By Kara Bettis

The following is an exclusive feature that has been shared with you but is otherwise available only in Volume 2, Issue #1 of the Christ and Pop Culture Magazine.

For more features like this, download our app for iPad and iPhone from Apple’s App Store.

After a one-week free trial, monthly and yearly subscriptions are available for $2.99 and $29.99 respectively. New issues are made available every other week. More information here.

We millennials who grew up in a traditional evangelical home had to fight a delicate battle to gain cultural literacy. We had to secretly watch Disney movies in college to keep up with Lion King jokes, and confess that Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ stole our R-rated movie virginity. In our college years and beyond we find that we may have overreacted, either accepting all media as necessary cultural immersion, or making little connection between self-control and media consumption. But if we are to engage the world, isn’t a balanced and informed appreciation of culture necessary?

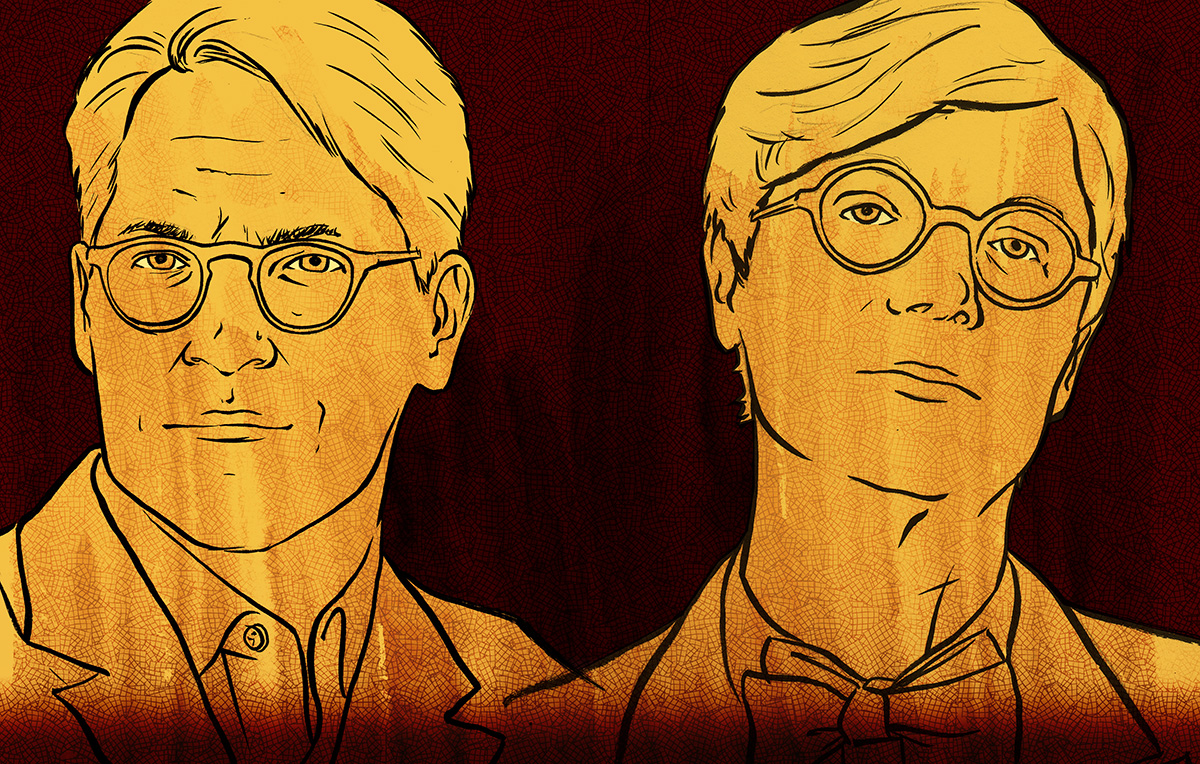

Two of the most influential evangelical Christians in New York City swim daily in contemporary cultural texts. Eric Metaxas, author of the New York Times #1 Best-Seller Bonhoeffer and founder of Socrates in the City is close friends with Dr. Gregory Alan Thornbury, the new president of The King’s College. While the two evangelicals share a similar values, their backgrounds are surprisingly different. Thornbury comes from a conservative, evangelical home while Metaxas tells of a dramatic conversion while attending Yale University.

