The word “advent” comes from a Latin term, which means “coming”—as in the “coming of Christ.” Thus, the four-week season of Advent (starting at the end of November and continuing until December 25th) takes its name from its dual focus on Jesus Christ’s two “comings”—namely, His “First Advent” (or birth) and his pending “Second Advent” (often referred to as His “Second Coming”). Accordingly, the first two Sundays of the Roman Catholic liturgy (in December) focus on the anticipated return of Christ (or His “Second Advent”), and the last two Sundays of December place their emphasis on Jesus’ incarnation (or birth), with the fourth Sunday also highlighting the Virgin Mary’s role as the Mother of God or Theotokos (as Orthodox Christians call her).

Who Celebrates Advent?

While Advent has been commemorated in some form or other since as early as the fourth century, it is more commonly and formally celebrated by High-Church traditions, like Roman Catholicism, Anglicanism (and Episcopalianism), Lutheranism and, in its own unique way, Eastern Orthodoxy. While there are many Low-Church denominations that acknowledge the Season of Advent (such as some Evangelicals, Baptists, and Non-denominational Christians), the liturgical component is largely absent in these Low-Church traditions. And yet, because the “Christmas Season” is synonymous for many with Advent, perhaps many inadvertently commemorate Advent, unaware that the one “season” is really part of the other.

What are the Origins of Advent?

Of course, many Christians are familiar with Advent—at least in a general sense. However, few will be familiar with the history behind this annual holiday. As noted, it can be traced back to at least as early as the fourth century—though it wasn’t until the 6th century that Pope Gregory the Great formalized the Advent Season. Indeed, he is the one that officially established the four-week “Season” of Advent; and it was Gregory who composed many of the authorized prayers, antiphons, and responses to the recited psalms utilized by Roman Catholics during the four-week advent season.

Prior to Pope Gregory’s efforts with regards to the holiday, the First Council of Saragossa (AD 380)—a Catholic council of Spanish and French bishops—gathered to condemn the heresy of Priscillianism. However, as part of the council’s decrees, they issued a statement reminding Christians that they were duty bound (“commanded,” as it were) to attend Mass daily from December 17th through January 6th. This set apart much of the Advent Season as a sacred time of the year.

While many Christian denominations reserve Easter as the season for baptism and the entrance of The origins and meaning behind the Christian holiday of Advent, its historical roots, biblical significance, and how it is celebrated across denominations and cultures. into the faith, there was a time in the history of the Church when Advent was the period when those converting would become Christians. This was particularly common among Christians in Spain (in the late 4th century). During that period, Spanish Catholics saw Advent as the period to prepare catechumens for baptism, which were then performed on January 6th (which is Epiphany in Roman Catholic tradition).

As a possible outgrown of Pope Gregory’s influence, the Second Council of Tours (AD 567) and the Council of Mâcon (AD 581) both prescribed or, in the case of Mâcon, ordered fasting for clergy as part of the Advent Season. Those who had taken holy orders were to fast three times a week during the period between Martinmas (or the November 11th Feast of St. Martin) and Christmas day. Much like Lent (leading up to Easter), some faithful Christians will essentially Lent during Advent as well, either abstaining from meat on Fridays, or limiting the intake of other things (like sweets, alcohol, or even shopping and screen time).

The fasting component of Advent was originally associated with the season as a time of penance, perhaps in part because of the preparation of the catechumens for baptism. However, today the focus is more on the joy of the season and the hope for Christ’s return and the “better days” ahead.

Why is Advent important?

While one might question the “importance” of Advent, particularly during a time when many have moved away from organized religion, nevertheless, in actuality this may be the very reason the Advent Season is important. In an era when Christmas is remarkably secular and commercialized, what Advent does is to remind the Christian of why this holiday exists. It is a weekly and even daily reminder of Jesus’ two Advents—His incarnation and His coming return.

Thus, Advent was established with a focus that would meet the needs of a significantly secular society many centuries prior to its secularization. In the same century that the First Council of Nicaea was held, inspired Christian leaders saw a need to establish a holiday that would prepare “believers” for the two advents of Christ. In essence, the Advent Season (established nearly 1,600 years ago) foresaw a time when the “true meaning” of Christmas would be lost.

This holy holiday is a great daily reminder to Christians of what their focus should be during the month of December—not on the worldly or commercial trappings of the season, but on the meaning of Christ’s birth and the impact of His return.

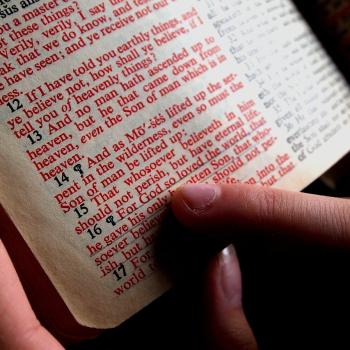

What Biblical Passages Shape our Understanding of Advent?

