By Rabbi Maurice Lamm

God expects every Jew to be a full-time Jew, not a Jew for Sabbaths only. God created the Sabbath and made it holy. But He also created weekdays. On weekdays, man must make himself holy -- in his morals and his thinking and his study and in his empathy and support of others. Tuesday is also Jewish. If a person is a believer on the Sabbath, he should be one every day.

God expects every Jew to be a full-time Jew, not a Jew for Sabbaths only. God created the Sabbath and made it holy. But He also created weekdays. On weekdays, man must make himself holy -- in his morals and his thinking and his study and in his empathy and support of others. Tuesday is also Jewish. If a person is a believer on the Sabbath, he should be one every day.

The reverse is also true. Jews do not believe in a Sabbath God, or a Holy-Day God, or a Rites-of-Passage God. God is a part of life. He is all of life. He is everywhere or He is nowhere. His majesty cannot be contained within a synagogue ark, or squeezed into the stone walls of Jerusalem, or locked tight in the 25-hours of Yom Kippur.

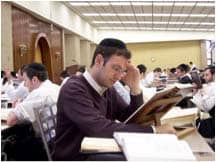

Torah study is every day, as surely as are food and thought and worry. Ethics are everywhere, in the kindergarten, the corporate office, and the bedroom. The sacred in Judaism is not limited to the Inner Sanctum; it has battles to wage in the streets.

Now, people are not naturally mindful of the supernatural. Therefore, the Torah makes every effort at jogging the consciousness of human beings, and it positions religious symbols as flashing beacons on all the pathways of life. After a while -- subtly, subliminally, suddenly -- the sense of God grows inside us and is everywhere. It is joy and meaning and hope and love.

There are special signals at the pivotal turns in life, at the major passages of our personal histories, and also at smaller cycles, when the wheel of time cranks its staccato rotations the turn of the week, the month, the season, the year. God is everywhere, all the time, urging us to make ourselves holy.

Among the constants of Jewish religious life, acts of kindness dominate.

The Meaning of Chesed

What is quite clearly the most consistent and all-embracing act of faith is called chesed, which means kindness and implies the giving of oneself to helping another without regard to compensation.

In a sense, the goal of the whole enterprise of Judaism is to develop human beings whose principal trait is chesed. The rabbis of the Talmud (Yevamot 79a) considered kindness to be one of the three distinguishing marks of the Jew.

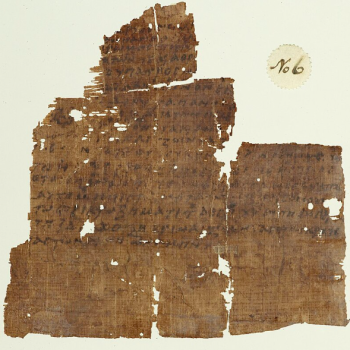

A favorite Talmudic name for God is Rachmana, "the Compassionate One." Every act of human chesed is an imitation of the benevolence of God. It appears on page after page of the Jewish Prayerbook, in chapter after chapter of the Psalms, and is implied in the legal and moral decisions on folio after folio of the Talmud.

The Torah begins with an act of chesed as God clothes Adam and Eve, and ends with it as God buries Moses. Jewish Law formally begins with the Torah at Mt. Sinai, but chesed begins with Abraham, centuries earlier. The world could not have endured so long without chesed; it would have imploded.

Chesed is a daily requirement, which means it is a lifetime requirement, and it is most succinctly manifested in the act of giving. It implies attitudes integral to the person's character, inseparable from one's inner nature, and spans the whole gamut of virtues, which operate in interpersonal relationships -- charity and compassion, love and respect.

This inner sensitivity is expressed in specific formal religious acts, which are commandments that have biblical or rabbinic warrant. These mitzvot are not merely "nice," suggested behaviors, but duties mandated the Jew.

Maimonides catalogues the commandments, which are the chesed principles in action:

It is a positive mitzvah of the Rabbis to visit the sick, to bring comfort to the mourners, to help remove the dead from the home, to help bring the bride to her wedding, to accompany guests into your house, to participate in all aspects of burial -- to carry the casket, walk in honor before it, eulogize the dead, dig the grave, and do the actual burial -- to bring joy to a bride and groom and to provide them with all their needs. These are all physical acts of kindness and there are no limits to what one must do to fill these requirements.

This inventory of virtues is only a short list derived from these specific verses. A longer list, the elements of which appear throughout the millennial Jewish literature, includes granting interest-free loans to the needy, feeding the hungry anonymously, giving shelter to the homeless, providing jobs for those in need of work, speaking kindly to the dejected, bringing enemies together in friendship, imparting hope to the depressed, giving extra care to widows and orphans, and so on.