Both men observe the need to “know thyself” in making wise personal entertainment choices. When the individual understands themselves, they can avoid making ridiculous judgments and instead develop temperance. As John Calvin writes in the Institutes of the Christian Religion: “Nearly all wisdom we possess, that is to say, true and sound wisdom, consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves.”

Although fluent in most forms of cultural criticism, Thornbury especially loves music. One of his models is Larry Norman, the father of Christian rock and roll who integrated messages about sex, drugs and Jesus. “He helped us think through these issues 40 years ago,” Thornbury says. “He was fearless about talking about Jesus but loved pop culture.”

Raised in a conservative Christian home, Thornbury remembers his mom’s fear when he snuck home Bob Dylan and U2 records. When Thornbury listened to The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band he found it liberating. “I remember thinking, ‘the church doesn’t have anything like this,’” he says.

What’s changed in the past few generations? If knee-jerk legalism is of the past, Thornbury pushes further to say that the church’s real difficulty with the entertainment industry lies in discipleship. Like alcohol, there are no clear biblical imperatives about entertainment. And yet, readers of Scripture still know that it can be counterproductive to discipleship.

“We have not given a hermeneutical grid on it in the church–the things that you might discipline yourself to listen to [or] not to watch. There are so many sermons about the dangers of legalism. I don’t think that’s a danger today as much as a lack of desire for holiness,” Thornbury says.

Both Thornbury and Metaxas share concern over the lack of restraint shown by most Christian consumers of media today. Metaxas fears that the dramatic reaction of swinging away from fundamental, puritanical tendencies in the meantime desensitizes people to real evil. Even further, Metaxas fears that the consumers in our culture might lose a kind of innocence. “Can you do something to your mind? I worry for these young people and what they are exposing themselves to. Sometimes we see things that never leave us and are genuinely harmful,” Metaxas says.

Metaxas has written in Books and Culture about his disillusionment with Martin Scorsese’s bloodlust, which forced violent scenes in “Gangs of New York” and “Casino” on a naive American public. Metaxas certainly does not shy away from engaging the entertainment industry, but exercises constraint in his personal life. Although violence in films did not bother him in his younger years, Metaxas says he regrets two mistakes in his film consumption: he found the evil he encountered in Pulp Fiction and The Exorcist disturbing as a man of deep faith.

Our entertainment choices are not merely an individual issue: we need to learn to be unselfish. Metaxas says that he may choose to view a movie but wouldn’t encourage his friend to do likewise if he thought it would be harmful.

Metaxas cuts to the point. “Your generation is not aware of the weaker brother,” he says. “Are we all about furnishing our own image of hipness or are we caring about the souls of others? It’s just worldliness.”

Even with Metaxas’ personal restraints and Thornbury’s freedom within discipleship, both are extremely fluent in cultural artifacts and influential among New York City’s culture creators.

Metaxas believes that this generation of creators have become immature in dealing with darkness as they shove it in others’ faces. Showing the bloody corpse or the explicit sex scene can be a copout for the artist since he no longer must operate creatively to narrate sexuality or the evils of violence. Metaxas personally enjoys John Ford’s westerns and similar classics as they face truly dark themes without copping out creatively in explicit demonstrations of evil.

Thornbury says that he curates sources he finds to be “spiritually awake”–for example, he tends to be edified more by the sinful choices of Don Draper in Mad Men than sermons on sanctification.

Even the apostle Paul read and memorized his cultural texts like the Cretan poets in order to engage his listeners. “If it’s good enough for the apostle Paul, it’s good enough for you,” says Thornbury.

Thornbury believes in the importance of reading cultural texts in their religious contexts: “At the end of the day, what [people are] doing is precisely what Paul is saying—groping towards God [Acts 17]. If that’s true, then God is only one or two steps away from any conversation. I think that gives me warrant to go expeditioning into the arts, into poetry: because it’s going to ultimately take me there.”

Kara Bettis is a recent graduate of The King’s College in New York City, where she studied Media, Culture and the Arts. She has written for World on Campus and World Magazine. Check out @whatakaracter or Heartbeats.

Illustration courtesy of Seth T. Hahne. Check out Seth’s graphic novel and comic review site, Good Ok Bad.