By J. Ryan Parker

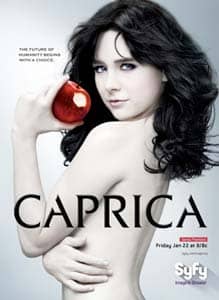

Nearly every episode of the five seasons of Battlestar Galacticaoffered fodder for theological, moral, or ethical discussion, while also providing an action-packed, engaging narrative. Building on the success of this series, the creators developed a prequel series, Caprica, which takes place on the titular planet and focuses on the Adama and Graystone families, both of whom suffer a devastating tragedy in the first episode.

Nearly every episode of the five seasons of Battlestar Galacticaoffered fodder for theological, moral, or ethical discussion, while also providing an action-packed, engaging narrative. Building on the success of this series, the creators developed a prequel series, Caprica, which takes place on the titular planet and focuses on the Adama and Graystone families, both of whom suffer a devastating tragedy in the first episode.

Caprica is vastly different than its inter-stellar predecessors. Yet if viewers abandon any preconceived hopes based on Battlestar, they will be rewarded by this new series. First and foremost, Caprica establishes the monotheistic vs. polytheistic tension that was so integral to Battlestar. In the first episode, a Soldiers of the One (S.T.O., the underground monotheist group) terrorist bombing rocks Caprica as one of its members blows up a commuter train, claiming the life of Joseph Adama's wife and daughter, Tamara, and Daniel and Amanda Graystone's daughter Zoe, along with dozens of other citizens. Yet thanks to Graystone Industry's virtual technology in the form of the Holoban (virtual reality glasses that allow for both game-play and social interaction), both of the girls live on through their avatars (virtual selves). Zoe, unbeknownst to her family, is a critical component to the S.T.O's agenda given both her technical know-how and her dreams for the V-World (she hopes to extend real life through virtual life). In fact, Clarice, a religious leader in the S.T.O., views Zoe's avatar as an extension of her soul into eternity. With the help of her friends, Zoe manages to have her avatar downloaded into one of her father's robots, a precursor of Battlestar's Cylons. As the season progresses, Zoe attempts to get the robot, and her avatar, off Caprica and to Gemenon (apparently a more religiously diverse planet), which is where she and her friends were attempting to go when the train exploded (one of her colleagues was the bomber).

While there are many talking points to this series (faith, fundamentalism, grief, loss, etc.), what I find especially interesting is the relationship between the real and virtual worlds in Caprica. I find this especially interesting given our entry into Holy Week and our upcoming reflection on and celebration of Jesus' death and resurrection. In the virtual world of Caprica, two dead girls live on. The immediate debate, of course, is over whether or not their virtual selves are real, or as real as, their former real world selves. Frankly, this is not a debate that I necessarily want to entertain here, because, as in the series, I want to affirm the reality of their, and by extension our, virtual selves.

While there are many talking points to this series (faith, fundamentalism, grief, loss, etc.), what I find especially interesting is the relationship between the real and virtual worlds in Caprica. I find this especially interesting given our entry into Holy Week and our upcoming reflection on and celebration of Jesus' death and resurrection. In the virtual world of Caprica, two dead girls live on. The immediate debate, of course, is over whether or not their virtual selves are real, or as real as, their former real world selves. Frankly, this is not a debate that I necessarily want to entertain here, because, as in the series, I want to affirm the reality of their, and by extension our, virtual selves.

In Caprica, virtual Zoe Graystone and Tamara Adama have extensive effects on people and events in the real world. They both reach out to virtual and real family members and friends for help and consolation. Zoe uses both the virtual and real Lacy and Philomon (it shouldn't take you too long to figure out the Biblical parallels to this one!) to aid her escape from Daniel's lab and her departure to Gemanon. Tamara pleads with a virtual New Cap City participant to find her father in the real world to visit her in the virtual one and help explain what is happening to her. Again, these virtual selves have an impact on people still living in the real world, and, thankfully, Caprica shows that these effects are not all positive. In his quest to find his daughter, and his inability to fully let go of her, Joseph Adama becomes addicted to both the Holoban and the virtual "amp" drugs that heighten his performance within the V-World. In the process, he begins to neglect his son, the young William Adama, who will later become Battlestar's Admiral Adama, which explains the son's disdain for his father in that series.

Lest you feel that the tension between the virtual and real worlds of Caprica is some sci-fi flight of fancy, consider the virtual worlds that you most likely daily inhabit. You probably have a Twitter account, a Facebook page, a MySpace account (that you've most likely abandoned), a blog, a website, a Linked-In account, a PlayStation or X-Box 360 account, a Wii Mii, and the list goes on and on. Theology and popular culture scholar Craig Detweiler writes, "Before my children reached second grade, they already had a second life and multiple projected selves" (Halos and Avatars, 2). What happens to these virtual selves when our real selves no longer exist? In talking about Caprica and this topic with my wife, she recalled a recent Facebook experience in which the social networking site suggested that she reconnect with a friend that she hadn't interacted with in quite some time. The problem? That friend had been dead for almost three years. While this is not a unique experience to my wife, it does highlight the fact that her friend's virtual self out-lived her real self. Facebook employees have even faced this tension and blogged about it, suggesting "memorialized" Facebook profiles.