By D.L. Mayfield. The following is an exclusive feature that has been shared with you but is otherwise available only in Issue #10 of the

Christ and Pop Culture Magazine. For more features like this, download our app for iPad and iPhone from Apple’s App Store.

After a one-week free trial, monthly and yearly subscriptions are available for $2.99 and $29.99 respectively. New issues are made available every other week. More information here.

D.L. Mayfield

I went to a show the other night, bought the tickets online, made all the necessary arrangements for a babysitter, tidied up my apartment, put the toddler to bed and put on a clean pair of pants. My husband and I got on our bikes and pedaled the 1.5 miles to downtown where we showed the doorman our ID’s and received age-appropriate wristbands. Inside, it was cool and dark and people our age and older milled about, drinking tall boys and laughing. We all eyed each other somewhat warily: this was a reunion of sorts, and it was necessary to size each other up. I surveyed the room, and felt my heart sink a little.

We were all there to see the reunion tour of Five Iron Frenzy. The last time I saw them was 14 years ago, when my hair was cut short, bleached blonde, and they performed at a roller rink (The Holy Rollers tour, they called it). I remember being 15, dancing my cares away, surrounded by freaks just like me. We were the uncool kids, finding solidarity in the sweaty mess of the mosh pit, our allegiance to a little-known but well-beloved band of intelligent fools, we were the ones who getting kicked in the teeth for being who we were: kids born into a Christian world, forced to live in a secular one. This band made it ok for us to dance, to scream, to doubt, and ultimately, to believe it all. There was a God who loved us, after all. Just like he loved everyone else.

But now, at the reunion concert, there are precious few freaks. We have, as a whole, aged well into our bodies. People are comfortable, subdued, wearing tasteful v-necks, Warby Parker glasses and pants that fit well.

We have grown up, it would appear. So why are we all here at the show?

//

Five Iron Frenzy is one of the few: an Evangelical Ska band with a staying presence. Eight albums, an EP, and a host of singles make up their discography from 1996-2003. They toured continuously in those years, playing both the big Christian festivals and small-town bars, straddling the line between youth group events and secular tours like Ska Against Racism. Composed of 8 band members, Five Iron Frenzy at first seemed like a one hit wonder: chaotic music, manic vocals, playing to crowds of young teenagers. But something stuck, and a formidable fan base was created. Although, until this past year, perhaps no one realized quite how strong the bonds between fans and band were.

Five Iron Frenzy is one of the few: an Evangelical Ska band with a staying presence. Eight albums, an EP, and a host of singles make up their discography from 1996-2003. They toured continuously in those years, playing both the big Christian festivals and small-town bars, straddling the line between youth group events and secular tours like Ska Against Racism. Composed of 8 band members, Five Iron Frenzy at first seemed like a one hit wonder: chaotic music, manic vocals, playing to crowds of young teenagers. But something stuck, and a formidable fan base was created. Although, until this past year, perhaps no one realized quite how strong the bonds between fans and band were.

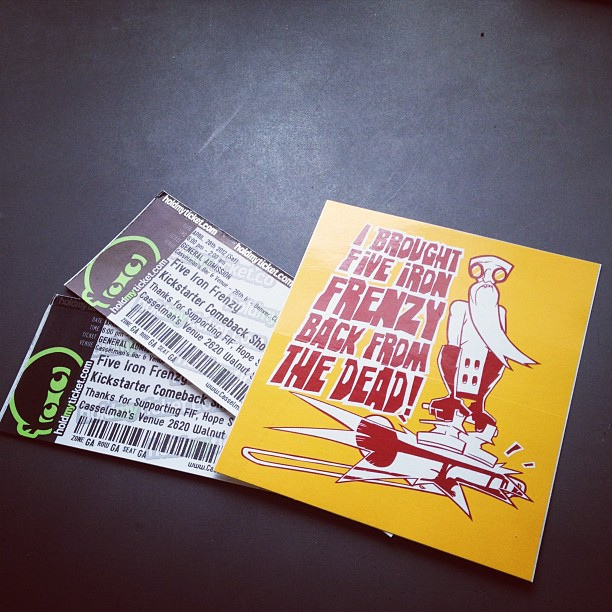

In May of 2012, the band launched a Kickstarter project to fund a new album, asking for $30,000. The goal was met in record time (less than an hour), and the band went on to make Kickstarter history (they are still in the top-ten most funded musical projects—with over $200,000 raised in six weeks). By all accounts, the band was as surprised as anyone by the outpouring of love (and money) that met their news of more music.

