One day while I was driving with my daughter McKenna, she said, "Dad, I love you." I reached over and clutched her leg, as I always do. Then I heard even better words: "I also like you a lot." Most parents would give their left thumbnail to have their kids respect, revere, and honor them. Nothing's wrong with that, but there's something even better: their desire to be with you and possibly to be a little like you.

If you let it, that's where sacrilege is going to take you.

People revered Jesus back then, and many still do today. No, not everyone, but some pretty significant masses still think he's the most inspiring man to have walked the earth. We have to remember that back in Jesus's time, before they really knew who he was and what he was doing in the world, the average Jacob and Martha liked Jesus. Similar to when you meet a person you click with at a party, they were amazed at his accessibility and his acceptance of everyone. Notice that the people who did not like Jesus—the Pharisees, for example—were people in power. Common folk couldn't get enough of him, though. They were surprised by his candor, honesty, riddles, and wit. They marveled and were sometimes even intimidated by his blatant disregard for the rules and regulations of the day, although they must have secretly loved it. I often imagine the children sticking their tongues out at the disciples, who had tried to shoo them away, as they sprinted toward the open arms of Christ.

His ways would have flown in the face of many who tried to control and oppress the people through religious legalism. Yet, at the same time, they must have felt a gentle prick in their conscience when he seemed to disregard or even condemn their traditions and spiritual viewpoints. As Jesus continued to teach, he not only tipped their sacred cows—he slaughtered some.

If you could have been a contemporary embedded reporter getting on-the-ground quotes from those who were following Jesus, you might have heard (Americanized) statements like these:

"Did you see the look on those punk Pharisees who were getting ready to chuck a rock at that whore when Jesus stepped in and made them back down?"

"Wasn't it awesome that he was willing to heal Claudio and Melpis on the Sabbath?"

"Can you believe he picked Peter, Andrew, and John to be his students? Heck, they're just fishermen. You don't have to have many credentials to get in good with this guy, eh?"

"Don't you think it's kind of weird that Jesus spends so much time with women, especially that Mary chick? I wonder if his motives are as pure as he claims."

"Have you recovered from the wedding feast this week? Sheesh, I was pretty done, but when Jesus made more wine, I just had to keep celebrating. That was quality vino!"

"You know what's most amazing to me now that he's come back from the dead? I knew him when he was twenty-one, just working in his dad's shop. He never said a word about who he was. I remember a deal he gave me on the chair I bought for my mother. Great chair too!"

This is why the early followers got to the point of no return with Jesus. They were drawn to him, followed him at great cost, and spoke endearingly about his legacy on their lives. They viewed him as if he were a god—and that's exactly what he was: the one true God.

His first and earliest followers got to experience both his strange divinity and his impressive humanity. We don't. We have to read between the lines. From the time of Jesus and the apostles until now, the church has lost so much influence, especially among normal, everyday people. What happened? We have missed something—something huge.

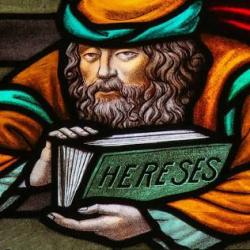

We have blandly imagined Jesus to be a little icon of a man we hang on chains around our necks and whose image we use in stained glass windows. We salute him when we score a touchdown or hail him when we win a Grammy Award for our raunchy rap song. We put him on T-shirts and bumper stickers. We write sappy teenage pop songs that make him sound more like a groping boyfriend than the Creator of the universe. We market him; we exploit and misuse his words to browbeat, judge, and injure the world. And in the name of "discipleship," we gather every week to reread his words, often, sadly, without giving much serious thought to becoming a smidgen more like him.

It's no wonder people today have had to conclude he's just another man who happened to start a prolific religious sect. But it's time to say it: he wasn't trying to start a religion! He wasn't trying to put a church building on every corner. His highest hopes were not that millions of people would gather on Sundays to enjoy learning doctrine about his moral codes. He doesn't care if you are a Republican or a Democrat, but he does care that much of the world is turned off by millions of people who claim him as their leader.