When engaging with pop culture, Christians seem to respond in three unique ways: to fear, to condescend, or to assimilate. Each of these, while understandable, are ultimately unhelpful with the end goal being the reaching the lost.

Christians have always had a complicated and fraught relationship with pop culture. Through the past decades, we’ve witnessed three distinct responses to the prominent entertainment and art of today, originating from the growing secular culture as Christianity’s influence has waned.

The first and most common response has come from the mainstream evangelical culture, marking itself by a reactionary fear, where Christians have become known for their wary interaction with all things popular, — music, movies, TV shows, and video-games — warning of their corrosive and dangerous effect on society, even going so far as to boycott entire companies and declare pop stars as “demon possessed.”

The next response comes from the educated and elite sects of the church, who have taken a different but equally negative view of secular pop culture, taking issue not as much with objectionable or adult content, but rather popular art’s quality (or lack thereof), opting to look down upon the entertainment of the masses as lower forms of entertainment that they assess to be base, simplistic, and either ignored or written about in condescending tones.

The final response is from a smaller and perhaps newer subset of the church, which I refer to as “the assimilators,” who take the “If you can’t beat them, join them” approach and camouflage themselves with secular pop culture — to the degree that one can often not differentiate between their churches and the most popular nightclubs. They are known for going light on boring theology and heavy on non-problematic, pop-philosophy phrases from popular self-help books, and vying for celebrity attention and cultural approval to utilize as evidence of their relevance and quality.

While I understand the desire and impetus behind each of the responses to pop culture found in different Christian group’s schools of thought, I believe each to be lacking and missing the mark when it comes to addressing popular culture and the beliefs and philosophies that fuel it. I’d like to address each one of these groups and their reactions and offer what I believe to be a more practically beneficial, healthy, and ultimately Christian way to go about engaging with secular pop culture.

Fear Not…

Like any kid growing up in the 90’s, I found myself obsessed with Power Rangers. Something about cool action heroes in brightly-colored costumes using martial arts to defeat robots and monsters appealed to my young mind. The only problem was that some parents in our church informed our family that there was magic in the story lines, and letting kids watch it would not only make them violent, but lead them down a dark path of witchcraft. You can imagine my disappointment when I discovered that the awesome thing all my friends were talking about wasn’t Christian and I wasn’t allowed to watch it.

In the years since my departure from the Power Rangers community, I’ve seen countless instances of Christians quickly making snap judgments about whatever new show, song, video game, or movie is currently spotlighted on the stage of culture. And while I understand the fear, I’ve all too often seen these judgments made on half-truths and based upon a faulty belief that anything secular is inherently corrupt. Because of this more reactionary and fear-based approach, I fear that we are not only cutting ourselves off from a culture we were called to love, shape, and influence, but we are also not offering anything in its place.

The reality is, I was made to be interested in Power Rangers as a kid. It’s a good, healthy, God-created thing for kids to be drawn to heroes and stories of overcoming evil. So when that was taken away from me, there was a void left that was incumbent on the church to fill. But unfortunately, the church had become more practiced at deeming and destroying anything that looked “bad,” but had very little to show when it came to offering something “good” in its place. There were a few attempts with the likes of VeggieTales, Bibleman, and Adventures in Odyssey, but ultimately, the grand majority of Christian’s answers to culture’s entertainment were unappealing, unsatisfactory, and even when they were up to snuff, they were few and far between, as very little value was put on creation of great things.

As a result, the kids who were sheltered from secular pop culture were mostly fine with the church’s guidance up until they left the home and suddenly saw and tasted the more enticing art of the world and found it was more compelling than anything they found during their years sequestered inside the church. Studies show that many in this generation are leaving behind what they find to be the hollow, reactive fears of their families and faith communities, instead gravitating towards the more connective and quality art, and ultimately philosophies, of secular culture.

Judge Not…

A few years back, I was visiting a city that was home to one of the most prestigious universities in the world. I attended a dinner party that was filled with some of the greatest Christian minds and scholars. I learned much and loved the scintillating conversation and intellectual topics. But somewhere in the course of the evening, the conversation took a turn. When asked what projects I was working on, I mentioned that I was writing a book on video games and their artistic and theological value. In response I received a look of sheer disbelief and was told straight out that video games weren’t art and instead were a juvenile and a low form of entertainment meant only for basement-dwelling idiots. I have long been a “gamer,” and while there are games that are base and simple, I have vast experience with beautiful uses of the medium that often brilliantly weave together engrossing narrative, compelling acting performances, beautiful music, and stunning visuals into a moving piece of art. I tried to reason with the intellectual who was so casually dismissing a medium that is now more monetarily successful than the literary, film, and music industries combined (yes, you read that correctly), but my arguments were to no avail against the preconceived notions that live in some more elitist Christian circles about both video games and pop culture in general.

