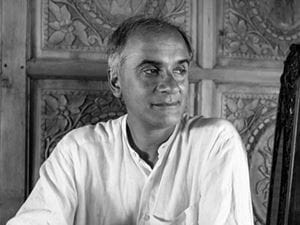

The term “global citizen” could have been invented to describe Pico Iyer, the best-selling travel writer. Born in Oxford, England, to Indian parents, he was educated at Eton, Oxford, and Harvard. In his late twenties, Iyer gave up a comfortable life in New York City to move to Japan, where he married and has lived ever since. Few writers have captured the spirit of the age better than Iyer. None have matched his attentiveness and nuance to matters of soul and spirit. As Iyer explains in this interview with Patheos’ editor at large, his interest in religion essentially begins at birth.

Religion and spirituality have been consistent threads in your work for a long time. How do you account for your interest in matters of the soul?

Those matters seem the most essential of all, and the older one gets, perhaps, the more one sees that they might be worthy of even more consideration than Brad Pitt or the Kardashians. One's house burns down, one falls in love, one's daughter, at thirteen, is diagnosed with Stage 3 Hodgkin's Disease, one gets silenced by beauty, and it's hard not to feel that the most important things in life are the ones that can never be caught by words or ideas, let alone headlines.

You could say, on a practical level, that both my parents were philosophers who were professors of comparative religions; they'd been trained in the Bible in British India, they were Hindu-born Theosophists, and they were so close to Buddhism that I was receiving a photograph sent to me by the Dalai Lama when I was three years old. As a little boy, I'd step into our living room in Oxford to find it filled with Tibetan monks in red robes, an unusual sight in those days.

And since I was growing up in English boarding-schools, I had to go to Anglican chapel every morning and evening, to sing hymns in Latin on Sunday evenings and struggle through The Gospel According to Matthew in Greek. I acted as Joseph in the Christmas pageant, and one of the boys at my school is now Archbishop of Canterbury. Then, studying nothing but literature from the ages of seventeen to twenty-five, I immersed myself for eight years in Milton and Donne and Beowulf, before voyaging out into the depths of Melville and Emerson and Emily Dickinson.

But I think our deepest interests are formed by something more than circumstance. As someone who travels, I go to North Korea or Yemen to see how life is constructed very differently there, and so to wonder, "What is universal? What really sustains us?" Because I was lucky enough to enjoy an exhilarating job four blocks from Times Square in my twenties, I was moved to ask, "What is beyond this? And how can I find a life very far from the clamorous world to complement this?"

The wisest spirits I know seem always to refuse to be distracted by the symptoms and to go back to the source. If I'm worried, or fearful, or if the body-politic is confused, it makes no sense simply to tinker with the surface; one has to go to the root cause, the way a lesion on the skin often needs to be treated with surgery within. I've never been so interested in what kind of car I drive as in how the engine works.

Bridging, connecting, and juxtaposing East and West has been a central theme in your writing. What do you think are the chief misconceptions Westerners have of the sacred traditions and practices that originate in Asia?

Oh, I could write a book on that—and I probably have done, too often, already! But certainly, as someone who looks Indian and spends much of his life in California, I've seen how people ascribe to me certain kinds of wisdom or yogic power that, alas, have nothing to do with my life or my growing up in England. And as someone from the U.S. going off to seek wisdom in Kyoto at the age of twenty-nine, I found myself yet another Westerner looking for something on the far side of the world that I could surely find at home.

But I love your question, and if the blessing of my lifetime has been to see how many of us, increasingly, can learn from the wisdom of every tradition, its shadow side has been to witness how much can get lost in translation and how easily the calculating can take advantage of this. I'm always touched that the Dalai Lama refuses to be taken as a teacher, and asks only that people see him as a "spiritual friend." And I was struck at how, after witnessing close-up the exchange between East and West for many years, he began stressing more and more that people should not reach for traditions other than their own that perhaps they didn't fully understand or onto which they could project romances. It's impressive to me that one of the most visible religious figures of the age can always stress what is human, what is universal, and what stands up to empirical research and thus title a major book, Beyond Religion.

To generalize a little about your question, I think we in the West put into philosophical terms what is very practical, everyday wisdom in the cultures of China or Japan, say. Our notion of self is very different from the ones to be found in East Asia, which means our notion of self-dissolution or self-transcendence must be, too. And our sense of what a teacher is might be quite other than what you'd find in Shanghai or Kyoto; among my neighbors in Japan, I suspect, a Zen teacher is like a piano teacher, someone very accomplished in imparting certain skills, but highly fallible when it comes to other realms.