The most famous passage in the Bible, read by many during this time of the year, is Luke 2, which is the traditional nativity narrative. Second only would be Matthew 2 which (as Paul Harvey would say) tells “the rest of the story” of the Nativity. Whereas Luke focuses on the shepherds (to whom an angel appeared) and the birth of Jesus and His placement in a manger (or feeding trough); Matthew tells us the details about the “new star,” the Magi (or “wise men”), the massacre of the infants (as ordered by Herod), and Joseph’s prophetic dream that he needed to take the young Jesus and His mother and flee to Egypt.

Other important biblical passages, often incorporated into the liturgies of various Christian traditions (during Advent), include the following:

- Isaiah 9:2-7—which is a notable Messianic prophecy that includes the line (Handle lifted for his famous oratorio), “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace.”

- Isaiah 40:3—also a Messianic prophecy, foreshadowing the mission and words of John the Baptist, “A voice cries out: ‘…prepare the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God.’”

- Micah 5:2—which prophetically foretells Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem: “Bethlehem…, you are one of the smallest towns in the nation of Judah. But the Lord will choose one of your people to rule the nation—someone whose family goes back to ancient times.”

- Isaiah 7:14—another of the most well-known Messianic prophecies of Jesus’ birth: “Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a Son, and shall call His name Immanuel” meaning “God [is] with us.”

How is Advent Celebrated?

The way in which the Advent Season is celebrated really depends on one’s denomination, cultural practices, and even family traditions. For instance, one reared in the Evangelical tradition might not place nearly as much emphasis on Advent as a practicing Roman Catholic. Each denomination and each family are different. There are certain commonalities surrounding the season, but also many inconsistencies.

As an illustration, many in the High-Church traditions have a very set liturgy that is used during this time of the year, though Low-Church Protestants usually do not. Similarly, in certain traditions, purple vestments would be worn by priests during Advent. For others, however, liturgical vestments are not part of their tradition. While some denominations have set scriptural readings for the Advent Season, others really only focus on Luke chapter 2 and, to a lesser extent, the second chapter of Matthew.

Some individuals fast during Advent, while others see it instead as a time of feasting. In other words, Advent commemorations differ greatly. Here are a few popular practices that are not necessarily denominationally driven:

- Advent Calendars—While these come in many forms (including ones with candy or a toy for each day), they are essentially a way to count down to Christmas itself. Having their origins in Germany, 19th century Protestants would burn one candle each day leading up to Christmas or, in some cases, keep a tally of the days on the door to their houses, making a daily mark with chalk or other removable substance. The first physical actual “calendar” for commemorating the Advent Season dates to around 1851.

- Advent Wreaths—These are often decked with candles (usually 4), symbolic of the light Christ brought into the world and the salvation He offers believers. The green color and the circular shape are commonly seen as symbols for the hope of eternal life that Jesus makes available through His life and Ransom Sacrifice.

- Christmas Trees—These have similar symbolic connotations as an Advent Wreath but, today, are much more common, and have taken on a more secular meaning, though their original symbolism was essentially the same as the Advent Wreath.

- Special Church Services—While these vary from denomination to denomination, other than groups like Jehovah’s Witnesses or Church of God (Seventh-Day), most Christian denominations have some special service(s) to commemorate the season. That may just be on the Sunday closest to Christmas, or those special services may occur on each of the four Sundays of Advent. Regardless, they usually include music (songs or hymns) sung mainly during that season, specific readings from the biblical text clearly associated with one or both of Christ’s Advents, and the employment of traditional holiday apparel and decorations as well.

Conclusion

Properly celebrated, Advent attests to the reality of the incarnation (as celebrated at Christmas), and encourages a hopeful optimism about Jesus’ Second Coming (which is said to be accompanied by the destruction of all that is evil). Advent is a holy season that once stressed repentance but is now more of a holiday of hope.

Symbols so commonly secularized in Advent celebrations of our day were originally seen as Christ-centered and sacred: things like evergreen trees (for eternal life), the use of the colors red (symbolic of Christ’s shed blood) and green (a representation of the everlasting life He offers), the employment of lights (for Christ’s Spirit), and even Christmas gifts (associated with the gifts brought by the Magi, but even more as symbols of the gifts offered to believers through Jesus Christ).

Advent might seem less like a holiday and more like a “season,” even the popular “Christmas Season.” However, its original intent really seems to have been one of preparation—preparation for commemorating what it means of have had the Son of God born, walk the earth, and ultimately die to atone for the sins of all. But also, preparation for the return of Christ, His “Second Advent” or “coming.” As we contemplate the holiness of His life during that first coming, we’re reminded (at Advent) of how our own lives should reflect that same holiness so that, “when he shall appear, we shall be like him” (1 John 3:2)—and be able to dwell with His for eternity.

12/5/2024 1:06:00 AM