From the start, Italian Catholics have played key roles in American history: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot, Giovanni da Verrazzano, Amerigo Vespucci. But it was a long time before Italians came here in large numbers. In 1851, the City of New York had seventy-four Italian residents; by the turn of the century it had more than Genoa, Florence, and Venice combined. By then Italian immigrants were arriving at Ellis Island at the rate of 100,000 a year.

From the start, Italian Catholics have played key roles in American history: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot, Giovanni da Verrazzano, Amerigo Vespucci. But it was a long time before Italians came here in large numbers. In 1851, the City of New York had seventy-four Italian residents; by the turn of the century it had more than Genoa, Florence, and Venice combined. By then Italian immigrants were arriving at Ellis Island at the rate of 100,000 a year.

To understand why, we must look back to Italy, which had just moved from a series of independent kingdoms into a united nation. (The popes, who for centuries ruled central Italy, opposed it.) When Italian troops entered Rome on September 20, 1870, unification became official. In a fit of anger, Pope Pius IX banned Catholics from participating in national politics. The ban lasted for decades.

But poverty was widespread in southern Italy, the mezzogiorno, and it would get worse. After visiting this largely rural area, Booker T. Washington, a former slave, commented: "The Negro is not the man farthest down." High taxes didn't help, nor did economic unrest, rising prices, and growing unemployment. Immigration seemed to be the only choice.

But to get to America, many needed help—a patron (padrone) who paid their passage and got them a job. Often immigrants themselves, these provided room and board, collected wages, and gave workers an allowance. They also exploited immigrants through a system that wasn't fully eradicated until well into the 1900s.

The newcomers didn't call themselves Italian, but Neapolitan, Calabrese, Genoan, or Abruzzese. While early Italian immigration was mainly northern, after 1880 it was almost completely southern. Cultural differences ran deep. A priest from Tuscany, assigned to a largely Sicilian parish, asked in exasperation what manner of people his parishioners were.

The men came first. Most planned to return once they made enough money. Like the Irish, they settled mainly in cities where they found work. (Some immigrants assumed that New York was a very religious place, since the street signs read "Ave.") "Little Italies" formed in cities nationwide, but also in some unexpected places, like Salt Lake City, Omaha, Tontitown, Arkansas and Morgantown, West Virginia.

America changed Italians in more ways than one. Ellis Island clerks, unable to pronounce or spell their names, changed them arbitrarily on the paperwork. A Benedetto became a Bennett, Pascuzzi was rechristened Pascoe, and Randazesse was renamed Randa. One clerk renamed a young man O'Neill. He later studied law and became a judge in Philadelphia, where his "Irish" connections played a factor in his rise.

Local Catholic reaction to newcomers was mixed. New York's archbishops made outreach a priority. In Manhattan, Sister Catherine Seton, daughter of the first American-born saint, studied Italian in her 80s to better help them. In the Bronx, Father Daniel Burke, fluent in Italian, started St. Philip Neri Church. In Greenwich Village, heiress Annie Leary kept Our Lady of Pompeii Church afloat during its early years.

But there was also Bernard Lynch, who in 1888 wrote an article for the Catholic World complaining that his neighborhood was "invaded" by "dark-eyed, olive tinted men and women." He asked whether they could ever assimilate. There was Paul Boyton in Coney Island, who asked his bishop to replace the Italian pastor with an "American." And there were Irish priests who relegated Italians to the basement, the chiesa inferiore.

Much of the Irish-Italian conflict was based on different religious styles. One stressed institutional affiliation, while the other simply emphasized being a Cristiano. Although clergy bemoaned their lack of formal religious education, Italians had a definite religious worldview. One scholar calls it a "distillation of the lives of saints, stories of miracles, and some prayers, along with protective incantations, passed down from generation to generation."

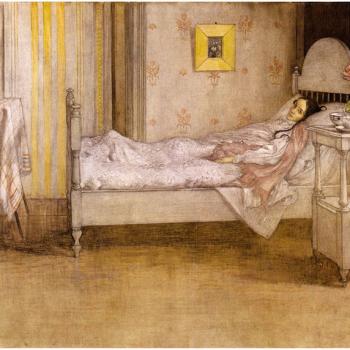

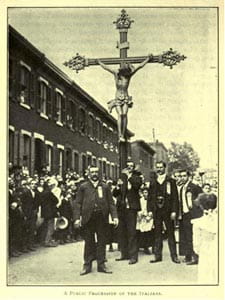

Nowhere was their religious life more publicly expressed than at their festivals. Food, games, and music attracted thousands, but these were incidentals. Ultimately, the purpose was to honor the saints who guided and protected the people. In his 1943 memoir Mount Allegro, Jere Mangione writes:

A guardian saint was like a friend in court. He had special access to God's ear. If you took care to remember the saint with prayers and an occasional candle, you could usually count on him to remain loyal and carry out your wishes.

In New Orleans, once home to a large Sicilian community, the Feast of St. Joseph (March 19th) is still a major event. Neapolitan immigrants began Manhattan's San Gennaro Festival (September 19th). Each summer, New York City hosts three separate festivals for Our Lady of Mount Carmel (July 16th). Its founders, Robert Orsi writes, wanted to honor the Madonna who "consoled them during the trials— both physical and spiritual—of immigration."