So they decided to tour. Nostalgia, it would seem, is a very powerful force.

//

I stared at all my fellow Five Iron fans, all of us a decade older and wiser since the band had officially called it quits. I had a notebook in my back pocket and I wrote down things like: bud light with lime. Hipsters. Only one guy with a strange aviator hat on. The opening band was playing loud, poppy punk. Ten years ago I would have thought the lead singer was a knockout. Now, I just stood with my arms folded and thought: how does he swivel around in those tight pants? Is this what he does for a living? He seems a bit too old for all this, really. And then, in between songs, he did something that I have not heard for quite awhile: he gave a punk rock altar call. “Rock n Roll is great,” he said, breathing heavily into the mic, “but it doesn’t compare to the most important thing in life.” The crowd got quiet, people turning to look at the stage with rather blank expressions, drinks in hand. “And that decision is whether or not you are going to make Jesus Christ the Lord of your life.” He talked a bit more at length about that decision, then played one last sweaty song with his band. As far as I could tell, the crowd was non-plussed. Maybe they, like me, were having flashbacks to our own youth. One where we were constantly being asked to rededicate ourselves, even as the definition of what that meant got harder and harder to quantify.

I asked several people why there were here, at the reunion show. Two people told me that FIF literally saved their life. What does that mean, I asked, trying not to sound skeptical. It was one thing to hear a statement like that from a 14-year-old, and quite another to hear it from people staring down middle age. “I dunno,” one girl said, her bangs cut short and straight across her forehead. “They made it ok to not be cool and to know that no matter what, Jesus would still love you.” I heard the same sentiment from several others milling about. Although many of us now looked like normal adults, one common factor seemed to be hellish recollections of adolescence. Songs like “Suckerpunch” spoke directly to this: “They’re all sucker-punching me/get in line for a wedgie/all I want and all I need/is someone who believes in me.” I remember screaming out those lyrics myself, knowing deep in my heart that God did believe in me. And in my teenage haze, I also believed that Five Iron Frenzy believed in me too. It was a great comfort to me at the time, and evidently I wasn’t alone.

//

After the Evangelistc punk rockers left the stage, the crowd is ready and waiting for Five Iron. The band comes on stage, all 8 of them, looking vaguely like I remember (give or take a decade). The two people I always cared about the most are still recognizable, anyway. First, there is Reese Roper, the lead singer/main lyricist for the group, who refused to sign autographs at his shows and thus sealed in my heart an adolescent adoration, him being the epitome of non-conformity. Later, as I grew up, I was pleased to hear that Roper eventually left the music industry to become a scientist, working in a lab. This picture of him, nerd glasses and a lab coat on, seemed so appropriate, seemed so in line with the ethos of the band: have fun, don’t sell out, quit when you are ahead. In the Christian music scene of the late 90s-early 2000s, this was a rare sign. Most bands broke up due to infighting, shattering their teenage fan’s loyalty (one man told me he had to take a step back from music altogether, due to so many of his favorite Christian bands breaking up). Others did not go gently into that good night, playing for smaller and smaller crowds, until people finally gave up, cut their hair, and got “real” jobs. I thought of Reese and his band as people who bucked the trend. They quit before they could go sour right before our eyes—which, I am only now realizing, assured a dedicated and excited fan base for when they came back. Reese Roper the man is recognizable in his frontman role, but different too: close cut hair, tight t-shirt, beefy arms. If I didn’t know any better, I would say he looks like the opposite on an outcast. He very much looks like someone who is trying to fit in.

