Early 19th-century America was an exciting time, an age of reform. Known as "the era of the common man," it saw a movement toward greater democratization. It witnessed the rise of Transcendentalism, the creation of utopian communities like Oneida and Brook Farm, the birth of the feminist movement, and the growth of abolitionism. In the area of religion, it was an era of intensive questioning and spiritual searching.

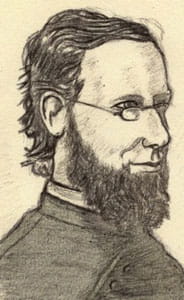

One of those seekers was a young New Yorker named Isaac Hecker (1819-1888), whose spiritual journey led him from politics to Transcendentalism and Brook Farm, and ultimately to the Catholic Church. It led to friendships with Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. It led him to conclude that Catholicism alone fully met the day's needs, spiritual and social, and as a priest he dedicated his life to the conversion of America.

One of those seekers was a young New Yorker named Isaac Hecker (1819-1888), whose spiritual journey led him from politics to Transcendentalism and Brook Farm, and ultimately to the Catholic Church. It led to friendships with Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. It led him to conclude that Catholicism alone fully met the day's needs, spiritual and social, and as a priest he dedicated his life to the conversion of America.

Born in Manhattan to a German-American family, Isaac Thomas Hecker was baptized Lutheran. His formal schooling was minimal, and he worked in the family bakery (Hecker Flour is still found on supermarket shelves). His early work in political organizing disillusioned him, and contact with reformer Orestes Brownson convinced him that true reform, social and political, needed a religious underpinning.

This was the beginning of his spiritual journey. In early 1842 he had what he described as a "vision" that left him "unconscious of anything but pure love and joy." It was a turning point in his life. At Brook Farm he mingled freely with some of the day's leading intellectuals, but he was spiritually unsatisfied, and he turned to traditional Christianity for answers.

Through reading, travel, and conversation, Hecker concluded that Catholicism alone embraced "the full range of the Christian experience." It offered a unity Protestantism lacked, and it balanced personal piety with social activism. In August 1844, he was baptized a Catholic. His conversion surprised friends. When Emerson asked Hecker if art and architecture had "turned his head," he replied, "No, but what caused all that."

Hecker had also decided to become a priest. In August 1845, he joined the Redemptorists, an order he admired for its pastoral bent. (The Jesuits he considered too academic.) He was ordained in October 1849. In a letter home, he wrote: "All my seeking is now ended . . . I have found all that I have ever sought."

Father Hecker was assigned to a team of priests who traveled the country preaching parish missions. These were week-long events promoting repentance and renewal, composed of morning and evening lectures followed by confession. While these were primarily Catholic affairs, Hecker and his fellow missioners, all converts, wanted to extend their work to non-Catholics, as Hecker said, "to convert a certain class of persons among whom I found myself before my conversion."

In 1858, Hecker and four confreres left the Redemptorists to form the Missionary Society of St. Paul the Apostle, known as the Paulists. All converts, they were an impressive group: George Deshon was a West Pointer and friend of Ulysses S. Grant; Clarence Walworth was considered the nation's finest Catholic preacher; Augustine Hewit, the grandson of a senator, was an accomplished writer; Francis Asbury Baker had been a prominent minister in Baltimore. Together they would evangelize America. Hecker wrote: "I feel like . . . adopting one word as our motto -- CONQUER!"

During the 1850s, anti-Catholicism was widespread and powerful, and many Catholics took the defensive. Hecker aimed not merely to refute prejudice, but to persuade Protestants that they should convert. Instead of proceeding from doctrinal premises, Paulist preachers emphasized shared human experiences and the search for truth, arguing that Catholicism best met the needs of the soul and of society. Hecker wanted to convert Americans not for the Church's sake, but for theirs.

He had no place for condemnation. In 1868, a minister described him as "a happy man -- happy in his faith and in his work."A friend called him "one of those men whom you feel it is good to be with." But he also felt an urgency (and impatience) about his work. One Paulist described his "contempt for lazy devotion":

Once, when upon a mission, a young priest just returned from Rome, where he had made his studies, expressed his desire to get back again to Italy as soon as possible, saying, "I find no time here to pray." Father Hecker felt indignant, for it did not seem to him that the young man was very much occupied. "Don't be such a baby," said he. "Look around and see how much work there is to be done here. Is it not better to make some return to God -- here in your own country -- for what He has done for you, rather than to be sucking your thumbs abroad! What kind of piety do you call that?"