The news that 49 people were shot and killed at two different mosques in New Zealand this morning left me baffled, to say the least. Almost as baffling was the statement given by NZ’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern in response to the shooting:

We are a proud nation of more than 200 ethnicities, 160 languages, and amongst said diversity, we share common values and the one we place the currency on right now and tonight is our compassion and the support for the community of those directly affected by this tragedy and secondly, the strongest possibly condemnation of the ideology of the people who did this. You may have chosen us. But we utterly reject and condemn you.

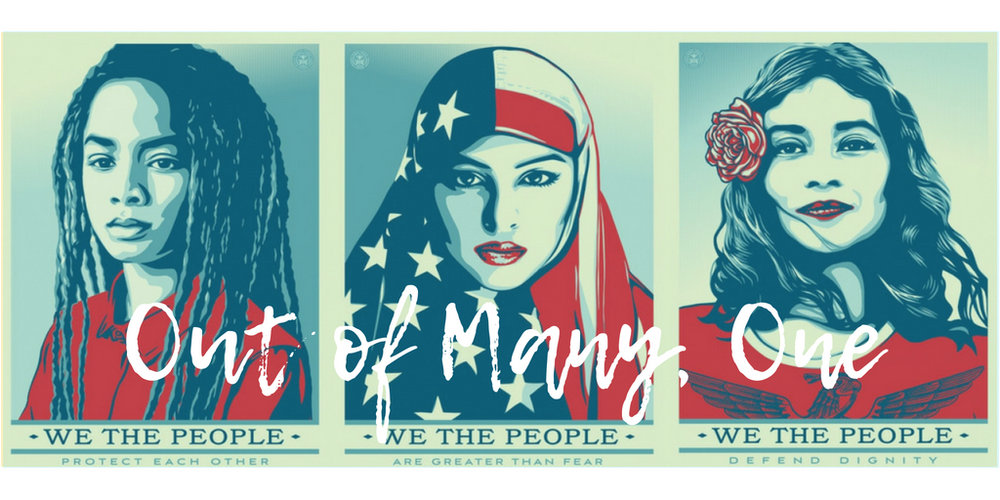

After an act of violence has been perpetrated against a minority group, it has become common place for public figures to condemn the “hateful people” who committed it and to exhort everyone to be more tolerant of said minority group. The cardinal virtue of diversity, and it’s daughter virtue tolerance, are driven by a sincere desire to welcome cultural minorities. But in reality, it reflects a rather naive attitude toward human nature, especially when applied to the presence of religious minorities in a society. Her affirmation of the faceless array of ethnic groups seemed to group Muslim New Zealanders into the mix, as if they weren’t a community with a unique set of values, traditions, and beliefs.

As a high school teacher, I am quite skeptical about this approach. As much as these acts of violence deserve condemnation, I think there is an important anthropological piece missing here. Humans learn to act justly not only through condemnation and exhortation, but through being exposed to the truth. It’s one thing to tell someone that they must tolerate minority groups, but actually teaching them about that group of people, exposing them to their traditions, beliefs, and way of life, can bring a society much further than mere toleration can.

When it comes to ignorance and hatred toward racial minorities, (US) public schools have striven to educate students to recognize the dignity and rights of people of color. I remember starting to learn about the history of slavery and the civil rights movement when I was in first grade, each successive year learning more and more about the history and cultural expressions of Blacks in the US.

As much as racial injustice continues to plague our society, I think it’s fair to say that the incorporation of Black American history into public school curricula has played a role in significantly decreasing expressions of bigotry toward Blacks.

But when it comes to educating people about the history and beliefs of religious minorities (let alone any religious communities), I see little being done by public institutions in secular countries. In all of my years of public schooling, we only spent one month learning about the religions of the world. I barely learned anything about the history and beliefs of the world’ religions, other than that I was supposed to “tolerate” and “be accepting” of them.

If we want to discourage acts of violence toward religious minorities, we need more than to teach toleration. Instead, public schools should be expected to teach the history and beliefs of the world’s major religions.

In secular societies, much of the confusion begins with the reduction of religiosity to a mere “identity category” that’s interchangeable with race, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. But what does it actually mean to identify with a particular religious tradition? I find the writings of Italian theologian Luigi Giussani to be helpful here.

In his book The Religious Sense, Giussani asserts that religious experience emerges from the “set of ultimate questions and desires that constitute the person’s ‘heart.’” The heart, being the center or core of one’s humanity, thirsts for love, justice, beauty, and truth. The heart drives us to look for answers to questions like: why do we exist; why do we die; and what is the ultimate meaning of life?

Each religious tradition offers a path toward discovering the answers to these ultimate needs and questions. One’s religious experience is foundational to her identity. Because it engages the human person’s “ultimate” dimension of existence, and responds to what is most central to who she is, it provides her a framework by which she can make sense of the other, less ultimate, dimensions of her life (ethnicity, nationality, gender, job, etc.).

