At the end of last year, the uptick in antisemitic and Islamophobic incidents in the U.S. and around the globe captured headlines as part of the fallout from the Israel-Hamas War.

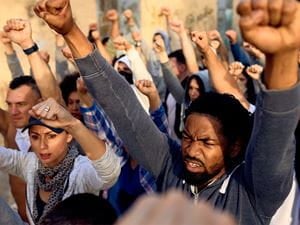

Reactions were swift and widespread, as university presidents resigned, demonstrators took to the streets in places like Berlin and Paris and the White House promised to take steps to curb religious and faith-based hate in the U.S.

The topic of rising discrimination and incidents of hate remains contentious, as debate over definitions and political polarization challenges us as we try to understand the issues.

As students of religion, it is important to exercise caution when approaching these hot-button issues. Hot takes are not helpful. Instead, students of religion should carefully observe the debates, examine the variegated histories and definitions of the terms, and uncover both antisemitic and anti-Muslim hate’s cultural, political, and ideological antecedents.

Worrying Statistics

The statistics are worrying, to say the least, with pronounced upticks in both antisemitic and anti-Muslim incidents since Hamas' attack on October 7, 2023, and Israel's subsequent invasion of Gaza.

According to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), antisemitic incidents increased by 388% in the U.S. in the four weeks following the attack. And in a new report by the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), the Muslim civil rights and advocacy organization said it received a total of 1,283 requests for help and reports of bias between 7 October and 4 November -- a 216% increase.

In a call with reporters, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) said they saw an increase in threats against both Jewish and Muslim communities. Although not providing specific numbers, FBI director Christopher Wray told The New York Times that they feared further hate-based violence in the U.S., like that of the October 15th fatal stabbing of 6-year-old Wadea Al-Fayoume, 6 at his Illinois home in what police said was an anti-Muslim hate crime.

Swelling statistics were also noted in Europe, with the United Kingdom and Germany both reporting increases in antisemitic and Islamophobic hate. For example, the British organization Tell MAMA received a sevenfold increase in reports since early October and UK police documented a sharp rise in antisemitic hate crimes. Moreover, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) reported a 43-fold increase in anti-Muslim YouTube comments.

These reports do not even capture the full extent of anti-religious hate, with the targeting of individuals at work and school, assaults on sacred spaces (e.g., graffiti on mosque walls, eggs being thrown at local synagogues) as well as online abuse often going unreported.

Definitions Matter

These reports also raise the questions of definition. How do these various institutions and agencies define antisemitism and Islamophobia? Definitions matter, because they establish the baseline and boundaries of what gets counted as an act of hate — or not.

But definitions are also a matter of debate. Legal experts, scholars, governments and editorial staff have wrestled with how to establish the nature, scope, and meaning of antisemitism and Islamophobia over the years. And the disputes about what counts as anti-Jewish or anti-Muslim hate and prejudice are far from over, playing a role in courtrooms, politics and in public opinion.

Antisemitism, at its most fundamental, is prejudice or discrimination against Jews.

Although most scholars agree on the above, there are broader interpretations, like that of the Berlin-based International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. Their definition includes the singling out of Israel and the demonization of its character, which led the German government, for example, to declare, "the state of Israel, being perceived as a Jewish collective, may be the target of [antisemitic] attacks." Critics say that these broader definitions are unclear about "the boundary between legitimate criticism of the actions of the Israeli government and Israel-related antisemitism."

Originally, the term Islamophobia was coined to call out anti-Muslim sentiment in the West, evolving into a political concept and analytical category to identify anti-Islamic/anti-Muslim rhetoric and actions across time and in a range of social, political, cultural and geographic contexts.

In 1997, the British think tank, the Runnymede Trust, published the report "Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All," which is widely credited with introducing the term “Islamophobia” into public discourse and providing one of its first, comprehensive definitions: Islamophobia refers to unfounded hostility towards Islam. It refers also to the practical consequences of such hostility in unfair discrimination against Muslim individuals and communities, and to the exclusion of Muslims from mainstream political and social affairs.

The Trust's report included criticism of the term, with some saying it pandered to political correctness or that it stifles legitimate criticism of Islam. Others believe the term is best "understood through registers of race," so that it has also been defined this way: “fear, hostility and hatred of Muslims or Islam that is rooted in racism and that manifests itself in discriminatory, exclusionary and violent practices targeting Muslims and those perceived as Muslims.”

When trying to describe the phenomena we see in headlines or on college campuses, words should be chosen carefully. Students of religion should be aware of these debates and approach both with balance and an understanding of the deep hurt, trauma and sense of injustice involved with words, acts and structures of discrimination and bias.

Be sure to discuss the distinctions between, and historical antecedents of, each term. Where appropriate, acknowledge debates over the definitions in order to bring more depth to your understanding. Above all, bring necessary nuance the discussion, avoid stereotypes and provide examples, rather than just labels. For example, rather than labeling someone or something antisemitic, be specific in providing concrete details or examples from an individual’s or institution’s words or actions.

The Long Arc of “Other” Hate

Despite the worrying increases in the last few months, antisemitism and Islamophobia have been simmering and showing up for decades, if not centuries.

A year before the attack and subsequent invasion in October 2023, Germany’s Department for Research and Information on Anti-Semitism (RIAS), documented 2,480 incidents across 2022. According to German police, that number was 2,032 in 2019, including a deadly synagogue attack in the eastern city of Halle. In 2010, there were 1,268 such incidents. In other words, antisemitism has been on the rise for the last few years.

The roots of this uptick in attacks and anti-Jewish rhetoric are complex, and include a mix of right-wing political extremism, the influence and appeal of global antisemitic rhetoric on the internet, and conspiracy theories surrounding current events like the pandemic and the Israel-Palestine conflict.

For Muslims in Western countries, the recent spike in hate recalls the steady stream of Islamophobia that has been a consistent presence in their lives since 9/11.

Indeed, while it may be convenient to blame rising antisemitism and Islamophobia on recent events, there have been cycles of increased hate that reveal a long-held pattern of “Other” hate against Jews and Muslims in Western contexts.

For example, while reporting on 1,700 years of Jewish history in Germany, I came across an equally long legacy of Christians opposing Jews and the dangers allegedly emanating from them as an outgrowth of their faith and praxis. Over thousands of years, this “anti-Judaism” produced a vast storehouse of anti-Jewish literature, art, and folklore throughout the Western world, especially in Europe, including everything from church sculptures to popular plays and the attempt to de-Judaize music.

And, in my research on Islam and Muslim communities in the Americas, I came to appreciate what anthropologist Alejandro Escalante calls “the long arc of Islamophobia” — or how anti-Muslim bias in the Americas stretches back across the Atlantic to places like medieval Spain and Africa through the transatlantic trade in enslaved persons.

In other words, both antisemitism and Islamophobia are not recent phenomena. They are not the result of recent headlines nor solely to be blamed on particular groups. Nor are their current amplifications anomalous in Western nations when viewed against the long history of anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim language, laws, movements, and popular culture.

Before Coming to Conclusions

For students of religion, it is important to not get too caught up in the headlines. Yes, statistics are worrying. Yes, as global citizens, we have the responsibility to defend the human rights of others.

But before we rush to judgment or come to swift conclusions about why these escalations are happening, who is to blame for them, and how we might address them, we need to situate the statistics within broader political, social, ideological, and cultural debates and histories.

The above was a brief attempt at doing so. But I am convinced that if hate speech and acts are to be stymied in our time, students of religion must begin by critically studying their antecedents and broader situatedness in the societies where they are most vociferous.

2/7/2024 1:27:59 AM