift to God, the worshipper is to put it in a basket, bring it to the priest who is in authority, and say, “Today I declare to YHWH your God that I have come into the land that YHWH swore to give to our ancestors” (vs. 3). The priest is then to take the basket and set it down before the altar. And then the supplicant is to respond as follows: “A wandering Aramean was my ancestor.”

There is a wonderful dual meaning in the word “wandering.” That word may also mean “perishing.” I have the strong suspicion that both meanings are intended. Israel in its ancient memory often described itself as wandering, rootless, landless. And because that is so, they were also “perishing,” threatened, fearful, victims of nations and peoples far more powerful than they. The recital continues: “he went down into Egypt and lived there as an alien (immigrant), few in number, and there he became a great nation, mighty and populous.” Israel’s long sojourn among the Egyptians, a central core of their story, ended with their enormous growth in numbers and power (Ex. 1:7). This made the Egyptians and the pharaoh afraid, so “they treated us harshly and afflicted us by imposing hard labor upon us” (Ex. 1:11-14). So, they cried to YHWH, who “heard our voice and saw our affliction, our toil, and our oppression” (Ex. 2:23-25). “YHWH brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, with a terrifying display of power, and with signs and wonders” (Ex. 3-15).