For me, Jimmy Carter’s death came too soon.

Not necessarily because of his age. He lived to the ripe old age of 100 and, in many respects, lived those years to the fullest.

No, and if I may be crass for a moment, Carter passed before I had a reporting guide ready for reporters looking to cover the faith angles of his life and legacy.

You see, as Editor for ReligionLink, I put together resources and reporting guides for journalists covering topics in religion. Each month, we publish a guide covering topics such as education and church-state-separation under Trump, faith and immigration or crime and houses of worship.

Early in 2024, I started to put together a guide to cover the passing of Jimmy Carter. Serving as Editor is only a part-time gig, and it usually takes all the time I have dedicated to the role to produce a single, monthly guide. But on the side, I started to make notes, identify sources and build a timeline for Carter’s life and legacy.

When he passed on December 29, 2024, the guide was not ready. Nor would it be in the matter of days necessary for it to be useful. So, the opportunity came and went. The draft of the guide to covering Jimmy Carter’s passing tossed on the editing floor.

The missed occasion, however, inspired me to work ahead more intentionally on guides for other famous faith leaders. The process of putting such guides together led me to reflect on what it means to remember, and report on, the passing of prominent figures in religion.

On The Passing Of Prominent Figures In Religion

Writing an obit is a craft.

Good obituaries not only cover the who, what, when, where, why and how of a person’s life, but something of their personality and what made their lives extraordinary. The best obituaries go beyond the formula and capture something of the individual’s spirit and the why behind their impact and life well-lived. Even if a person’s life was not particularly notable, I believe there is something ordinarilyextraordinary in everyone’s biography. The little details of our lives add up to something memorable, important and perhaps insightful. The job of the obit writer is to capture that in the text of the necrologue.

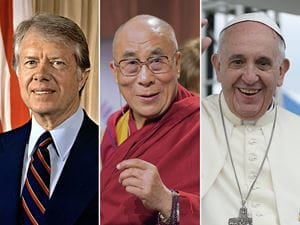

And in the case of significant figures like a pope, dalai lama or the Aga Khan — or leaders like Jimmy Carter or Archbishop Desmond Tutu — obituaries can also serve as potent reminders of the critical role religion continues to play in politics, economics and global affairs. Despite the waning influence of institutional religious adherence in the Global North, such figures, and their faiths, shaped major moments in the 20th and 21st-century histories.

Not Only What Happened, But What’s Ahead

An obituary, remembrance or other piece on the passing of an important figure is thus more than a look back on a life and legacy; it is a look forward to what that legacy will mean in the years ahead and how that life will impact individuals, communities and institutions in the future.

For example, as I worked on the guides to cover the passing of Pope Francis, who is 88 years of age and the 14th Dalai Lama, 89, I was struck less by the details of their biographies and careers — though they are significant and feature prominently in the guides — and more on what comes after.

Because in both cases, there’s plenty of uncertainty.

In an interview with the Spanish daily newspaper La Vanguardia in June 2014, Pope Francis was asked how he would like to be remembered. He famously replied, “‘He was a good guy, he did what he could, he was not so bad.' I would be happy with that."

Self-deprecating replies aside, Pope Francis’ legacy will be one of both subtle, progressive changes in the church and sometimes acrimonious ideological divides. Since becoming pope in 2013, Francis has pushed to make the church more inclusive and welcoming to women, LGBTQ+ people, people of other faiths, migrants and Indigenous peoples. He also took firmer stances on such issues as climate change, the death penalty and nuclear power. He has also embroiled himself in controversies over sexual abuse in the church, the celebration of the Latin Mass, and church governance.

Conservatives have decried what they see as a leftward lurch away from centuries of tradition — some cardinals going so far as to express theological doubts (dubia) about Francis’ positions — while more progressive voices within the church protest that his reforms did not go far enough.

Altogether, it seems likely that Francis will leave a church more divided than it was at the beginning of his pontificate and that the process to select his successor will be highly politicized.

At the same time, Pope Francis has been a shrewd political maneuverer. Wanting to cement his legacy and desiring the church to continue his reforms, Francis has appointed bishops, created cardinals and favored allies for key positions, which may cement his reforms and would be difficult to replace or remove by a future pope opposed to Francis' preferences. As a result, the College of Cardinals is younger on average than when Francis was elected, and new archbishops in Brussels, Buenos Aires and Madrid likely have somewhere around two decades ahead of them.

The impact of these changes, and the question of Pope Francis’ legacy, will first be asked at the impending conclave that will come in the days following his death.

The Dalai Lama Dilemma

And in the case of the Dalai Lama, the ramifications of potential succession are perhaps even more dramatic.

As a "Living Buddha," the dalai lama is always expected to reincarnate. But the question of the 14th Dalai Lama's successor remains unsettled.

Looming behind the uncertainty is the People’s Republic of China. Having ruled Tibet since 1950, PRC authorities claim they have legal jurisdiction over the process and the authority to approve the candidate — citing a 1793 imperial ordinance that was used in the cases of the 11th and 12th dalai lamas. Moreover, Beijing has already said the dalai lama will reincarnate in China.

However, the current Dalai Lama promised to consult leading lamas — venerable spiritual guides — and the Tibetan public to decide near his 90th birthday (on July 6, 2025) whether the institution would continue after him.

The Dalai Lama has hinted that he might that he might not reincarnate, potentially ending a role that has been key to Tibetan Buddhism for more than 600 years. He has also suggested he might reincarnate outside Tibet — in other words, in what he termed the "free world" outside the PRC — or be a woman. Regardless, he has warned that no other reincarnation should be recognized apart from the process undertaken by Tibetan leadership.

Nonetheless, if the dalai lama reincarnates outside the PRC, experts suggest Beijing will almost certainly move to pick a new dalai lama within China's territory.

Religion Remains Important

Altogether, these impending passings — and the paths that the respective, impacted institutions and governments take in the aftermath — serve as another potent reminder of religion’s resilient relevance in a supposedly secular century.

Regardless of our personal faith (or lack thereof), religion remains a powerful force that influences governance, shapes global affairs and structures the lives we lead – and perhaps the deaths we will one day have.

Thus, as I was prompted when I was caught out by Carter’s death in December, it would do us well to be prepared for prominent religious figures’ passing and pay attention to what comes next.

4/1/2025 3:32:54 AM