After the Evangelistc punk rockers left the stage, the crowd is ready and waiting for Five Iron. The band comes on stage, all 8 of them, looking vaguely like I remember (give or take a decade). The two people I always cared about the most are still recognizable, anyway. First, there is Reese Roper, the lead singer/main lyricist for the group, who refused to sign autographs at his shows and thus sealed in my heart an adolescent adoration, him being the epitome of non-conformity. Later, as I grew up, I was pleased to hear that Roper eventually left the music industry to become a scientist, working in a lab. This picture of him, nerd glasses and a lab coat on, seemed so appropriate, seemed so in line with the ethos of the band: have fun, don’t sell out, quit when you are ahead. In the Christian music scene of the late 90s-early 2000s, this was a rare sign. Most bands broke up due to infighting, shattering their teenage fan’s loyalty (one man told me he had to take a step back from music altogether, due to so many of his favorite Christian bands breaking up). Others did not go gently into that good night, playing for smaller and smaller crowds, until people finally gave up, cut their hair, and got “real” jobs. I thought of Reese and his band as people who bucked the trend. They quit before they could go sour right before our eyes—which, I am only now realizing, assured a dedicated and excited fan base for when they came back. Reese Roper the man is recognizable in his frontman role, but different too: close cut hair, tight t-shirt, beefy arms. If I didn’t know any better, I would say he looks like the opposite on an outcast. He very much looks like someone who is trying to fit in.

The other person in the group my eyes are drawn to is Leanor Ortega, better known as “Jeff the girl”. Leanor, the sax player of the group, looks the same to me: the only forlorn girl in a sea of testosterone. I have done a bit of research before the show and know that Ortega is now an ordained minister, a missions pastor at The Scum of the Earth church in Denver, married with kids. She looks like me: hair slightly frizzy, clothed for comfort and performance, nothing spectacular. Except that she is a groundbreaker, I realize that now.

When I was a kid in the crowds (the first time I saw FIF was when I was 12), I only had eyes for Leanor. In a world so small and full of non-conformity in the most unanimous of ways, a girl playing an instrument in an alternative Christian band was rare. She played well, held her own in all the banter, piled into the van with the guys and went to the next tour stop along the way. And the entire time she was friendly, approachable, good at her instrument and never belabored her gender (well, her nickname maybe did that for her). After I saw FIF play for the first time, I went home and taught myself how to play bass guitar. Then I rounded up a few family members and friends and started a Christian punk band. We toured Northern California for a year or two, playing at youth groups and Christian clubs; we were interviewed by the local paper (my most famous quote: “Christians can be punks, too.”). I was thirteen years old.

I remember all of this in the minutes that the band takes to set up and launch into their first song, the deceptively silly “Blue Comb ‘78”, a song I always thought was just about Reese Roper and his little sister getting into a fight in the car, ending with her throwing his favorite blue comb out the window. Now, all of us almost-middle-aged folks singing our guts out, and I finally understand what the song is really about: nostalgia. About being a kid, sweaty summer vacations in cars with no A/C, back when you and your sister were best friends, when your parents still loved each other, when you knew exactly how much space you took up in the world and it was good. We were singing a song about nostalgia at a concert that was created by nostalgia. All of us were there, in one way or another, to recreate what it had felt like to be at a FIF show a decade or more ago. We were trying to remember those times of teenage angst, which seemed so bad to us at the time but in their own way hold the subtle gentle sway of memory. Life wasn’t really that bad, back then. At least we still believed.

//

It seems hard to imagine, but when I was growing up, an artist who straddled the (admittedly artificial) Christian/secular divide like Sufjan Stevens was still just a pipe dream. Growing up as a pastor’s kid in America, my musical choices were few and far between. There were the megabands like DC Talk and Audio Adrenaline, and all the praise music my mom listened to. And then one day, I heard MxPx on a mixtape and my life was changed, forever.

It seems hard to imagine, but when I was growing up, an artist who straddled the (admittedly artificial) Christian/secular divide like Sufjan Stevens was still just a pipe dream. Growing up as a pastor’s kid in America, my musical choices were few and far between. There were the megabands like DC Talk and Audio Adrenaline, and all the praise music my mom listened to. And then one day, I heard MxPx on a mixtape and my life was changed, forever.