This attitude is nothing new and it’s not sequestered to only Christian circles. We’ve seen many condescending attitudes from more elitist, culture critic groups who look down on those who watch films like The Avengers, or listen to Taylor Swift, or read Twilight. And while I’m glad there are still those who seek to call artists to high standards in their creations, as well as viewers in their consumption, I fear that often the baby is thrown out with the bathwater when we begin with the assumption that pop culture and its art is something we should dismiss, ignore, or look down upon. Whatever our artistic tastes are, art in pop culture is, by definition, the most popular art. It’s the media and entertainment the highest amount of people are connecting to and engaging with. This reality right here should cause us to pause before we judge it too harshly. If we, particularly as Christians, desire to reach the world with our creations, we must first understand them — their loves, likes, hopes, dreams, fears, and desires. The popular entertainment of today can give us an insight into the hearts and minds of today’s culture so that we can go about knowing how to reach those who need to be exposed to the true and the beautiful. To dismiss the chosen “art” of any people, even pop culture, is to dismiss them — which ultimately makes it impossible for us to reach anyone outside of the sequestered clubs we comfortably sit in.

They Will Know You’re My Disciples…

A few years back, my wife and I decided to attend a very popular church in New York City that multiple friends had suggested we attend. The church was held in a large and well-known concert venue in the middle of the city. We arrived early and after having our bags searched and walking through metal detectors, we found our way into the venue — sorry, church — and made our way to the front to find seats. But as we approached the front rows, we saw that the first four rows were roped off. Striking us as odd, we asked a parishioner why this was. We were told very matter-of-factly that the section was reserved for the celebrity attendees who came in through a private entrance. It was hard to not immediately be reminded of the handful of “Hollywood” parties I had attended during my career as an actor, often held at clubs where everyone was split between the VIP section and the non-VIP sections (my section). Eventually the auditorium was filled with thousands of young, extremely hiply-dressed 20- and 30-somethings who looked like they had walked straight out of a fashion show and into church. The worship service was admittedly quality, rivaling the noise level of any of the rock concerts I had attended in my youth. And the sermon, given by a pastor garbed in the skinniest of jeans, a ripped t-shirt, and a pair of sneakers that I later found out were nearly a thousand dollars, was ultimately an inspirational TED Talk about loving ourselves more. The service ended with a slickly-cut video set to dubstep music encouraging sign-ups for their upcoming conference, which was vastly out of our price range.

The experience wasn’t a bad one, but it wasn’t a very spiritual one. I found my attention was less on praising God, learning His ways, or fellowshipping with believers, but instead on the spectacle that seemed to have been created to look and feel like the rest of the world. Looking back, it felt more like a Christian-themed rock concert, TED Talk, and social club than it did a church. And I understand the philosophy behind services and movements like these. They’re built on a belief that to attract and reach culture, the church must essentially become, look like, and assimilate into culture. And it works, for a while. But the problem with this philosophy is that to become and look like culture, we end up having to rid ourselves of aspects of our faith that stand out in contrast to culture, and those aspects are often the ones that people need and are longing for the most.

I now attend a very small church. It’s a liturgical church, which means many of the happenings in the service are rooted in traditions going back thousands of years. Worship service is oftentimes filled with ancient hymns. The rest of the service is filled with readings, kneeling, crossing, sometimes incense, and the clergy are garbed in robes. This service looks absolutely nothing like the rest of my life, and I love that. It reminds me of God and how He is in the midst of us and with us, but isn’t exactly like us. He’s set apart — something He has called us to be as well.

