“I wonder what it would be like to fast in Siberia,” my friend Mohammed asked.

Mohammed had always enjoyed Ramadan in the company of family and friends in Jordan — a Muslim-majority country in the Middle East. He was curious what it might be like to fast in places where Muslims were in the minority or where daylight hours extended late into the night, extending the fasting period beyond the limits he was used to.

According to Islamic tradition, fasting is required during Ramadan, the ninth month of its lunar calendar. In 2022, Ramadan is likely to start on April 2. For thirty days, those fasting are obligated to abstain from drinking, eating, or engaging in other indulgent activities (like sex, smoking, and activities considered sinful) from just before sunrise to sunset. Depending upon where you are in the world, that can mean fasting 10 or up-to-21 hours. It was the idea of fasting for such a potentially long time that prompted Mohammed’s ponderous question about fasting in Siberia.

Muslims are far from the only religious actors who fast. Bahá’ís fast during daylight hours during the first three weeks of March in preparation for the Naw-Rúz Festival. As this post goes to press, Christians the world over are still in the midst of their Lenten fasts and looking forward to Easter. Some Hindus regularly practice fasting as a means of willful detachment and devotion.

With such a wide range of similar aesthetic practices, one might be tempted to assume that fasting shares some unified purpose among the world’s religious.

Yet, there are also numerous “secular” — or professed non-religious — examples of fasting to consider as well. Whether it be intermittent fasting for weight loss or fasting for political purposes or justice causes, abstaining from food, drink, and other bodily needs and pleasures is not limited to the domain of the nonmaterial.

Indeed, fasting is decidedly physical and material.

That’s enough reason to begin to wonder if fasting is less about spiritual discipline and inner contemplation and much more about external, if limited, factors of control and community connection.

Why Do People Fast?

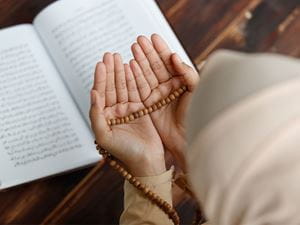

If you ask religious actors why they fast, you’re likely to hear that they abstain from food, drink, and other pleasures as a means of devotion, discipline, or meditation.

Talking to Teresa, a Baha’i in Chicago, I was told that she fasts to “focus more intensively on spiritual matters” through “physical detachment” from distracting desires and passions.

Instructing Christians that “fasting must forever center on God,” the Quaker theologian and contemplative Richard Foster advised that fasting “reveals the things that control us” and can help bring our chaotic lives back into balance. In the Spiritual Disciplines Handbook, Adele Ahlberg Calhoun wrote that fasting is about “self-denial” in order to cultivate prayer and as a “reminder to turn to Jesus who alone can satisfy.”

Mohammed said his Ramadan fasting is about giving up food and drink to grasp a greater awareness of the presence of God and gratitude for God’s daily provision. The challenges of fasting — hunger, irritability, fatigue — are a means of testing his faith and amplifying the possibility of achieving greater taqwa, or God-consciousness. While fasting is encouraged at other times, Ramadan multiples fasting’s spiritual benefits (thawab) and, he said, “the opportunity to break the fast every evening with family and friends is a great opportunity to celebrate this fact.”

Though with different ends or emphases, religious actors generally share the base assumption that fasting from physical pleasures is a means of deepening spiritual discipline and, eventually, delight. Whether as a symbol of death and rebirth, penance, or pious humility, those that fast for religious purposes tend to interpret the blessings, burdens, and benefits of fasting as inner and intangible.

What Do Scholars Have To Say?

Scholars of religion have generally gone alone with religious actors’ interpretations of fasting.

For example, in keeping with his general tendency of discerning the different meanings and motivations ascribed to acts, anthropologist Clifford Geertz determined that while dieting is tied to the material world, religious fasting carried with it an innate and intangible “freedom.”

Sociologist Max Weber believed fasting is a means of maintaining social connections and simultaneously revitalizing them. In the Weberian tradition, others have viewed fasting — and its related feasts — as means of supporting societal — or even cosmic — cohesion.

Tantalizing enough, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche viewed fasting as an attempt to control the world around us. Nietzsche saw fasting as a coping mechanism to constrain or gain command over internal chaotic emotional states. For Nietzsche, fasting was a way to make our deep anxieties more manageable and rein in our seemingly untamable uncertainties about the world.

Despite these attempts to extend the meaning of fasting to our material contexts and social worlds, interpretations consistently defer to inner interpretations or internal impulses to explain its surprising appeal and persistent popularity among the world’s religious.

At the same time, I can’t help but think of the inherently material and physical nature of fasting points to alternative interpretations of its power and meaning.

In a context generally gluttoned with fast food and readily available indulgences thanks to the advances of global capitalism, I wonder if fasting could be seen as an act of resistance against the greed and immediately gratified individualization this system readily encourages.

Constrained, or rather not constrained, by capitalism’s plenties, fasting might be viewed as a means of stepping outside — or perhaps beyond — them. From this perspective, to reject physical pleasures in favor of what we believe to be inner, or eternal, promises is a way to reject — or simply try to resist — the forces we feel that confound, curtail, or control us.

What Would it Be Like to Fast in Siberia?

And yet, this explanation cannot cover the wide variety of historically, regionally, and religiously specific practices of willing abstention from food, drink, and other physical pleasures.

As with other beliefs, actions, and rituals that we examine when studying religion, there is no way to reduce the sheer variety of expressions across various traditions — even though they seem shared — to any single narrative or explanation.

Which brings us back to my friend Mohammed. His desire to fast in Siberia could be seen as one part curiosity, another part wanderlust. It could also be seen to magnify and reinforce how Ramadan’s fasting and feasting helps him feel in control and connect with others in a chaotic world.

At the same time, his question could serve as a provocation.

•What would it be like to fast in Siberia?•Would Mohammed’s practices and perspective change?

•Would the claims he makes about fasting and its purpose shift?

•Would the fasting itself be fundamentally different in feeling and effect?

These are questions not only for Mohammed, but for the student of religion as well.

Before we can begin to understand things like fasting, we must first ask ourselves what historically contingent and contextually situated factors are at play as we try to make sense of such practices.

Indeed, before we ask if fasting is about religious people trying to make sense of a chaotic world, we should ask ourselves if our attempts to compare fasting across different traditions, times, and places is a means of exerting control on a diverse range of practices that share some superficial ascetic similarities.

Taking a page out of Mohammed’s ponderous book, we might begin by asking about what limits, interests, debates, and experiences inform actors’ fasting. Then, we might begin to better appreciate the why, what, and how of this decidedly popular — if decidedly difficult — form of ritual performance.

11/29/2022 11:34:25 PM