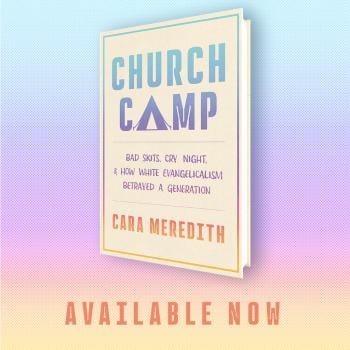

This is a sermon from July 31, 2022, given at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Oakland, California. Enjoy!

—

My parents were in town this last week, visiting from Oregon. And on Thursday, as we were sitting down to lunch, my mom said, “Do you know where Mountain View Cemetery is?”

Mountain View Cemetery? I thought, thinking about the likely town of Mountain View, over on the Peninsula.

“Nope,” I finally responded. I chewed my turkey sandwich.

“Well, it’s here in Oakland,” she said. “My father was buried there. I haven’t been to visit his grave since I was twenty, and I thought perhaps we could see if we could find the tombstone.”

My grandfather was buried here? This I did not know.

Her father, who had rheumatic fever and scarlet fever as a child, died after a series of strokes when she was two months shy of her sixth birthday. Now, at seventy-six, it had been nearly sixty years since she’d visited his grave. YES, we’d pay the cemetery a visit, for yes, this cemetery, as many of you well know, is here in Oakland, just off Piedmont Avenue.

A few minutes later, we were on our way. We knew the section. We had the plot number. We would find his stone.

Soon enough, with map in our hands, we drove up the hill – past the first fountain, the second, the third. Up around the corner and down the bumpy road: no, that wasn’t right. Back to the fork in the road, and to the left: maybe that was right? Around another corner: up a hill, back down a hill. I think that circle thing might just be where we’re supposed to be?

We parked our car and started looking at each of the gravestones.

It was holy, eerie, fully alive. We saw family plots, ethnic plots, gravestones covered with flowers, covered with weeds, covered with grass clippings.

I watched my parents: they walked along the rows, peering down at stones fleshed in soil. The sun was only beginning to come out, but I didn’t know how much longer they could take, how much longer they could stumble up and down the hillside.

“Cara, I don’t think this is the place,” my dad said.

“Yeah, I think we should probably go ask a groundskeeper,” my mom added. I looked at them: if I’d been a betting woman, I would have sworn we were in the right place, but two to one, I’d already been voted off the island.

So, we got back in the car and drove back down the hill. We found a groundskeeper who asked for the section, the plot number. Then we drove back up the hill, past the first fountain, the second, the third. We took a left at the fork, and then another and another, and we parked mere feet away from where we’d been just minutes before.

Betting woman, I tell you.

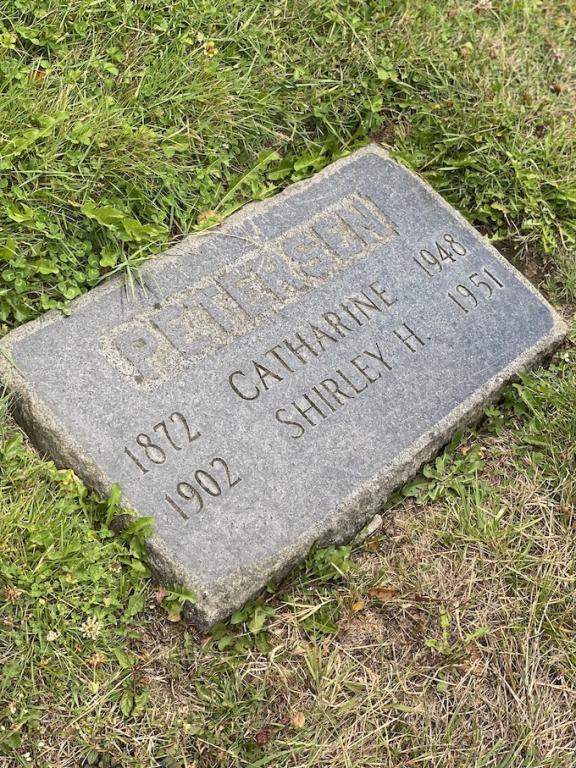

We got out of the car, but this time, we walked farther down the row, all the way to the end of section 66A. The groundskeeper pointed to rows that likely held his tombstone, rows we hadn’t so much as looked at in our first go of it.

All four of us set to looking, but we didn’t find the stone. The groundskeeper went to get his shovel: cemetery groundskeepers are a magical sort that know digging secrets, secrets about plot numbers that exist at the bottom of gravesites, if you just unearth them a tiny little bit.

But then, the groundskeeper called out: “Here! Here he is!” He was back up at the top of the hill, standing next to a gravestone that was nowhere near where we thought my grandfather was supposed to be. He hadn’t had to get his shovel, after all. This wasn’t his first rodeo, but he knew to keep looking, keep watching, keep waiting.

We three trapsed over. We stared at the stone: Catherine Petersen, his mama. Shirley Harry Petersen, him. My mom’s dad. My grandfather. Born: 1902. Died: 1951.

“You know,” my mom said, “I don’t remember what his face looks like anymore. But I remember his feet. I remember what his feet and shoes looked like, because I used to tie his shoes. That’s what I remember.”

We stood at Grandpa Shirley’s gravestone, staring at our own shoes. I thought about his shoes too.

I thought about the things we treasure: the memories, the stories, the tales that touch our souls.

I thought about the man who came to Jesus and said, “Teacher, tell my brother to divide the family inheritance with me.” It’s a question that’s not so hard to imagine happening in our own lives too, but Jesus’ response is far from the words a family attorney might say in return: “Take care! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; for one’s life does not consist in the abundance of possessions.”

Jesus begins to tell a parable, a story about a rich man who grows lots and lots of food, so much food, in fact, that his house is not big enough to store it.

So, he comes up with a brilliant plan: he will tear down his barns and build bigger barns, then he’ll have a place for all those crops, for all that stuff.

And when that happens, he will say to his soul, “Soul, you have ample goods laid up for many years; relax, eat, drink, be merry.”

This response we know, for this is the response we strive after. We deserve it. We’ve earned it. After we work hard, we play hard. After we buy our big house, we fill our big house. We do as we’ve been conditioned to do, if we can.

But God says otherwise: ‘You fool! This very night your life is being demanded of you. And the things you have prepared, whose will they be?’ So it is with those who store up treasures for themselves but are not rich toward God.”

It’s that last line that gets me, that invitation that makes me wonder what it means to be rich toward God – when it’s not about the house or the barns or the vacation homes, and it’s not about the books or the clothes or all that food that fills our pantry, but instead, it’s about bending down and tying your father’s shoes when he can’t tie his own shoes.

It’s about listening and showing compassion. It’s about honoring. It’s about being present, which when you’re a groundskeeper, sometimes means dropping what you’re in the middle of doing and peering down at gravestones with a family in need.

Maybe, when we think about Paul’s letter to the Colossians, it means getting rid of the anger and wrath, the malice and slander and abusive language that comes from our mouths. It means not lying to one another, and instead, clothing ourselves with the clothes of Christ.

It means giving thanks to the Lord, as Psalm 107 says, for this steadfast love that comes straight from heaven down to earth, endures forever.

It means letting the redeemed of the Lord say so, which is to say, to remember and say and believe that we are loved – that you and me, the people inside the walls of this holy place and outside it too, are God’s beloved, and nothing’s going to stop this love.

Maybe that’s what it means to be rich toward God, as God is rich toward us.

Let it be so.

Amen.