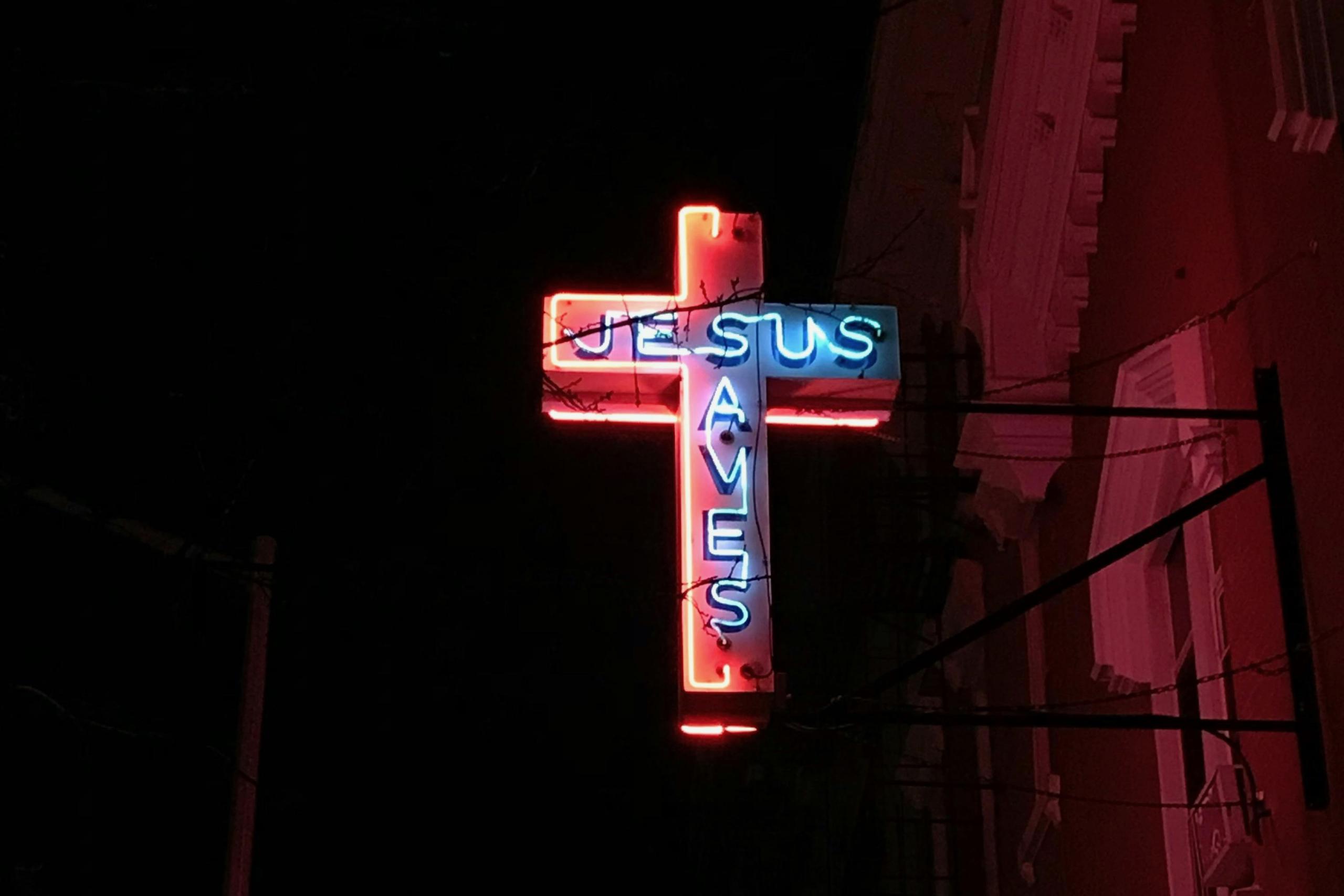

Salt and Light

Jesus called us to be “salt and light,” to bring appetizing beauty and illuminating truth to the world we find ourselves in. But sadly, I think we’ve lost our “saltiness,” and ultimately, our cultural relevance — evidenced by statistics detailing declining church attendance and the rise of the latest generation’s self-identification as “religiously unaffiliated” or “nones.” It’s no wonder Christians have reacted the way they have to these unsettling cultural truths, but it’s also part of why it’s happening. Until we can learn to face the modern secular world without fear or separatism, without condescension or judgment, while at the same time remaining set apart and offering something better than what the world has, we will continue to watch our influence wane.

So as we attempt to be salt and light to a world we’ve been called to reach with the beauty and truth found in our faith, may we not be scared or prideful, and may we always remember that the uniqueness of the gospel has the ability to change the world.