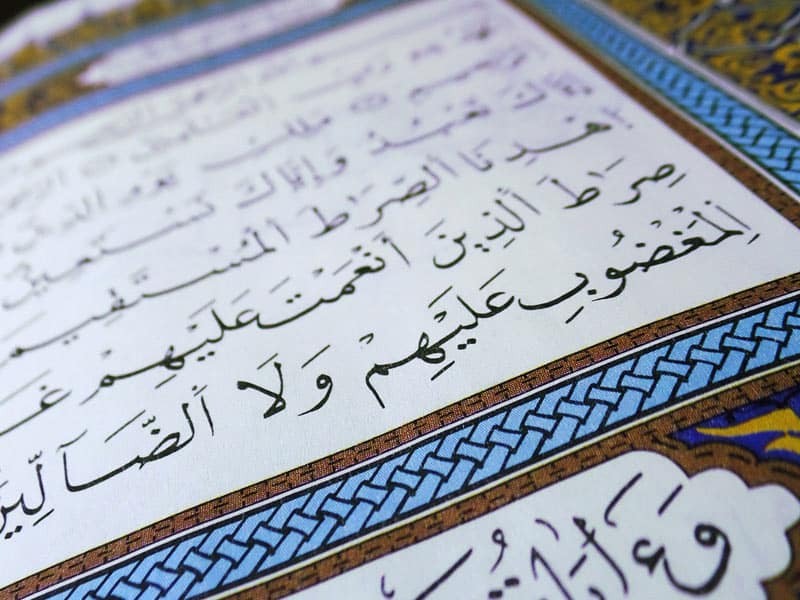

Islam, and all other religious traditions, deserves much more than toleration. It is a rich and complex tradition that colors the multiple facets that make up the daily lives of its adherents, and gives them a sense of ultimate meaning or purpose. Perhaps people would be less likely to hate Islam if they were taught its history and the nuances of its teachings.

A robust curriculum in religious literacy would enable people to recognize the common ground they share with those whose beliefs are different from their own, and would also enable them to have respectful, intelligent debates about the aspects that they do no agree with.

Without this, people will continue to misunderstand religious minorities. Islam will remain either a mere “religion of peace” that is no different from Christianity or atheism, absorbing it into the amorphous set of “common values” that undergird allegedly tolerant societies…or it will be seen as a dangerous religion full of terrorists. A semester’s worth of learning Quranic interpretation throughout history will show that Islam will dispel of any of these reductive conclusions.

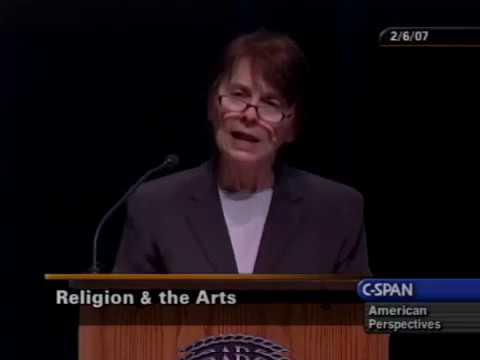

Dr. Camille Paglia argues that exposure to religious traditions is necessary in order to develop a truly multicultural society.

Comparative religion is the true multiculturalism and should be installed as the core curriculum in every undergraduate program…every educated person should be conversant with the sacred texts, rituals, and symbol systems of the great world religions and that true global understanding is impossible without such knowledge.

Paglia goes on to argue that religious literacy can serve as an antidote to the sense of emptiness that many students face today.

Not least, the juxtaposition of historically evolving spiritual codes tutors the young in ethical reasoning and the creation of meaning. Right now, the campus religion remains nihilist…Too many young people arrive at elite colleges and universities with skittish, unformed personalities and shockingly narrow views of human existence, confined to inflammatory and divisive identity politics.

As a teacher of world religions at a Catholic school, the recent events have made me more thankful for the freedom I have to talk to my students about how the world’s religious traditions have helped people make sense of life’s “ultimate questions.” In my class, I encourage my students to go beyond toleration by seeking to understand the sense of meaning that these traditions give their adherents.

This is why I get them to engage each religion on its own terms. For example, I invite a rabbi to speak to them about what it means to him to lead a Jewish congregation…and we go on a field trip to a local mosque to pray with the community during jummah.

I’m also thankful that my school takes its Catholic identity seriously, in the sense that it seeks to be truly “universal” by welcoming a diverse array of students, including Catholics, Protestants, Muslims, Hindus, and atheists. My school allows me not only to tolerate the non-Catholic students, but to pray openly with them and to speak openly with them about their beliefs.

This kind of openness doesn’t seem to be possible in public schools at the moment. In public schools, students’ freedom is ordered not toward an ultimate, universal truth, but toward individual autonomy, authenticity, and self-expression. But if my truth is different from your truth, then I can’t experience a deep sense of love or unity in the truth with you. The best we can do is tolerate other people’s right to believe something different from me.

I’ll close with some words of wisdom from Senator Cory Booker, who warned that tolerance is incapable of sustaining our nation’s growth.

Tolerance says I’m just going to stomach your right to be different, that if you disappear from the face of the Earth, I’m no better or worse off. But love — love knows that every American has worth and value…love recognizes that we need each other, that we as a nation are better together, that when we are divided we are weak, we decline, yet when we are united, we are strong, when we are indivisible, we are invincible.

It’s my hope that my students will leave my class having learned to love people whose religion is different from their own and to respect and understand their beliefs. I also hope that public institutions will begin to promote religious literacy, rather than mere toleration. Until then, I will continue not to be surprised by the ignorance, hatred, and violence directed toward religious minorities.