Not long ago I had a telling conversation with a woman who was well-to-do and intelligent. The subject was healthcare and she asserted that her children (who were all adults) should have any medical attention that they needed, free of expense.

Not long ago I had a telling conversation with a woman who was well-to-do and intelligent. The subject was healthcare and she asserted that her children (who were all adults) should have any medical attention that they needed, free of expense.

I said that I could understand her desire, but that medical care was, in fact, quite expensive—whether, in fact, it was always rightly as expensive as it is. I pointed out, for example, that before an MD even begins practicing medicine, the average physician incurs $750,000 to $1,250,000 in debt getting a medical education and setting up a practice.

"I don't care," she said. "I don't think that anyone should make money doing it."

Her refusal to think at all about the realities of healthcare was jarring. What the conversation taught me is that bright, otherwise reasonable people are unwilling to think deeply about some, if not a lot, of the issues that are part and parcel of life's challenges.

That tendency manifests itself in a number of ways:

- Some of us simply assert that we want what we want, the details be damned.

- Some invent unseen or unknown culprits to account for the fact that we can't have what we want or that things are not as good as they should be.

- Others generate conspiracy theories or demonize others.

- Still others simply believe that others—government, for example, should resolve the problems—and that, if the problems persist, the same "others" are responsible for the failure to resolve them.

- And some reject the discipline of thinking about the issues at all, embracing a primitivism that argues the complexities are really the product of too much thinking, hearkening back to the "good old days" or lionizing other ways of life that are ostensibly simpler in their approach.

All five approaches are on display in every arena of life.

You see them in politics where demonization is rife both on the left and the right. That's long been common among an electorate that has no taste for a conversation about the complexity of modern life (which is why we are surrounded by politicians with simple answers to complex problems).

You can hear it in the happy-clappy speeches that leaders of all kinds give who say what needs to be said to get from here to the next job or retirement (like the politician who argues that the crisis in Medicare is not that big a deal; the church leader who says his church isn't dying, "it's just embracing a new, smaller mission"; or the seminary president who argues, "we've sold our property, we don't give degrees, but that's because we are on the cutting edge of theological education").

You can see it in the church, where the preparation of clergy has been dumbed-down, appealing to bureaucratic exigency, historically bogus distinctions between missional and Constantinian churches, and the argument that theological sophistication is a pointless (if not dangerous) indulgence.

To a degree, the tendency to run from thinking hard is understandable. It is hard to engage all of life's issues, all of the time, at the same depth. And most of us feel disenfranchised to one degree or another in ways that rob us of the motive to participate. But the retreat into demonizing one another or into a primitivism that over simplifies the challenges we face makes it very difficult to get at the truth of a situation, never mind workable solutions.

But is thinking hard a spiritual issue? Yes.

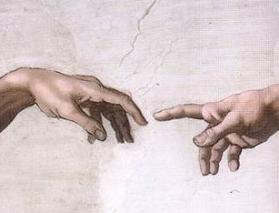

Genesis describes humankind as having been given responsibility for the world in which we live. Like it or not, that responsibility may be the first and God-given task that we all share. So, thinking hard about the challenges we face is a God-given obligation. And the flight into our own chosen refuge from the demands of modern life is not just a matter of laziness, it is a matter of spiritual dereliction.

According to Jewish folk wisdom, two men were fighting over a tract of land, each claiming ownership. In order to resolve the dispute they made their respective case to their rabbi, who listened, but was unable to discern the right decision. Finally he said, "Since I cannot decide to whom this land belongs, let us ask the land." He put his ear to the ground, then straightened up. "My friends, the land says that it belongs to neither of you—but that you belong to it."

Our growth and our spiritual destiny do not lie in either bending the world to our appetites, or in running from its challenges. They will be found in thoughtful living that requires the spiritual discipline to think hard.

1/17/2011 5:00:00 AM