For Ruben Garcia, executive director of the under-fire Annunciation House in El Paso, Texas, the 2024 elections are critical when it comes to immigration at the U.S./Mexico border. Up and down the ballot -- at the federal, state and local level -- Garcia said faith leaders like himself, especially given the legal threats his organization is facing in Texas, are concerned about the outcomes.

“I want people to understand these politicians are people we are voting for and putting into office. They believe they can use the law to go after people in a way that degrades others’ humanity,” he said. “You absolutely need to look at who you’re voting for.”

Polls show that immigration is a primary concern for many voters ahead of November's presidential election.

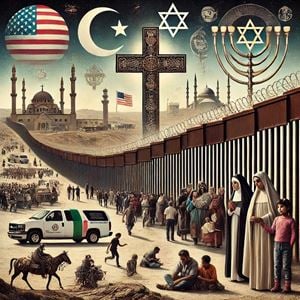

And I’ve seen this firsthand, reporting on faith and immigration over the last six months. I traveled to Tijuana, Mexico, Lampedusa, Italy, southern Arizona and downtown Los Angeles to hear from migrants making their way. I heard from Muslim aid workers on the front lines providing sanctuary and nuns serving the vulnerable asylum seekers living on the streets of Skid Row. I sat with mothers weeping over their children and praying for safe passage at a cemetery just meters from the bollard-steel border wall that rips through the Sonoran wilderness like a rust-colored wound.

At each stop, I witnessed the centrality of religion to the story of immigration and how immigration to the U.S. fits within a more global story of human movement and migration.

At the same time, I’ve also seen how religion shapes our responses to immigration and its politics, with some evangelicals calling for comprehensive immigration reform even as others are drawn to more nativistic or anti-immigrant rhetoric and sectors of society question the motivations of a shelter for Muslim migrants along the border.

Religion on the move

The intertwined phenomena of religion and migration have long been mutually reinforcing — and mutually complicating.

People move internationally for many reasons, as the Pew Research Center shares: “to find jobs, get an education or join family members. But religion and migration are often closely connected.”

That is why, as a general rule, I find it vitally important for students of religion to pay attention to the overlap between religion and immigration. But in this present historical moment, when immigration is a key issue on ballots in the U.S. (and Europe, for that matter), it is perhaps even more critical to understand how the two are related.

In particular, I think it is important to cast the present political and historical moment into the context of global migration across time.

Religion, as I often tell my students, has always been on the move. Religious ideas, people, technologies, practices and capital have long transcended boundaries and borders — between empires, through and across continents, to the other side of the seas.

Migrants throughout the ages have moved to escape religious persecution or to live among people who hold similar beliefs. Others have moved for economic opportunities or because they were forced to leave home.

Whether it be the Hebrew people fleeing Egypt via Sinai on their way to Palestine, Asian immigrants introducing Buddhism to California in the 19th-century, African traditional religions taking root in the Americas via the Transatlantic trade in enslaved persons, or the muhājirūn (Muslim emigrants) fleeing Mecca to Yathrib (Medina) and Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in the 600s C.E., religious adherents have been pushed and pulled across land and oceans, creating transnational linkages and networks that span continents and centuries.

According to an August 2024 report by the Pew Research Center, more than 280 million people, or 3.6% of the world’s population, are international migrants. Of those, Christians make up a much larger share of migrants (47%) than they do of the world’s population (30%). Mexico is the most common origin country for Christian migrants, and the United States is their most common destination.

But Jews are most likely to have migrated, with one-in-five Jews residing outside of their country of birth.

Muslims account for a slightly larger share of migrants (29%) than of the world’s population (25%). Syria is the most common origin country for Muslim migrants, and Muslims often move to places in the Middle East-North Africa region, like Saudi Arabia.

People without a religion make up a smaller percentage of migrants (13%) than of the global population (23%) — China being the most common origin country for religiously unaffiliated migrants and the U.S. their most common destination.

Hindus, however, are starkly underrepresented among international migrants (5%) compared with their share of the global population (15%) and Buddhists make up 4% of the world’s population and 4% of its international migrants, with Myanmar (also called Burma) their most common origin country and Thailand their most common destination.

Immigration impacts religion

As religions move, they change. They are adopted by new communities and adapted to new contexts.

People move and take their religion with them, contributing to shifts in their new country’s religious dynamics. At the same time, migrants may leave the religion they grew up with and adopt traditions and identifications in their new host country — some other religion or no religion at all.

In the U.S., we have been watching how immigration from the Global South (e.g., Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa) has transformed — and continues to alter — the nation’s religious landscape. Alongside an increasing secularization is a concomitant pluralization, brought on by the introduction and proliferation of religious traditions like Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam. Immigration is also impacting Christianity’s demographic make-up, with the “de-Europeanization” of U.S. Christianity proving just as significant as the “de-Christianization” of the country as a whole. The Catholic Church is becoming increasingly shaped by Latinx members and currents and evangelicalism by Pentecostal/charismatic varieties from practitioners in places as diverse as Brazil and Nigeria.

Meanwhile, in European contexts like the Netherlands, researchers have found that while “immigrants’ religious practices increase in the first years after arrival” that increase “eventually levels off and even reverses with increasing length of stay.” Across religious groups, whether they be Muslim, Christian, or otherwise, there is a decrease in religious identification over time, suggesting that all immigrants in Europe are “susceptible to the secularizing forces of the receiving society.”

In these respects, migration has been and continues to be an important factor in religious change, innovation, and pluralization.

Beliefs, Identities, Immigration

Religion motivates migrants to move. It shapes our responses to immigration and its politics. The intersection between the two is nothing new and their mutually complicating dynamics are part-and-parcel to a broader story of human movement across time and space.

So, as we head to the polls in the weeks and months to come, it is important to keep these factors in mind. Keen students of religion would be wise to interrogate commonly offered justifications of particular policies based on certain “beliefs,” “identities,” or “communities.” Likewise, they should critically analyze sources that report or comment on immigration and religion, keeping in mind the above history and contemporary dynamics as they do so.

The hope, to riff on Garcia’s words, is that people will think about how religion might be a key aspect to understanding the broader context of who, and what, they are voting for when it comes to immigration.

9/3/2024 9:12:50 PM