On the other side of the ledger, people in the East probably misunderstand what freedom is in the West, and the nature of abundance. Ever since my very first book, written 35 years ago, I've been fascinated, as you say, by the romances each side of the world projects upon the other, and the genuine human, universal beauties that sometimes result.

You once wrote, "If conviction is what separates us, as Peter Ustinov has said, doubt, at some level, is what brings us together." As the U.S. finds itself being torn apart by civil strife, can civil religion -- shared conviction -- still play a role in fostering social cohesion?

Goodness, I'd forgotten that sentence, and I've certainly always felt that those of us coming of age in the new millennium, living outside the old categories of black-and-white and East-and-West, even of high-and-low, are joined more by the questions we share than by the answers.

In terms of the extreme divisiveness we're witnessing in the U.S. right now, I've generally believed that we can only begin to heal and transform society by going within. In other words, I don't have much faith in collective solutions, in part because I feel that an individual is usually (though not always) more nuanced, more open, and more ready to cross party lines and surprise herself than a crowd. And I do believe that we begin to change the world by changing how we look at the world.

If we could all share agnosticism, a wish to listen, a readiness to assume we're not in the right, and an awareness that society can only be based on an appreciation of difference, I suspect we'd all be better off. I don't see that happening at the moment, and I do worry we're falling into a spiral of self-perpetuating demonizing of the other on both sides of the aisle. I wish others could follow me to North Korea to see the results of such provincialism and willed ignorance.

You've had the good fortune of spending significant time with Leonard Cohen, the Dalai Lama, and other spiritual luminaries. What are a few of the lessons you've learned from them about the spiritual life?

The most inspiring spirits I've met are, without exception, the humblest, the ones who never see themselves as better or different than the rest of us, the ones least inclined to think of themselves as teachers.

That is, the ones with the keenest sense of realism (and, therefore, the richest sense of humor and awareness of the frequent absurdity of life, or at least our thoughts of it). One of the joys of speaking so regularly with the Dalai Lama over 46 years is registering how little interest he has in airy-fairy affirmations, in easy answers, or in anything vaguely optimistic. As political leader of his people for more than sixty years, he knows that earnest, well-intended ideas get us nowhere in the very real world. The first things I see when I step into his hotel-room every morning at 8:30 are a copy of the day's newspaper, already well-digested, and a telescope pointing out the window to see how things are.

And of course, one of Leonard Cohen's great gifts was to search with such sincerity for clarity while turning such a droll and unillusioned eye on his very searching. He, too, had no interest in the namby-pamby or the unconsidered. He called his touring band at one point, "The Army," he wrote constantly of his own "panic" and "bewilderment"; he mocked the very fluency and charisma he possessed in such abundance. His constant theme, which is one reason he speaks to so many, is not that he's seen the light, but that he's struggling amidst the shadows.

Both of these wise men have been kind beyond measure, clear-sighted, unimpressed with themselves and exceptional company. But I always think of His Holiness as, first and foremost, a scientist and a scholar, only holding to what can stand up to empirical investigation. And I always recall Leonard as someone sitting outside the fads of the moment and looking for what could meet his Old Testament standards of justice and discipline.

Put differently, I suppose the beings I've most respected speak for the wisdom of Old Age, not the New Age, and hold to a tempered, humbled, exacting daily practicality that suggests an unswerving commitment to the real.

I might note that Annie Dillard is one of the great spiritual forces of our time, and she characteristically refers to herself as "a humorist."

You've written that many people, especially in the U.S., "seem to want religious light and fire, but without any of the institutional trappings." Much has been written about the decline of institutional religion in the West and the rise of self-made spirituality. Do you think the emerging DIY spirituality can have comparable power to morally orient lives and ground them in ideas and practices larger than the individual self?

Here again, you're reminding me of something I've forgotten I ever said. But it's true that I am more interested in those who say they're "religious, not spiritual"—as both the Dalai Lama and Leonard Cohen might—than the opposite.

For me, the transports of spirit—what we get from a moment in love, a Van Morrison flight, a glimpse of beauty, the cobalt heavens of Tibet—take care of themselves, more or less; we're all lucky to enjoy spots of time that carry us out of time and remind us of what's beyond us and, surely, inside us.

