In the noble pantheon of Irish saints, the main trio can be roughly compared to the heroes in the Harry Potter franchise. There's Patrick (Harry), Brigid (Hermione) and Columba (Ron). Just like his ginger-haired counterpart in this belaboured introduction, St. Columba seems a little underappreciated in Christian circles.

While both St. Brigid’s and St. Patrick’s feasts are steeped in tradition, St. Columba’s Day passes almost unremarked every June. There is more hype on World Statistics Day than on St. Columba’s Day. For someone who contributed so much to Celtic and Irish Christianity, that seems a raw deal. So, then, put away the green Paddy’s Day hat for a minute as we look at a lesser-known saint.

Adomnán’s Life of Columba

Hagiographies (mythicised biographies) of Irish saints are mementos of a more innocent period in this island’s history, penned a millennium before centuries-long conflict erupted in earnest. How far we fell, Adam-and-Eve-style, from supernatural tall tales – fabulous yarns by the likes of Adomnán – to the Troubles era, with its daily horror stories. Maybe that innocence can still be regained…

I digress. Let’s take a glance at Adomnán’s more… uh… creative claims about St. Columba. Here, I’m using the 1995 Penguin Classics edition translated by Richard Sharpe. The first anecdote is from Book One of Adomnán’s Life (§19). It centres on a monk in Columba’s Iona monastery with a sea voyage to make. Before the brother departs, though, the Saint admonishes him to take an indirect route across the water. This is to dodge a terrible monster, which lurks in the deep.

Unsurprisingly, the man jettisons Columba’s cryptic advice immediately. The vessel’s unfortunate crew happen upon the monster, as predicted: ‘a whale of extraordinary size, which rose up like a mountain above the water, its jaws open to show an array of teeth.’ Yikes!

When hagiographies mention so-called monsters, it’s fun to guess which creatures they were in fact. After all, Sixth Century monks couldn’t refer the matter to David Attenborough. Whales don’t have teeth in the conventional sense – well, the whale from Finding Nemo didn’t. Its dental gear was like prairie grass – which makes Columba’s monster a shark, in all probability.

‘Remembering what the saint had foretold,’ relates Adomnán, ‘they were filled with awe.’ No surprises there. I would be filled with awe too! Thankfully, the foolish oarsmen make it safely back to shore after their ordeal, no doubt resolved never to disobey their clairvoyant abbot again.

In Book Two (§16), there is a narrative where Columba conducts an exorcism on a boy’s milk bucket, like some televangelist who took a wrong turn and ended up on a cattle ranch. (Yes, this is a real thing Adomnán wrote!) ‘Saint Columba did not come near but raised his hand and made the saving sign of the cross in the air in the direction of the pail,’ so the story goes.

One does have to wonder whether haunted milk was a widespread problem in Ireland when Columba ministered, or whether this was just a one-off occurrence? At any rate, it isn’t an issue which often besets us here today. Thanks to pasteurisation, demon-free dairy produce is now sold and enjoyed island-wide.

And so, Columba signs a blessing over the bucket, ‘which at once shook violently,’ whereupon the milk all slops to the ground. This, however, is no bother for our Sixth Century Damien Karras, who miraculously refills the bucket ex nihilo. Columba said, “Let there be milk,” and there was milk!

He chides the boy for his failure to check the milk-pail for evil spirits before he milked the cows – I know… how careless can you get? – before he sends him on his way with a full pail. To this day, farmers are still required, both in statute and EU regulation, to make sure no fallen angels end up in their products. It all stems back to this anecdote.

Another one for the road. Slightly later in Book Two (§29), a monk approaches the saint while the latter is deep in concentration at his desk. The brother’s request is that Columba bless his knife. Absorbed in his work, the holy man absentmindedly signs a cross over his charge’s knife.

An hour afterwards, the monk draws his newly blessed blade to use it on a young bull. He thrusts the weapon three times. Each time he fails, inexplicably, to pierce the bullock’s hide. Apparently, Columba has invoked the spirit of Gandhi on the knife, making it henceforth incapable of any harm to living things.

There are monks in Columba’s abbey who know how to smith metal. These fine gentlemen seize the knife to melt it down, sensing a use for it. Saintly blessings remain within the metal even as it changes from a solid into the liquid state, you know – something we should’ve covered in high school science.

Anyway, the blacksmith-monks coat all their other tools in gloopy knife-metal. These implements, like the original knife, become unable to stab anything. I do wonder how they verified this. Did that bull calf just have to stand there like a four-legged scarecrow, bored out of its mind as monks thrusted one tool after another at it? Who knows!

