Get Low

Get Low

Get Low, like Big Fish (2003), focuses on the importance of telling our story and the occasional necessity of helping others tell theirs. The rumors and lies about Felix (Robert Duvall), along with his friends' genuine concern for him, ask us whether we can ever really know anyone or not. Felix has kept his story bottled up inside him for over forty years; he has imprisoned it, much like he has imprisoned himself. As such, Felix's first funeral is a transformation from a burdened life into a liberated one that results from the act of telling his story. The film also calls into question our relationship to time and how we live our lives in the face of tragedy and loss. This first funeral for his story allows Felix to basically begin living his life again, to move forward, and to eventually meet his second, and final, death.

The Kids Are All Right

The Kids Are All Right

Richard and I were talking about reviews of mainstream films that feature gay and lesbian couples in lead roles and how reviewers often argue that these films aren't about homosexuality or homosexuals but rather about human beings. These reviews clearly hope to allay potential viewers' fears about these films being "too gay." In the process, however, their emphasis on the humanness of their gay or lesbian characters becomes somewhat condescending. So we'll say this straight away, The Kids Are All Right is about lesbians. There, we said it. Nic (Annette Bening) and Jules' (Julianne Moore) marriage is at the center of this film along with all of the ups, downs, and difficulties they face, some of which may be familiar to everyone who has ever been in a long-term relationship and many of which won't. Toward the end of the film, Nic's impassioned description of what it means to be in a committed relationship with another person cuts to the heart of the matter and transcends all the idealistic portrayals of it in which so many films, be they secular or Christian, traffic. The Kids Are All Right is one of those few films that show that marriage might be all about love and good times, but it's just as often about slogging through the shit.

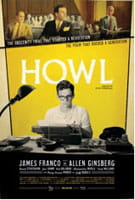

Howl

Howl

What got to me (Richard) about the film and still gets to me about the poem is its daring combination of the erotic and the spiritual. The secret to the continued relevance of Allen Ginsberg's prophecy is naked honesty. In the film, Ginsberg explains that when we're talking to friends, especially close ones, we don't edit our conversation. We go on about politics, drugs, neuroses, sex—whatever crosses our minds—but for some reason we aren't this free in our relationship with the Divine. We fail to see that if there is a being so intimate to life as to construct our bodies from the dust of the earth and give us breath and spirit, that being clearly knows we think about sex and use the toilet. What—in God's name—are we doing as religious people if we can't bring our whole selves before God as an act of faith? For Christians, if the idea of incarnation means anything, it's that God gets us . . . and loves us. There is nothing we can or need to hide.

Tron

Tron

Tron: Legacy is one of the best trips you'll ever take without drugs. The best casting in this film was the music of Daft Punk. The music positions the film as what it truly is: a techno-rave and special effects extravaganza. But something about Tron the original, and Tron the sequel on cyber-steroids, keeps making my (Richard) theo-sense tingle. There's a lot here about incarnation: creators entering "the Grid" they've developed, and trying to fix bugs in the system. In the original, the liberation theology was evident, as the programmer Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges) entered the universe he'd created and sacrificed himself for it—only to be "resurrected" back into the real world. In the sequel, there's fodder for process theologians, as we see Flynn's son arrive to correct an error in his father's creation. Finally, there are some apocalyptic elements, even if they are Hollywood trite.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 1

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 1

A theme that has been present in the Harry Potter series since the beginning is an embrace of death as an inevitability, and indeed, part of what gives life value. As Dumbledore says in the first Potter book, "After all, to the well-organized mind, death is but the next great adventure." Furthermore, over the course of the story arc, it becomes clear that Voldemort's Achilles heel is not simply a lack of love but an egomaniacal drive to conquer death, both out of fear and a desire to become the most powerful force on earth.

The film and book versions of Deathly Hallows resonate with Paul Tillich's The Courage to Be. In Tillich's view, one cannot even begin to have faith—in God, or Jesus, or heaven, or anything—until one has experienced the angst of mortality. We find a perfect example of this in Jesus' choice of the cross, knowing full well the great cost of mortality. He understood both the cost and the value of letting go of his life. Harry not only understands this but, as we will see, lives it too.

For longer critiques on the films above, visit the original article at www.poptheology.com.