Thanks to labels like Tooth and Nail, the Christian alternative scene exploded not only into my consciousness, but into youth groups everywhere. For a few golden years, Christian kids had it all: their own scene, their own devoted bands, all at an affordable, indie-label price. There were safe, and encouraged, places where kids could dance, scream, and shout—all without the influence of drugs or alcohol. It was the sweet years before the marketers caught on, before bands were groomed to be both blandly theological and meticulously coiffed, before bands like Skillet could charge $40 a night, before Christian youth became seen as big-fat-spending-cash machines. There were a few years of honest-to-goodness ingenuity, passion, and creativity, marked by bands like FIF, who had legitimate crossover appeal because they were unique: good music, interesting lyrics, killer stage presence. But those years have ended, and the current scene for Christian youth is largely controlled by a few larger labels, increasingly generic rock bands, lyrics that shy far, far away from any sort of controversy. A new day has dawned in Christian music. Let’s take a moment of silence for the golden years, the ones that a few of us had the privilege of living through.

But maybe that isn’t true. Isn’t that the way of nostalgia? To convince everyone that you were the special one, had the hardest adolescence, listened to the coolest bands, had the most penultimate concert experience where Reese Roper sang that one song about Native Americans and you just really got the whole manifest-destiny-white-privilege thing. But really, a thousands times over, kids almost just like yourself were having that same experience, give or take a few horrors or epiphanies. And it happened the next year, with a new band, a new crowd a new scene. And the next year, and the next year, and the next.

Nostalgia is kind only to the past. It troubles the present, those few times we are asked to face up to our own romanticized idealizations of our youths and see them for what they really were: universals, not individuals. All teenagers feel like losers. All people of faith must start grappling with doubt. All bands, no matter how good or great they were, must break up. Some people never get comfortable in their own skin. Many will walk away from the faith they had as children. And some bands, for reasons more mercenary than artistic, get back together again.

But nothing is ever the same.

//

The music is loud, yet tight. FIF the band obviously enjoys being on stage, living out their own sort of reunion. Their in-between-songs-banter is rambling, incoherent, and very funny. Somebody yells out “shut up and play something!” Roper puts his hand over his eyes and looks into the crowd. “Heckler!” he says, like he has found a long-lost friend. “Oh, we have missed you!” The crowd laughs. He goes on: “Nobody ever heckles us in our regular jobs!”

The music is loud, yet tight. FIF the band obviously enjoys being on stage, living out their own sort of reunion. Their in-between-songs-banter is rambling, incoherent, and very funny. Somebody yells out “shut up and play something!” Roper puts his hand over his eyes and looks into the crowd. “Heckler!” he says, like he has found a long-lost friend. “Oh, we have missed you!” The crowd laughs. He goes on: “Nobody ever heckles us in our regular jobs!”

They play some more music. Some new, with a bit more of a grand, theatrical air about it. They mention their new album coming out this fall many, many times. There is a mosh pit forming in the front of the crowd, the nicest crush of people you would ever meet. People sing along to the lines, and I envision them as their younger selves, their very identities being tightened and refined by these lyrics. Songs about sin and sinners, materialism and nationalism, about grace and redemption, songs about choosing to believe in it all anyways, in spite of everything.

I make my way through the sweaty crowd to the very back, in the amber glow of the lights next to the bar. I am too tired to stand, astonished at how much energy it takes to dance the way I used to. I don’t remember all the words to the songs anymore, anyways. My own life has been forged by much more, and the lyrics that once changed me now seem to barely scratch the surface of a world so beautiful and terrible that I simply cannot comprehend it.

Reese looks out on the crowd, near the end of the set. He looks happy, energized, and older. “It’s not a school night,” he says into the mic, “so we can go as late as we want!” Inwardly, I groan. A two-year-old sleeps in for no one, this much is true. Leanor steps up to the mic herself “But people have kids,” she says, as Reese continues to look at the crowd. “What?” he asks her, as the crowd looks on. “We all have kids now,” she says, gesturing to the crowd. “People have to go home and pay the babysitter.” We all laugh, as the band plays their last song, because it’s true.

We’ve grown up. We all have kids now and countless untold responsibilities crowding our minds. But for one night, for a mere $20, we got to pretend that we were right back where we started: a part of something bigger and better than just our own little lives. The music sounded the same, all right, but our ears were different.

And no matter how hard you try, you can’t recapture the past.

D.L. Mayfield’s life is about 90% mundane and 10% cray-cray. She loves food and books and a good outsider perspective portrayed in pop culture. She gets very, very excitable when anyone mentions the phrases “kingdom of God”. You can find her blog here and on twitter as @d_l_mayfield.

Image credit: lancefisher via Flickr (CC-BY-SA 2.0)