Well, folks. There is a sample of Adomnán’s yarns for your amusement, postcards from a gentler time in Ireland’s history. But our adventures with Columba cannot stop here. Fun though they be, hagiographies by colourful raconteurs are limited in their ability to get across what happened in the past. Our quest for the real Columba will have to go beyond the pages of legend.

Following in his footsteps

To get even better acquainted with Columba, your blogger here went up to Derry, which is Ireland’s fifth largest and most northerly city. This is where the man conducted part of his ministry. References to the Saint abound in this historic settlement. Upon arrival, then, I stopped at an eponymous chapel – St. Columba’s Church, Long Tower – where eucharistic adoration was in progress.

By the way, St. Columba’s Church is home to Derry’s friendliest cat: a lively tortoiseshell, perhaps the man himself returned in feline form to guard the modern-day faithful. His little routine, performed roughly half a dozen times, involved mid-sprint ninja-leaps at my shins, which nearly sent me flying. This was followed, upon landing, by squirmy puppy-like rolls on his back. Rather adorable.

The building’s portico bore the motto: Vere, non est hic aliud nisi domus dei et porta cœli. This means: Truly, here is none other than the house of God and the gate of heaven. That, in brief, is Catholic ecclesiology. Beneath is a semi-circular stained-glass window. This depiction features Columba dead centre. The Saint appears, as four other characters look on, to be levitating… or walking on water… you decide!

Moving clockwise away from the portico, there is a courtyard where a sacred stone lies under a metal canopy. The stone is embedded within a large pedestal on which a Calvary scene is constructed. A Columba figure has his left hand placed on the special stone to mark it out. In his other hand, raised aloft, is a miniature cross. To the pedestal is affixed a gold-lettered plaque, which explains the saintly rock’s history: ‘Venerated from time immemorial in Derry, because of its traditionary association with St. Columba…’

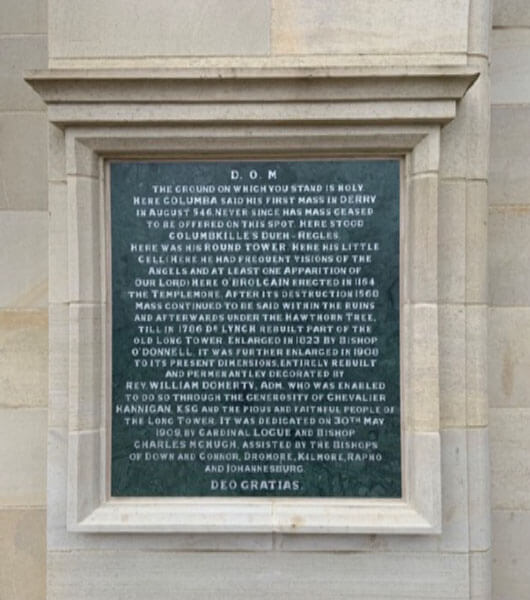

To the left again is an entrance to the chapel, on which is mounted another plaque. It refers to the site as a whole: ‘The ground on which you stand is holy. Here Columba said his first Mass in Derry in August 546.’ As I walked around St. Columba’s Church, passing plentiful gravestones in the style of Celtic high crosses, this place did indeed feel hallowed.

Ireland is for life, not just for St. Paddy’s Day!

Crawford Gribben, in The Rise and Fall of Christian Ireland (2021), sketches the rivalries which sprang up among Ireland’s monastic federations, who devoted themselves to different Irish saints. This island’s history, God knows, is riven with strife between Christian factions. ‘These federations published waves of propaganda, of which hagiography (biographies of saints, often with fantastic content) was a central part,’ Gribben explains (p. 39).

Each would compose with a view to shoring up their favoured saint’s reputation, ‘to defend their claims to primacy, so that Iona’s promotion of Columba competed with Kildare’s promotion of Brigid and the promotion of Patrick at Armagh’ (ibid.). Suddenly, the rationale behind all those fanciful tales in Adomnán’s Life of Columba starts to make sense!

But Gribben’s analysis points to something else: the difficulty with trying to learn about one Irish saint without reference to the rest. When we single Patrick out as if he were Ireland’s only saint, we might overlook his influence on his followers – who bequeathed, in turn, their own legacy. Before Columba there was Brigid. Before Brigid there was Patrick. Celebrate Patrick’s ministry with a cheeky Guinness, of course, but remember Columba while you’re at it. Sláinte!

Happy St. Patrick’s Day from Ireland.

3/17/2023 4:55:02 AM