But what I associate with religion—self-sacrifice, community, devotion, obedience: that's the hard part! Thomas Merton gives us any number of radiant sentences about the soul alone with and in divinity; but the lesson he had to learn—which would be so difficult for someone like myself—is living in close quarters with dozens of other monks who, in other circumstances, he'd never choose to be with. And what moved me on meeting Leonard Cohen while he was living for five years as an ordained monk in a Zen community high in the chill mountains behind Los Angeles was that someone who had been such a questing spirit since youth was giving himself over to a really punishing discipline of scrubbing floors and shoveling snow and driving his teacher to the doctor, effectively erasing both "Leonard Cohen" and all his spiritual ambitions.

If I question "salad-bar" spirituality, it's, of course, because I am the main offender when it comes to such mix-and-matching. As someone growing up in many cultures in an ever more global world, I feel fortunate to have been exposed to so many different traditions and forms of wisdom; but the fact remains that I have never done the hard work of giving myself over to one for the long-haul, making a serious commitment and obliterating myself.

The Tibetans wisely note that it's far better to dig one well that's sixty-foot deep than ten wells that are six-foot deep each. And my sense is that a lifelong Hindu nun (even if American) or a Bishop Tutu can gain from and offer a lot to interfaith dialogue precisely because each of them has such deep roots in a tradition, hearing about other faiths can make them a better Hindu or Christian. But for someone like me, with much more shallow roots, it can lead to a kind of promiscuity—the DIY spirituality—that doesn't do justice to what is richest in any tradition.

What spiritual practices are important to you, personally?

Reading and writing are my main spiritual practices: Proust has taught me, as much as Buddhism might, about the power of the mind and its gift for projection and delusion; Rohinton Mistry or Elizabeth Strout have taught me about compassion and how to feel, to the point of tears, for either a stranger or the person who seems to have wronged you. After the one hour I try to devote to a serious work of non-fiction or novel every afternoon, I return to my not-so-real life appreciably more attentive, more intimate and nuanced, in a deeper part of myself.

And writing allows me to sit quietly for five hours every morning, trying to see what lies on the far side of my thoughts and to hear whatever voice there might be inside me or working through me that's wiser than I could ever be.

Beyond that, I try to go on retreat for at least three days every season: only 3% of my days, but it completely transforms and illuminates the other 97%. I've now made almost 100 retreats over the past 29 years in a Benedictine hermitage high above the California coastline.

And perhaps my main daily practice, trying to keep some of the clarity and peace of the monastery alive in my everyday existence, consists in all I don't do: I've never used a cell-phone, I try to avoid media, either social or mainstream, and I work hard to limit my time onscreen since the mediated world tends to cut me and my attention-span up, to leave me frazzled and disconnected and in a hurry. But when I simply look out or up, I'm generally opened out and feel moved, more spacious, much more hopeful.

Most of us have the choice, at every moment, of whether to turn our attention to what enlarges us or to what diminishes, and I want to make the most of that choice and to take no moment for granted.

Looking ahead 50 years into the future, where do you see the world in terms of spiritual growth or decline?

I think this COVID-19 season has really shown us all the folly of predictions; everything I've blithely said since March has been quickly proven false, and the uncertain movements of the virus have brought home how much, even in the calmest of circumstances, we can never say what's going to happen tomorrow, or tonight.

All the biggest moments of my life, good and bad, have come out of nowhere, entirely unexpected.

But insofar as movement across borders will surely continue, and keep accelerating, each of us will be ever more exposed to more and more traditions, even if we never leave our hometowns, and thus each of us will be faced with the challenges that brings, when it comes to discernment (and bewilderment).

I'm not sure humankind as a whole ever grows spiritually, which is one reason why I take my cues from Epictetus and Shakespeare and the Buddha and Jesus; I don't feel they knew any less than we do about how to live—or die. In many ways, they may, without the distractions of the "Information Age," have known more. Nor do I think we decline, or get any worse, even if the tools at our disposal for spreading grace or cruelty grow ever more powerful.

I only hope that, as we try to face the overwhelming challenge of climate change—and the refugee crisis, the widening gap between the haves and the have-nots, the need to understand the Other—we can look away from our screens long enough to see what really stands the test of time and turn to the wise beings we still have all around us, whether their names are Emily Dickinson or Etty Hillesum.

It's the fact that we don't know whether we'll be alive next week that should move us to try to live well right now. Rather than waste time speculating on the unknowable future, I want to make best use of the only given in my life—the great gift of the present moment.

10/29/2020 1:55:36 PM